|

||||||||

|

The Road Not Taken:

The History of the Sunshine Skyway Bridge

By Charlie Hunsicker and Allan Horton

By Charlie Hunsicker and Allan Horton

The forces that shape a road often change the landscape in ways not readily visible from an automobile. The Sunshine Skyway and the Interstate-275 superhighway it lifts across Tampa Bay reflect compromises that resulted from the push and pull of such competitive tensions as economics and politics.

This story, gleaned from the factual record, describes how “The Road Not Taken,” as designed by a prominent Florida engineer and native Manatee Countian, could have changed the Skyway and the communities it links.

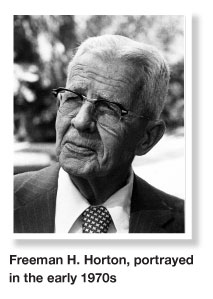

Freeman H. Horton was a seasoned civil engineer when he helped propose in 1945 a bridge across Tampa Bay to Palmetto.

Horton was born August 13, 1897, in Fogartyville, a west Bradenton community with little more than a cemetery remaining to mark its history. He grew up in and on the Manatee River, learning to swim, fish and sail while helping support a widowed mother and his three older step-siblings – two boys and a girl. His engineering prowess earned him early fame at age 11 when the Bradenton constabulary admonished him for sailing his mother’s wagon, rigged with a bedsheet sprit-sail, along Manatee Avenue, stampeding two horse-drawn buggies.

Horton was born August 13, 1897, in Fogartyville, a west Bradenton community with little more than a cemetery remaining to mark its history. He grew up in and on the Manatee River, learning to swim, fish and sail while helping support a widowed mother and his three older step-siblings – two boys and a girl. His engineering prowess earned him early fame at age 11 when the Bradenton constabulary admonished him for sailing his mother’s wagon, rigged with a bedsheet sprit-sail, along Manatee Avenue, stampeding two horse-drawn buggies.

Horton became the first Manatee County High School student to graduate in civil engineering from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Harvard University, in 1918. Following graduation, Horton and his new bride, Mabel Morrow of Bradenton, moved to Cincinnati, Ohio, where he designed highway and railroad bridges and other structures for the Cincinnati Union Terminal Co., including the Mill Creek viaduct and the Union Station dome. He also designed the double-track, Strauss-type, counter-weighted, trunnion bascule bridge over the St. Johns River in Jacksonville for the Florida East Coast Railway, completed in 1925.

As the Great Depression curtailed engineering work, Horton moved his family to Snead Island to operate a truck farm on property he and his wife had purchased in 1924. The family occupied a house on the Portavant Amerindian temple mound and raised squash, cucumbers, Bell peppers, avocadoes and mangos as Horton worked in Bradenton as a consulting engineer.

His projects during this time included Tampa’s Bayshore Drive seawall and boulevard and the Bay Street and Marjorie Park yacht basins.

In response to a federal mandate restricting World War II defense department engineering bids to “architect-engineers,” Horton formed a partnership with the Frank W. Bail Co., Inc., architects and planners, with offices in Bradenton and Ft. Myers. As the principal design and structural engineer in the firm, Horton designed numerous Army Air Corps training fields throughout Florida, the Mayport Naval Base near Jacksonville and numerous other defense and military installations.

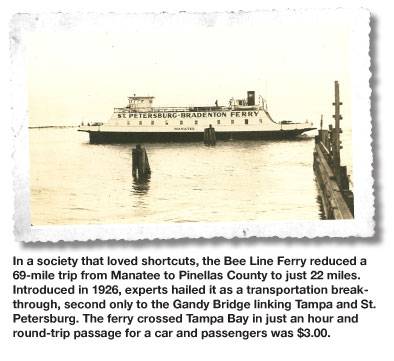

In 1942, the privately owned Bee Line Ferry, Inc. - operating three vessels from Pinellas Point in southeastern St. Petersburg to Piney Point near present-day Port Manatee – ceased operations after the federal government requisitioned its boats for the war effort. As a result, automobiles and trucks had to detour 50 miles inland via the Gandy Bridge.

There also was growing awareness that following the war, growth would explode as the economy rebounded and war veterans, many of whom had trained at Florida bases, returned.

Anticipating the engineering work such post-war growth undoubtedly would trigger, Bail, Horton & Associates formed a joint venture with consulting engineers Parsons, Brinckerhoff, Hogan & MacDonald of New York. On Dec. 20, 1944, the joint venture firms signed a design contract with the St. Petersburg Port Authority, which had acquired the Piney Point Ferry line and its Pinellas and Manatee County properties. In November 1945, the partnership published a detailed report proposing a bridge and causeway facility across Tampa Bay. Its preferred route, estimated to cost “about $8,000,000,” landed the southern terminus of the new bridge and highway system on eastern Snead Island roughly opposite today’s Bradenton Yacht Club.

From that point, the project proposed widening Tenth Street West in Palmetto as a major thoroughfare intersecting U. S. Highways 41 and 301.

History cited by the report reflects urban and traffic conditions almost unimaginable to a contemporary user of the Sunshine Skyway. The ferries linking Manatee County to Pinellas County often were hampered by bad weather and rough seas and routinely operated only in daylight. Although, in its final operating year, the Bee Line Ferry carried 99,000 vehicles and had gross revenues in excess of $170,000, the report estimated those data did not “nearly represent the volume of traffic” which would use a safe facility available 24 hours a day. It estimated its project’s first year’s gross earnings at $825,000 and projected a “peak traffic” count of 4,000 cars daily.

The design team dismissed a tunnel from the outset, focusing its attention on six alternative bridge-and-causeway options.

The design team dismissed a tunnel from the outset, focusing its attention on six alternative bridge-and-causeway options.

The northernmost route, designated “A,” linked Piney Point in Manatee County to U.S. Highway 19 via a landing at Colony Point in southern Pinellas County. Five alternate alignments and facilities were described, but rejected in favor of the preferred route identified as “D,” which connected southern Pinellas County at Maximo Point to Palmetto via McGill Island and Snead Island.

Deemed the most feasible, if not the shortest route across the bay, the Maximo Point to Snead Island proposal crossed four navigational channels – the Boca Ciega, Bunce’s Pass and Terra Ceia Bay channels and, of course, the Tampa Bay ship channel. The preferred “D” design required seven bridges with over-water spans ranging from 250 feet to 12,176 feet in length, linked by dredged-fill causeways. Bail, Horton & Associates was awarded the design contract based on the 1945 proposal, but inability to secure $10 million in revenue bonds forced the state to withdraw its construction plans in the late 1940s. In the early 1950s, the state reactivated the design competition, ultimately awarding the design to the Parsons, Brinckerhoff firm along an amended route. That change shifted the Snead Island landfall to Terra Ceia property owned by Judge H. V. Knott, a former Florida State Treasurer.

Today’s cable-stayed suspension bridge – a replacement for the Skyway span demolished May 9, 1980 by the errant freighter Summit Venture - transports in excess of 50,000 vehicles daily across southern Tampa Bay.

It thus validates the need predicted by Freeman Horton and his partners for a facility directly linking the Pinellas peninsula to southwestern coastal communities. One can only speculate, however, how Horton’s preferred design – the “Road Not Taken” - might have changed forever those communities.

Certainly the landfall on Snead Island linked to Highways 41 and 301 would have split permanently the City of Palmetto along Tenth Street into “north” and “south” communities. It is no stretch of the imagination to speculate that zoning changes would have installed intensive commercial uses along the new, “improved” thoroughfare.

Further south, it is reasonable to assume that the future alignments of Interstate-75 in central and southern Manatee County, and in Sarasota County, might have more closely followed the coastal highways. As a result, development of eastern Manatee County communities, such as Lakewood Ranch, might have been delayed or forestalled significantly.

Finally, one of Freeman and Mabel Horton’s richest legacies, realized in the early 1990s with state acquisition of the land that forms Emerson Point Park, might never have happened.

Managed since 1996 by Manatee County, the park preserves forever the Amerindian Portavant ceremonial mound; a rare, mature hardwood coastal hammock; and a fringing mangrove ecosystem that buffers the park from hurricane erosion forces while providing shelter to the estuarine environments of the Manatee River and Tampa Bay.

Thus the unintended consequences of “The Road Not Taken” may well have proved more beneficial than the initial design for the Sunshine Skyway envisioned by Freeman Horton and his partners.

Charlie Hunsicker is Director of Natural Resources for Manatee County. Allan Horton is a retired journalist and son of Freeman Horton.