|

||||||||

By Victoria Parsons

Sometimes, the best-laid plans turn out even better than anyone involved would ever have expected.

For instance, nobody envisioned that the spoil islands created when shipping channels were dredged across shallow bay bottom would become internationally important bird nesting sites. And the grand plan certainly didn't extend to protecting the vast majority of Tampa Bay's eastern shore in a nearly contiguous corridor.

In fact, the initial plans for Tampa Bay bear little resemblance to the natural beauty we see today. Allen Burdett joined the Florida Department of Environmental Regulation (then the Florida Board on Conservation) in 1968 to enforce development permits in a territory that ranged from Marco Island to Crystal River.

"It was the wild, wild west back then," he recalls. "Some people thought that the whole shoreline should be developed anywhere the water was too shallow to navigate."

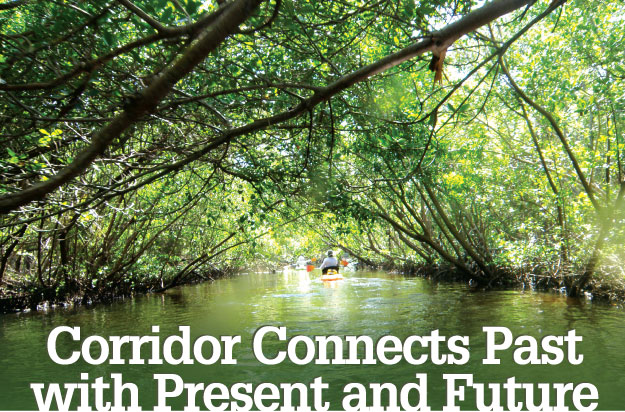

The corridor began to come together about 30 years ago when scientists realized that the accidentally created coastal islands were attracting a wide variety of nesting birds. "We had brand-new research documenting that birds like the white ibis needed freshwater food sources for their young," recalls Robin Lewis, a long-time bay advocate. "Some of them had to fly 30 to 40 miles to find freshwater food."

That led to one of the nation's first referendums where citizens voted to tax themselves to purchase wildlife habitat at Cockroach Bay. "There were some skeptics at first but we put together a good case that we needed to buy and protect this land in perpetuity," notes Rob Heath, former director of Hillsborough County's land management program.

By 1985, more new research detailed the link between mangroves, marshes and fish populations. "That brought a whole new group to the table supporting restoration," Lewis said. "People love birds and even more people love fish. When we could tell them that healthy habitat equals healthy fisheries, we got their support too."

In 1987, 71% of Hillsborough County voters supported a 0.25 mill tax for four years specifically to purchase wildlife habitat in a program called Environmental Lands Acquisition and Protection( ELAPP). "That was one of the first instances of citizens voting to tax themselves for general habitat purchases," Lewis recalled.

By then, scientists had begun to document the value of a corridor, notes Brandt Henningsen, the chief environmental scientist for the Southwest Florida Water Management District who has been involved with many of the eastern shore projects. "The original purchases were happenstance but looking at land acquisitions from a corridor perspective gave us an even longer-term vision," he said. "We began to focus on the connectivity that wildlife needs to thrive."

Much of the corridor, including key tracts at Cockroach Bay, the Rock Ponds and Wolf Branch Creek, was purchased with funding from partnerships created between ELAPP and the water management district. The SWIM (Surface Water Improvement and Management) program led restoration efforts at most of the large tracts along the bay.

When the original ELAPP neared expiration, 79% of citizens voted to continue the special tax levy. "Voters clearly recognize the value of environmental lands purchases," said Jan Platt, a former county commissioner who was a driving force in protecting Tampa Bay. "ELAPP won the biggest majority on the entire ballot that year — even in a difficult economy."

While much of the corridor is already in public hands, the future is less clear for remaining pieces. Land acquisition funding at the state and district level has dried up but Hillsborough County has been able to make several major purchases — in large part because no other entity had cash available when a motivated owner was ready to sell.

"It's good because we may be the only buyer in the market and we have cash available," says Forest Turbiville, section manager for Hillsborough's park department. "It's bad because we've been able to partner with the state or district on over three-quarters of the 60,000 acres we've purchased and that funding isn't there any longer."

Since voters approved spending up to $200 million in 2008, Hillsborough County has made two significant purchases inland but none on the coast, Turbiville said. "We're looking at a piece of land adjacent to 'The Kitchen' (south of the Alafia River and north of Apollo Beach) but we don't know if they'll accept our offer or not."

By law, ELAPP can't pay more than the appraised market value for a piece of property – but appraisals have dropped dramatically too. "We've been very blessed," Turbiville said. "We're one of only about 15 other counties with environmental lands purchase programs. I think we'll come out of this with even more of natural Hillsborough County protected."

For a bird-eye view of the corridor, click here.