|

||||||||

Grow Your Own

Grow Your Own

Eco-Friendly Produce

By Victoria Parsons

At a time when the average vegetable travels 1,500 miles from plant to plate, John Starnes grows most of his own food. Instead of surrounding his south Tampa home with the typical shrubs and lawn, he harvests bountiful tomatoes, greens, herbs and fruit year-round.

Living off the land on a relative small sandy Tampa Bay plot isn’t as easy as farming in rich soil, he admits, but it’s clearly not impossible. And he doesn’t use chemical fertilizers or toxic pesticides on the food he grows, making his fruits and vegetables eco-friendly alternatives to grocery store produce.

The trick, he says, is knowing what to plant when – and preparing the soil first.

While every organic gardener has his or her own tricks (usually involving truckloads of mulch complemented with horse or chicken manure), Starnes recommends using materials that are fast, easy and accessible even for urban gardeners.

First, find a sunny plot, checking to make sure that it will stay sunny year-round even as the sun moves north and south. For each 10-by-10-foot area, purchase one 50-pound bag of cheap dry food dog nuggets, five 20-pound bags of unscented clay cat litter, a 50-pound bag of alfalfa pellets and two bales of coastal hay.

“You can pick up cheap dog food and kitty litter at the grocery store and the alfalfa and hay at a local feed store,” Starnes said. “Most people are surprised at how many feed stores are located in urban areas – just Google ‘feed store’ and your zip code or check the yellow pages to find one near you.”

Spread the first three ingredients evenly over the plot, turn the soil, water deeply, then cover the area with a single continuous layer of flattened cardboard boxes overlapped six inches at the edges, then cover that with the hay, and water again. Let this “ripen” for 2-3 weeks.

As it breaks down, the dog food slowly releases the nutrients and minerals plants need to thrive. Proteins and carbohydrates provide food for earthworms and beneficial bacteria that eventually transform even Florida sand into fruitful soil. The cat litter decomposes into potassium-rich clay that holds water and encourages lush growth. Alfalfa pellets break down into nitrogen and trace minerals, and organic matter that encourages beneficial bacteria. Covering that layer with overlapped cardboard boxes and then the hay chokes out weeds.

“Make sure it’s coastal hay, which is seed-free Bermudagrass and not something that is full of seeds like wheat straw.” he notes. If it’s available, free mulch from a tree-trimming service or a heavy layer of oak leaves can be used instead of the hay, but avoid the use of cypress mulch.

“They’re cutting down trees and destroying wetlands to get cypress mulch,” he said.

If you’ve had a garden before in the spot you’re working on now, or you’re planting over flower beds, water well every week for two to four weeks, then use your hands to pull the hay back, as if you were parting hair, to expose ten 4-inch-wide bands of the damp soft cardboard. Cut ten slits in it to plant seeds or seedlings in the now-rich soil below. This allows for ten rows of veggies.

If you’re planting over lawn or weedy areas, however, you’ll need to wait a minimum of three months for the lawn and weeds to fully die back. “But even if you’re starting from scratch, you can have one very bountiful winter garden planted before it gets hot again.”

Right Plant, Right Time

It’s hard to believe unless you’ve lived in Florida for a couple of years, but the best time for vegetable gardens here is October through March. Temperatures are cooler and the humidity is lower, so outbreaks of pests and fungus are much less likely. Summer crops get planted April through June.

“My favorite winter crops are the brassicas – which include plants like broccoli, arugula, bok choy and mustard greens -- and root crops like carrots, beets and scallions, plus snow and sugar snap peas.” Starnes plants three succession crops between October and early March for steady production. The brassicas, lettuce, sugar snap peas and root crops are both frost-tolerant and easy confidence builders, he adds. “It’s hard to go wrong with the brassicas, even exotic ones like mizuna and arugula that are expensive in grocery stores thrive in Florida winters.”

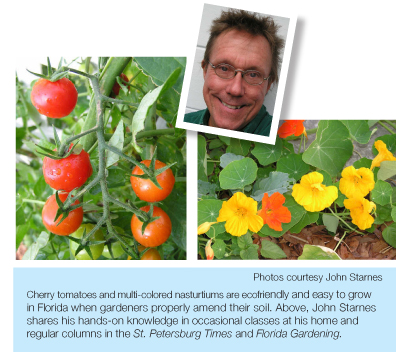

The 10-by-10-foot plot he recommends can grow 10 rows of food, “more than enough to feed the average family of four.” Anchoring each of the four corners of the plot with one tomato plant like ‘Sweet 100’ or ‘Big Boy’ gives gardeners an alternative to the cardboard-flavored grocery store varieties. Another favorite treat is a row of nasturtiums (he recommends the ‘Dwarf Jewel’ mix) to make both the garden and your salads even more colorful and tasty. Or plant them all around the garden as a colorful edible border.

While every brassica will grow in Florida in winter, they fail in in the heat and humidity of summer months. Sucessful summer gardens feature completely different plants that like the humid heat, such as okra, eggplant and sweet potatoes, plus “exotic” tropical food crops he collects like chaya and vigna.

John Starnes, a St. Petersburg Times and Florida Gardening columnist who was born in Key West, opens his garden to classes on an irregular schedule on weekends during the Fall and Winter. For more information, email him at johnastarnes@msn.com or call 813-839-0881. For recommended varieties of summer vegetables, visit the University of Florida’s Extension Service at http://www.ifas.ufl.edu/.

Non-toxic Tricks Protect Plants from Pests

While Florida gardeners often regal their friends from the north with tales of voracious insects that destroy entire gardens practically overnight, Starnes has a handful of natural and non-toxic tricks up his sleeve to prevent insects from eating your dinner.

The first and most important tip is feeding the soil, because healthy plants are less likely to attract damaging levels of insects. Feeding plants with chemical fertilizers, particularly those high in nitrogen, is not a good choice because too many nutrients cause bursts of growth that attract aphids and caterpillars.

Snails and slugs are less common in winter gardens than in the summer. They can be controlled by trapping them in husks of melon shells placed upside down on the ground or stale bread under wooden boards. If there are too many to trap, he recommends a product called Escar-GO! made with iron phosphate and bran and available online.

Caterpillars, including the larva of the imported cabbage white butterfly, may be a problem with the brassicas. They’re easily treated, however, with a natural bacteria called Bacillus thuringiensis (BT) that kills caterpillars but doesn’t affect anything else. “Be sure to use the powdered version, not the liquid kind which contains petroleum byproducts,” he notes.

Other insects, including pests like aphids and whitefly and spider mites, are seldom a major issue in gardens growing in healthy soil. He recommends a hot pepper spray for the occasional problem, made with a cup of pepper flakes (cheap in Asian markets) in a gallon of boiling water seeped overnight, then strained. Add a cup or two of the concentrate to a gallon of water, then a tablespoon of dish detergent (not Dawn, though, it can burn plants) and spray affected areas. Be sure to stay upwind, though, because the spray may burn skin.

His favorite trick, though, is to just blast insects off plants with a coarse sharp spray of water weekly.