|

||||||||

|

By Victoria Parsons

Around the world, Tampa Bay is earning accolades as one of the few – if not the only – estuaries where seagrasses are rebounding even as populations in adjacent watersheds boom.

Florida’s largest open-water estuary, Tampa Bay is recognized as the comeback kid who battled back from the brink, thanks to the grit and determination of a small but determined group of people and a larger community that recognized its value just in time.

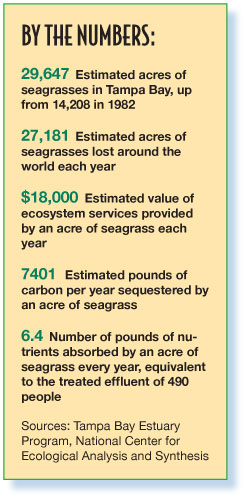

Seagrass beds, the cornerstone of life in an estuary and an important indicator species, now cover more acreage in Tampa Bay than they have at any time since the 1950s. With nearly 30,000 acres of seagrasses growing in the bay, scientists note that the pace of recovery has quickened over the last decade, up to about 510 acres per year, compared to about 427 per year prior to 1999.

But underneath the surface, scientists and bay managers are taking a deeper look at seagrasses and seagrass management to reveal a more complex picture:

- Scientists are re-assessing targets for nitrogen loading and water clarity in some bay segments where seagrasses have failed to grow even though water quality has improved dramatically.

- Some scientists are calling for increased focus on the species of seagrasses growing in the bay. Seagrass typically follows a natural sequence from more ephemeral Shoal grass to Turtle and Manatee grass that is more resilient, but current sampling methods are not precise enough to track the changes over time. That raises the question of how healthy seagrasses really are, if mature beds are being replaced with species that are less resilient.

- That potential trend toward more transient species like Shoal grass may mask other downward movements, particularly in areas that are being damaged by prop scars. Those areas are often covered in mature Turtle grasses but areas scarred by boat propellers are being repopulated with Shoal grass that is likely to die back if conditions change.

- Management actions focused on water quality have been extremely effective over the years, but some scientists are calling for an increased emphasis on physical impacts, such as those caused by boat propellers.

If seagrasses continue to rebound at the rapid pace seen over the past 10 years, it will be 2020 or 2025 before the Tampa Bay Estuary Program meets its 38,000-acre goal that reflects 1950s coverage. If the rate of recovery reverts to the average pace, it could be 2045 before the goal set in 1995 is realized.

This issue, Bay Soundings takes a closer look at seagrasses -- the good, the bad and the rarely discussed – through the eyes of scientists, advocates and seasoned observers.

In Tampa Bay, Seagrasses Define Success

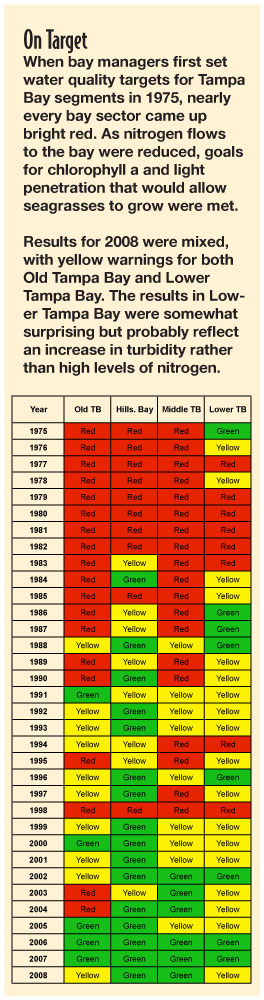

When the Tampa Bay Estuary Program began developing a comprehensive plan to restore Tampa Bay in the early 1990s, bay managers selected seagrasses as the “living resource” that would reflect their success for two reasons:

First, seagrass beds are critical to the health of the bay. Up to 90% of the commercial fish and shellfish depend upon them at some point in their lives, and they form the basis of a food chain that impacts almost every underwater creature. Seagrasses are also considered an indicator species because they are extremely sensitive to declines – or improvements – in water quality. For seagrasses to thrive, the water must be clear enough for light to reach the bottom of the bay.

The key to maintaining water clarity is preventing excess nitrogen from entering the bay. While nitrogen is necessary for plant growth, excess levels fuel the growth of microscopic algae that clouds the water and prevents light from reaching the bottom.

Underlying the plan for restoring Tampa Bay was a theme Kevin Costner fans will recognize: If we clean it, they will come.

Beginning in the 1950s, thousands of acres of seagrass habitat were destroyed with dredge-and-fill development that turned shallow coastal areas into high-and-dry waterfront communities with deep canals. At the same time, the region grew exponentially, with Tampa’s population nearly tripling from just 108,000 in 1940 to nearly 300,000 in 1980.

With growth came pollution that destroyed even more seagrass beds. A wastewater treatment plant opened in the late 1940s at Hookers Point but by 1970, the stench was so bad it was said to tarnish the silver in homes lining Bayshore Boulevard. Seagrass in Hillsborough Bay had virtually disappeared and the bay bottom was covered with six feet of malodorous “glop.”

The turning point came in 1979 with the completion of the Howard W. Curren advanced wastewater treatment plant. With Hillsborough Bay’s major source of nutrients shut down, seagrasses slowly returned. More than 800 acres are now flourishing in what was once the bay’s most polluted segment.

Scientists Turn Focus to Feather Sound

Scientists Turn Focus to Feather Sound

While Hillsborough Bay basks in the spotlight, scientists are turning their attention to a small corner of Old Tampa Bay, just off the highly urbanized Feather Sound community and north of the Howard Frankland Bridge.

Water quality is poorer in that part of the bay, but not so poor as to explain the lack of seagrass regrowth. And while circulation is limited, it’s not enough to account for the patchy response. Looking for a cause has led scientists to study everything from the impact of stingrays foraging in sandy bottoms to the effect of epiphytes, the tiny plants that grow on seagrass blades and may block the light the seagrass needs to survive.

“There’s no clear answer to why seagrasses haven’t recovered in Feather Sound,” notes Lindsay Cross, environmental scientist at the Tampa Bay Estuary Program.

Looking for a cause – and then working toward a cure – has made the Feather Sound area a national model for seagrass research, she adds. “I’m not aware of any other place in the country where so much in-depth research has been conducted.”

More recent research focuses on the most effective way to restore mangroves and marshlands located between the urbanized uplands and shore. Requests for proposals were posted earlier this summer, with funding for the restoration coming from the Pinellas County penny sales tax for community improvement.

Ditches in the generally healthy mangroves, probably dug in the 1950s to minimize mosquito populations, criss-cross the bay’s borders near Feather Sound, allowing stormwater to enter the bay practically untreated, including runoff from golf courses using reclaimed water. Restoring the natural contours would allow water to move more slowly through the system so mangroves can absorb nutrients before they reach the waters of the bay.

“There are about 100 acres of mangroves bordering this part of the bay, but we’ll start small,” Cross notes. “We’ll monitor changes, particularly looking for improvements in seagrasses. We also may see improvements in fish populations when we restore the tidal wetland habitat.”

A second initiative focuses on Lake Tarpon, which connects Tampa Bay via a man-made canal dug in 1967 to prevent flooding. It’s currently the largest source of nitrogen in the Old Tampa Bay segment, contributing more than 100 tons annually. Three alum treatment facilities will treat runoff from nearly 900 acres, reducing nitrogen loadings by approximately 40%, phosphorus by 90% and suspended solids by 95% when complete next year.

The experiences in Feather Sound also highlight the need for bay managers to revisit the targets set in the 1990s, adds Ed Sherwood, TBEP’s senior scientist. “Light attenuation targets might not be ‘one size fits all,’ depending upon what dissipates the light.”

Nitrogen Consortium “Holds the Line”

Much of the success of seagrass regrowth in Tampa Bay can be attributed to a little-known group that has made amazing strides in “holding the line” on nitrogen loadings to the bay even as the region’s population grew by nearly a million people.

The Nitrogen Management Consortium was created in 1996 through the Tampa Bay Estuary Program as a voluntary group of partners including representatives from electric utilities, industry and agriculture along with local governments and regulatory agencies.

Over time, it has evolved into one of the nation’s largest nitrogen allocation groups in response to increased regulations.

The group is nearing completion of a years-long process that allocates nitrogen sources to meet the new state and federal TMDLs – or total maximum daily limits that track the maximum amount of a pollutant that a body of water can receive while still meeting water quality standards. Until recently, the consortium's initiatives have been voluntary, but meeting the new state and federal nitrogen limits will require firm commitments from its partners.

“It’s largely through the consortium’s efforts that we’ve been able to hold the line on nitrogen loadings,” said TBEP’s Sherwood. “Nitrogen loadings are still at 1992-94 levels even as the region’s population has grown because the partners in the consortium have offset that growth.”

Nitrogen in Tampa Bay comes from many sources:

• Stormwater is the largest single source of nitrogen in Tampa Bay, contributing more than 60% of total loadings. Stormwater from residential neighborhoods, which flows across yards and driveways picking up excess fertilizer, petroleum products and even dog poop contains more contaminants than stormwater from intense agriculture or commercial/industrial properties.

• Atmospheric deposition created when electric utilities and automobiles burn fossil fuels that produce oxides of nitrogen. Up to 20% of the nitrogen in Tampa Bay literally falls from the sky either onto the bay or its watershed, where it is carried to the bay in stormwater.

• Wastewater treatment plants that ring the bay once generated many tons of nitrogen but upgrading those facilities was the turning point for Tampa Bay. Today only about 9% of the nitrogen in the bay comes from wastewater.

• Industrial sources including fertilizer plants only emit about 4% of the nitrogen loadings to Tampa Bay.

The Nitrogen Management Consortium has developed a total of 250 projects that reduced nitrogen loadings by 461 tons, ranging from major construction projects to smaller stormwater retrofits and wetlands restoration that filter pollutants naturally.

Protecting Seagrass from Physical Damage

As nitrogen loadings remain steady, bay managers are increasingly focused on physical damage to seagrass beds, particularly the damage caused by boat propellers.

The third time was the charm for supporters working toward protecting seagrasses from prop scars. Legislation approved in the 2009 session details a series of fines for boaters who damage seagrasses in aquatic preserves. Robin Lewis, president of Coastal Resources Group, Inc., a not-for-profit educational and advocacy group, was a major player in the effort that led to its final passage and governor’s approval.

In Tampa Bay, that includes all waters surrounding the entire Pinellas peninsula as well as separate preserves at Boca Ciega, Cockroach Bay and Tierra Ceia.

“It’s not set up to be revenue-generating legislation,” says Kent Smith, FWC administrator specializing in habitat conservation. “The idea is to establish a disincentive for boaters who are causing scarring in seagrass beds.”

Fines begin at $50 for a first offense and escalate to $1000 for a fourth offense in 72 months. The law takes effect on Oct. 1, 2009, but Smith said that the FWC would issue warning tickets for six months to a year. “We need to get the message out to boaters, we’ll post signs at access points and provide brochures for law enforcement officers.”

While some boaters damage seagrass beds accidentally, others intentionally power through shallow waters for better fishing opportunities, not realizing that the damage they cause directly affects fish populations, Smith said. “For every square foot of seagrass they destroy, there are measurably fewer shrimp – which means fewer trout.”

Enforcement will remain a critical issue, since an FWC officer must see the boat creating the damage before he or she can write a ticket, adds Nanette O’Hara, public outreach coordinator for the Tampa Bay Estuary Program.

Questions Remain on Successional Species

In a natural marine environment, seagrass beds typically evolve from Shoal grass that is usually the first species to recolonize an empty area to more resilient Turtle and Manatee grass. As Tampa Bay’s seagrass meadows expand, some scientists are concerned about that natural successional pattern.

“Of those 29,000 acres, how much is healthy, mature seagrass beds with robust species that can resist future changes?” Lewis asks rhetorically.

Using current technology, the question can’t be answered because the aerial photos used to track the extent of seagrasses in Tampa Bay rely upon 1:24,000-scale digital images. “To show emergent species, we’d need much higher resolution -- and more dollars,” notes Kris Kaufman, environmental scientist at the Southwest Florida Water Management District.

A separate transect monitoring program expands on the long-term efforts of Tampa’s Bay Study Group to ground-truth 35 sites in four bay segments and track the extent, health and species of seagrass beds. Sites at Riviera Bay, Venetian Isles and in the Picnic Island area are showing the expected Shoal grass with some areas in transition to Turtle grass, according to Walt Avery who coordinates the monitoring program.

“It’s a learning process,” he says. There are no textbook examples of how seagrasses recover or how fast a recovery should occur, and no one knows how different species react to available sunlight on the bay bottom.

“We’ve just completed some tests at four sites in the bay with intensive water quality measurements and sophisticated tests on how the plant responds,” Avery adds. “There’s a lot more we need to know about how different species react to different levels of sunlight.”

The probability that seagrass beds damaged by boat propellers are moving toward a mix of Shoal and Turtle grasses is another issue that needs to be studied, Lewis said. “We don’t know if mature seagrass beds are being gradually converted to early successional species. If there are a thousand prop scars side by side, we might not have a nice bed of Turtle grass anymore – it could be all Shoal grass.”

Shoal grass is much more likely to be damaged or killed when the years-long drought ends and stormwater to the bay increases, he adds. “We’ve seen it before – we get new seagrasses, then heavy rains and very large areas of loss. Shoal grass is easily damaged by pollution and salinity changes – Manatee and Turtle grass resist those changes better.”

BASIS 5 to Focus on Future

When the first Bay Area Scientific Information Symposium was called to order in May 1982, Tampa Bay was a different place. Advanced wastewater treatment had begun four years earlier, but massive algal blooms still blanketed Hillsborough Bay during warm summer months and the bay bottom was still barren. Scientists were hopeful that seagrasses would rebound but beds of Manatee grass were still disappearing.

When the first Bay Area Scientific Information Symposium was called to order in May 1982, Tampa Bay was a different place. Advanced wastewater treatment had begun four years earlier, but massive algal blooms still blanketed Hillsborough Bay during warm summer months and the bay bottom was still barren. Scientists were hopeful that seagrasses would rebound but beds of Manatee grass were still disappearing.

Scientists attending BASIS 5, to be held Oct. 20-23 at the Holiday Inn SunSpree Resort in St. Petersburg, will revisit that seminal event to review and update the scientific knowledge presented then. The theme of BASIS 5 is “Using Our Knowledge To Shape Our Future.” Topics to be covered include:

• Geology

• Hydrology

• Water Quality/Primary Productivity

• Wildlife Resources

• Sustainability

• Habitats - Sediments, Seagrass Resources and Emergent Wetlands

• Environmental Regulation & Protection

• Integrated Assessments

• Watershed Management Initiatives

• Anthropology

• Science Communication

• Climate Change

• Future Challenges

Various registration options will be offered with total costs not to exceed $75 for the 3.5-day event and a one-day registration fee option of $35. For sponsorship opportunities, contact Wren Krahl, Tampa Bay Regional Planning Council, at 727-570-5151 ext. 22 or e-mail wren@tbrpc.org.

Tampa Bay Bucks Global Trend

Although loss of seagrass habitat is accelerating around the world, Tampa Bay and other Florida estuaries are bucking the trend. A report published in the July issue of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences notes that seagrasses have been disappearing at a rate of 27,181 acres per year globally since 1980 and that the rate of loss is accelerating.

The 50% reduction in Tampa Bay’s point source nitrogen loadings – and corresponding improvement in water clarity – is cited in the article as an example of how improved management practices can reverse the international trend toward seagrass losses.

Other estuaries in Florida, including Florida Bay and Indian River Lagoon, also have seen increases in seagrass habitats as nutrient loadings dropped.

Billed as the first comprehensive global assessment of seagrass losses, the study found 58% of seagrass meadows are declining and the rate of annual loss has accelerated from about 1% per year before 1940 to 7% annually since 1990. "Globally, we lose a seagrass meadow the size of a soccer field every thirty minutes," said co-author William Dennison of the University of Maryland.

"Seagrasses are disappearing because they live in the same kind of environments that attract people," said James Fourqurean, a professor at Florida International University and a co-author of the study. Nearly half of the world's population lives on 5% of the land adjacent to coasts.

In the Next Issue of Bay Soundings:

The Billion-Dollar Questions

Seagrasses can be transplanted successfully – but it can cost up to $400,000 per acre. It’s clear that we can’t transplant our way to achieving the 10,000-acre increase bay managers have set as their goal, but we’ll take a look at what works and when it’s important to make that investment.

The years-long drought that dried up freshwater wetlands has been good for Tampa Bay because less rain means less stormwater flows into the bay bearing harmful nutrients and other contaminants. New rules that limit both the quantity and quality of stormwater leaving commercial developments and neighborhoods promise to minimize the impact of new construction. Cities and counties also are charged with cleaning up their stormwater – but that’s likely to be an expensive process. Annual maintenance costs for running the alum treatment facility to protect Lake Seminole top $500,000, not including the costs of cleaning up the lake and constructing the facility.

We’ll take a look at what’s been done and what’s on the drawing boards to clean up stormwater in the Tampa Bay watershed.

Seagrasses dubbed “Nurseries of the Sea”

Often called the “nursery of the sea,” a healthy seagrass meadow is more productive than a fertilized corn field. Seagrasses provide food and shelter for an amazing number of creatures, ranging from microscopic epiphytes that live on leaf blades to the larva of nearly 90% of valuable fish and shellfish, and are a food source for sea turtles and manatees.

Often called the “nursery of the sea,” a healthy seagrass meadow is more productive than a fertilized corn field. Seagrasses provide food and shelter for an amazing number of creatures, ranging from microscopic epiphytes that live on leaf blades to the larva of nearly 90% of valuable fish and shellfish, and are a food source for sea turtles and manatees.

They also form the basis of a complex underwater food web, with dozens of species of algae living on their leaf blades and within their root mass. That concentrated food source attracts small marine animals including larval fish and shellfish that feed on the algae and seagrass detritus. Larger predatory fish are attracted by the smaller fish. In fact, some studies indicate that up to 100 times more animals inhabit seagrass meadows than adjacent sandy bottom.

Seagrasses are actually more related to lilies than grasses. They evolved from land plants dating back to the time when dinosaurs roamed the earth. Seagrasses flower underwater, releasing pollen and developing viable seeds that colonize new underwater meadows when conditions are right. Seagrasses also spread across the bay bottom with rhizomes or underground roots that sprout new growth at nodes, much like land-lubber grass in lawns.

As the descendants of land plants, seagrasses require light to survive and they die back if water clouded with algae or other substances prevents light from reaching them on the bay bottom.

Although there are 60 species of seagrasses found in shallow waters around the world, six species are found in Tampa Bay with three species dominating local ecosystems:

Shoal Grass, or Halodule wrightii, occurs in the shallower portions of the bay, landward of the larger seagrass species, Turtle grass and Manatee grass. It is the first to colonize disturbed areas, typically followed in a natural succession to Turtle grass and Manatee grass over time. In some locations, it is considered an “ephemeral” seagrass because it comes and goes from year to year. In other locations it is a perennial species, lasting as a seagrass meadow in shallow water from year to year.

It tolerates a wide range of salinities from river mouths to Lower Tampa Bay where it may be exposed to high levels of wave energy. Shoal grass grows to about six inches tall and has very shallow roots. Its flat, narrow blades have notched tips.

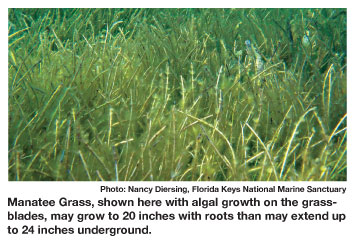

Manatee Grass, or Syringodium filiforme, is generally found growing with other species of seagrasses or alone in small patches, usually in calmer, inland sections of the bay. Its blades may grow to 20 inches with roots that may extend up to 24 inches underground. Unlike Shoal and Turtle grass, Manatee grass blades are cylindrical with two to four blades rising from each rhizome node. It is the second-most common seagrass in Florida waters and, as its name implies, a favorite food of the manatee.

Turtle Grass, or Thalassia testudinum, was once the most common seagrass in Tampa Bay but has been replaced by Shoal grass in many places following extensive damage by boat propellers and ongoing water quality problems. As these stresses are relieved, many of the existing Shoal grass beds could be expected to naturally change to Turtle grass beds through succession. This is happening today along the MacDill Air Force Base shoreline.

Its blades are flat and ribbon-like, growing up to 14 inches long and 1.2 inches wide from rhizomes that may be as deep as 10 inches below the surface. It typically hosts large colonies of epiphytes and its common name reflects its status as a preferred food source for sea Turtles.

Healthy Seagrasses Boost

Scallop Populations

With seagrasses rebounding to levels not seen in 60 years, participants in the 16th annual Great Bay Scallop Search can expect to find more scallops than ever.

With seagrasses rebounding to levels not seen in 60 years, participants in the 16th annual Great Bay Scallop Search can expect to find more scallops than ever.

“Like many fish and shellfish, scallops depend upon healthy seagrass beds for their survival,” says Peter Clark, executive director of Tampa Bay Watch. “We can track the health of the bay by counting the number of scallops we find each year. We hope the number of scallops found increases, which means that water quality and habitat are also improving.”

Last year’s record-setting count of 624 scallops is a promising sign attributed to 25 years of water quality improvements and habitat restoration efforts in our region. Another important point: out of 70 blocks surveyed in Boca Ciega Bay, 33 contained scallops. “This coverage indicates that water quality to support scallops is improving,” according to Kevin Misiewicz, environmental specialist with Tampa Bay Watch. “All indicators point to a phenomenal year for scallops in Tampa Bay in 2009.”

The bay scallop (Argopecten irradians) is a member of the shellfish family known as bivalves. Scallops, which grow to about two inches in size, spend most of their short 12- to 18-month life hiding in seagrass beds. The delicious scallop meat so prized by seafood lovers is actually the scallop's adductor muscle, which it uses to close its shell. Tiny blue eyes along the rim of the shell detect movement and serve as an early warning system.

The bay scallop (Argopecten irradians) is a member of the shellfish family known as bivalves. Scallops, which grow to about two inches in size, spend most of their short 12- to 18-month life hiding in seagrass beds. The delicious scallop meat so prized by seafood lovers is actually the scallop's adductor muscle, which it uses to close its shell. Tiny blue eyes along the rim of the shell detect movement and serve as an early warning system.

As filter feeders, scallops are highly sensitive to the health of the bay and can be used to measure an ecosystem’s health and signal changes in water quality. They virtually disappeared from Tampa Bay in the 1960s due to commercial harvesting, poor water quality and loss of seagrass habitat. Since implementation of the Clean Water Act in 1970, water quality conditions have gradually improved in the bay and scallops are making a tentative comeback in Tampa Bay waters.

Along with serving as an important water quality indicator, scallops can filter as much as 15.5 quarts of water per hour – improving water quality and resulting in long term growth of seagrass beds.

Tampa Bay Watch, Mote Marine Laboratory and the Florida Fish and Wildlife Research Institute are working to increase the bay scallops by raising scallops in laboratories and releasing the juveniles into the bay. It is still illegal to harvest scallops in Tampa Bay.

Turtle Grass (shown below and on headline) has blades that are flat and ribbon-like, growing up to 14 inches long and 1.2 inches wide from rhizomes that may be as deep as 10 inches below the surface.

Photo: Paige Gill, Florida Keys National

Marine Sanctuary