|

||||||||

By Matthew Cimitile

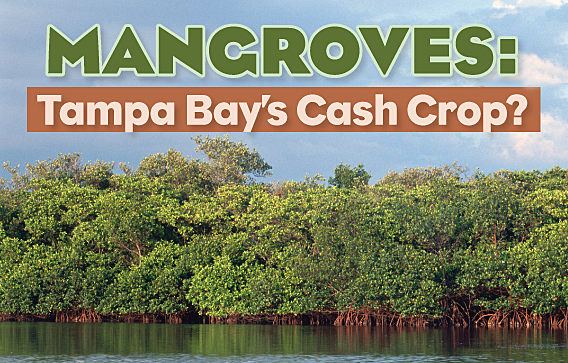

Could mangroves be Tampa Bay's next cash crop?

Obviously, no one is recommending cutting down mangroves to sell, but environmental managers are working toward putting a price tag on the benefits they provide to help ensure that they are protected. Though the process is just beginning here, estimates from studies in other locations indicate that the 15,000 acres of mangrove forests surrounding Tampa Bay could be worth $75 to $225 million a year for the services they provide.

“Measuring the value of these ecological services draws people’s attention to their magnitude and makes it apparent what these assets are worth so we are not making decisions blindly,” says Robert Costanza, University of Vermont professor and a pioneer in the field of ecological economics. He’s leading the national drive that focuses on new ways of assessing environmental resources to move society into value systems that recognize the inherent costs and benefits of ecological services.

Tampa Bay is one of four pilot projects selected by the Environmental Protection Agency for intense research into the value of the region’s natural resources – including mangroves — specifically to quantify the economic and ecological benefits each provides.

“The goal is to elevate ecological decisions to the same level as economic decisions,” says Jim Harvey, a research biologist with the EPA. “We don’t have the framework now for decision makers to look at ecological services the way they would the number of jobs or dollars a development brings to a city or county. Once we can provide them with information about ecological services, they’ll know what it’s worth to save at least a barrier strip of mangroves for storm protection, for instance.”

Katrina Highlights Value of Wetlands

Katrina Highlights Value of Wetlands

While scientists recognize the value of mangrove swamps and marshlands for habitat, nutrient cycling and water filtration, the coastal devastation caused by Hurricane Katrina highlighted the risks and vulnerabilities associated with wetland loss to a more general audience. In response to these significant losses, Costanza worked with colleagues to quantify the protective value U.S. coastal wetlands provide during hurricanes. Using data that tracks damages from past storms and the shrinking wetlands surrounding developed areas, Costanza estimated the storm-protection value of Florida’s coastal wetlands at $3,190 per acre annually.

That may be just the tip of the tree’s overall value because it doesn’t include the habitat’s importance to fisheries. According to a report from the Scripps Institution of Oceanography in California that measured fishing records at 13 mangrove sites in the Gulf of California, income derived from fishing in those areas was worth about $15,000 per acre per year.

And as researchers delve deeper into the value of mangrove forests and natural wetlands, that annual impact is likely to rise when dollar signs can be attached to benefits like capturing sediments and filtering stormwater.

“Beyond the benefits to a wide variety of wildlife, mangroves uptake nutrients from the water column or sediments,” notes Kelli Hammer Levi, program coordinator for Pinellas County’s Environmental Management Department.

Although researchers have not been able to quantify the ability of mangroves to capture nutrients in storm or wastewater, it clearly has some impact, Levi said. “Pinellas County is spending millions of dollars to construct stormwater treatment facilities that capture those nutrients, then hundreds of thousands of dollars a year to run them.”

Finding the Right Price

Costanza is one of the first researchers to place a monetary value on the world’s ecological services and natural capital. In 1997, he combined studies of an individual’s willingness to pay for such ecosystem services, savings derived from having those ecological services in place, and what it would cost society if services were destroyed. He estimated the average value of the world’s natural capital at $33 trillion per year – compared to global gross domestic product (GDP) at the time of just $18 trillion per year.

“It’s a redefinition of what the economy is and what it is for, a transdisciplinary effort to bridge the gap between human society and the environment,” said Costanza. “If you want to do a real study of the economy, you need to measure things that are outside the market.”

The EPA pilot project hopes to do just that for Tampa Bay. By estimating the value of Tampa Bay’s ecological services, the project’s leaders hope to provide tools and information to managers and policymakers who make informed decisions on economic development and land-use changes. By evaluating ecological services, the project will be able to forecast what the future holds for Tampa Bay.

The study comes at a critical turning point as planners determine how to accommodate growth in a region where the population will nearly double by the year 2050. Without a change in growth patterns, EPA models indicate that many of the distinctive wetlands and mangroves of Tampa Bay will be a thing of the past by the year 2060, replaced by seawalls as waterfront development continues and sea levels rise. With seawalls as the only line of protection, significant impacts to water quality and ecosystem health are likely to be caused by increased urban runoff.

Working in partnership with local organizations including the Tampa Bay Estuary Program, Agency on Bay Management, US Geological Survey, University of South Florida and local governments, the EPA project will delineate and quantify services provided by the Tampa Bay ecosystem.

The four place-based studies will result in a modular watershed approach which can be remixed in ways that define ecological services in other locales, notes Marc Russell, research ecologist. “Nobody has really looked at those numbers, how the ecosystems function together, and the services they provide.”

The Costanza numbers, for instance, assign monetary value to wetlands based on the total value of neighboring developed uplands. “A closer look at the connectivity between wetlands and upland areas and the capacity of different wetland types to mitigate storm events may lead to a modification of those values,” Russell said.

The dichotomy of Tampa Bay’s watershed, where highly developed urban areas ring its western and northern boundaries but publicly owned preserves dominate the southeastern border, also makes it a “natural experiment” for researchers, he adds. “We’ll be able to document the inevitable impacts of development on seagrasses and water quality.”

Mangroves Set Stage for Valuation

While mangroves are only part of Tampa Bay’s complex ecosystem, their importance as habitat is clear. Bordering the natural fringes of Tampa Bay, a tangled web of wood and vegetation occupies the shoreline. At the edge, where water meets land, mullet jump sporadically in the shallow water and stingrays burrow beneath the sand. White ibises and roseate spoonbills gradually maneuver their way across the shallow flats, through the tangled branches, feeding on small fish that shelter among the mangrove roots.

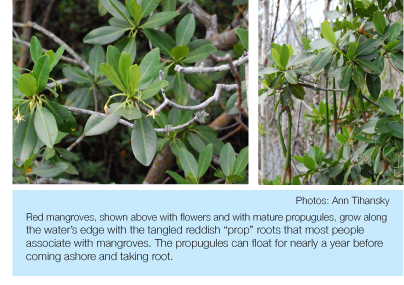

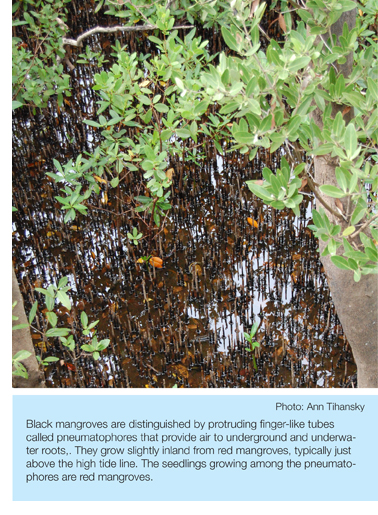

Mangrove forests are composed of several tropical and subtropical species that inhabit the coastal edge of the intertidal zones around the world where low-energy wave action allows them to cling to land. Mangroves are adapted to live on land while their roots are submerged occasionally in salty water. The intricate tangle formed when the branches and roots intertwine and overlap create a nearly impenetrable fortress that is home to numerous creatures and is one of the most productive ecosystems in the world.

“Mangroves stabilize a shoreline, catch and bind sediment, filter water, take up nutrients and provide protection for nearshore habitat,” said Tom Smith, an ecologist with the U.S. Geological Survey in St. Petersburg. “But probably the most important thing they do is support fisheries.”

The intricate root systems of mangroves and the bay’s extensive shallow coasts provide an ideal nursery for fish, shellfish and crustaceans. Protected from larger predators, a variety of marine life uses the bay shoreline to feed and grow.

“As leaves fall off these trees, they provide the basis of energy for the food chain and are a major producer in this ecosystem,” explained Brandt Henningsen, the chief environmental scientist of the Surface Water Improvement and Management (SWIM) program at the Southwest Florida Water Management District. The tangled mangrove roots also harbor important algae and phytoplankton that contribute basic fuel for the productive food webs of coastal waters.

The marine life that depends upon mangrove forests is vital to Florida’s commercial and recreational fishing industries, making mangroves a cash crop even though they weren’t planted as food. Billions of dollars are generated each year as recreational fishermen pursue snook, mullet, tarpon and snapper, or by commercial fisheries of snapper, grouper, shrimp and lobster. All rely, at some point in their lives, on mangrove habitat.

And unlike other crops, where substitutes can still generate income, removing a mangrove forest will cause a greater loss in overall services. For example, clearing a mangrove forest and replacing it with a seawall that costs thousands of dollars may provide short-term relief from storms. However, long-term benefits of habitat, water filtration, nutrient cycling, and other services will be lost.

A Misunderstood Resource

A Misunderstood Resource

Fifty years ago, as Florida’s population began to boom, the value of mangroves was not understood. They blocked scenic waterfront views and swarmed with constantly pesky and occasionally deadly malaria-carrying mosquitoes. In Tampa Bay, and across the country, mangrove forests were extensively ditched to connect isolated pockets of water bodies with the coast so that fish could access the wetlands and eat mosquito larvae.

“But in most of the places where mangroves were cleared, the clearing was followed by dredging and filling,” said Smith. “When they constructed the initial mosquito ditches, they piled up the spoil material on nearby wetlands, interfering with the natural tidal flows and creating a haven for invasive plants.”

As mosquito ditching methods were eventually abandoned, new threats to the region’s mangroves emerged. Populations soared, transforming the wet coastal environment into a hardened surface of concrete. Between 1960 and 1970, Florida’s population increased by 35% while wetlands were destroyed at an average rate of 72,000 acres per year. Dredging, draining and filling practices allowed for roads and subdivisions to replace inland wetlands. The altered natural drainage patterns and increased runoff into the bay resulted in deteriorating water quality.

“In heavily urbanized areas, water runs right off paved surfaces and brings with it heavy metals, pesticides and nutrients that will flush into streams and produce algae blooms that take up oxygen,” said Carole McIvor, USGS fishery biologist.

The loss of coastal wetlands and resulting poor water quality are correlated directly with observed declines in fish populations, said Robin Lewis, a longtime bay advocate and president of Lewis Environmental Services. “Records show quantities of fish caught and money derived from catches of mangrove dependent species like shrimp, red drum and mullet significantly dropped.”

The decreases in fish populations negatively impacted commercial and recreational fishing affecting Tampa Bay’s economy and altering biological relationships in coastal ecosystems.

“Fish are important not just because you catch and eat them or they are a source of commercial fishery, but because they link things,” Lewis continues. “Little fish eat something in the mangroves and then are eaten by big fish. Not all those big fish are caught and so they are eaten by even larger fish or birds. So there is just this tremendous interconnection going on.”

A Community’s Effort to Right the Wrongs

A Community’s Effort to Right the Wrongs

By the 1970s, coastal ecosystems in Tampa Bay were unraveling and large areas of the distinctive mangroves and wetlands had vanished. “When I started working on mangroves in the mid-70s, I began to go through the maps in conjunction with Carl Goodwin at the USGS and after we mapped and digitized the shoreline habitat from 1876 to the present, we came up with numbers indicating we had lost almost half of the mangroves and marshes on Tampa Bay,” said Lewis. “It was a pretty stark realization that led to the next question: ‘Can we get them back?’”

The link between removal of coastal wetlands and the decline in environmental quality and fish harvest sparked the recognition of the value of these habitats which, in turn, led to three decades of work by the scientific and environmental community to improve and protect the bay.

Over those years, mangroves have been a key component of restoration efforts, but mangrove restoration is not as straightforward as it may appear at first glance. It’s an expensive endeavor and simply planting mangroves, even in areas where they once occurred naturally, is not always successful.

“We typically do not plant mangroves,” said Henningsen, who is working on over 70 mangrove restoration projects. “Typically we plant marsh grasses, a very inexpensive, very forgiving plant, in areas where we know that mangroves will thrive. Once these grasses are established, mangrove seeds come in with the tide and lead to a natural succession.”

The process requires functional interaction between various components within the coastal ecosystem. “Before you restore, you need to understand the past distribution and ecology of mangroves to reestablish a hydrological regime that is functional,” said Lewis.

Restoring the Balance

Restoring the Balance

The importance of connections in the bay to the whole estuary system led to the development of a comprehensive estuary recovery plan by Tampa Bay Estuary Progam in 1996. “Restoring the Balance” focuses on restoring coastal ecosystems — including marshes, sea grasses and mangroves — to the same relative proportions that existed in 1950.

“The idea behind this comprehensive estuary recovery plan was that you need to understand what you had in order to understand what you want to get back to,” said Suzanne Cooper, principal planner of the Agency on Bay Management for the Tampa Bay Regional Planning Council.

Updated in 2008, the comprehensive conservation and management plan shows that mangrove forests have increased by 1000 acres since 1990. “Mangroves are growing in places where they may not have been 50 years ago,” Cooper said. That’s likely caused by high levels of nutrients from agricultural and urban development that encouraged mangrove growth in areas that had once been sandy beaches.

Projects like the estuary program’s “Restoring the Balance,” the USGS “Tampa Bay Integrated Science Study” and EPA’s “Ecological Research Program” are continuing to look at the estuarine system as a whole. Efforts are bringing together scientists, resource managers and the public to find economically sensible solutions to critical issues and to plan for the future. The integration of the scientific and environmental communities and knowledge of proper restoration techniques has made Tampa Bay an international center for success in mangrove restoration, said Lewis.

Balancing on the Edge

Despite gains, threats still loom for Tampa Bay. Though restoration and management plans have been successful in restoring mangrove forests, other habitats that link mangroves to coastal areas like salt marshes and salt barrens continue to decline. Continued losses to these natural systems caused by development could push back advances.

Of equal or greater concern is sea-level rise. The U.N. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change estimates sea level may rise anywhere from one to three feet over the coming century. In a flat, low-lying state like Florida, projected sea-level rise can affect even properties that seem far inland.

“From 1913 to 2007, sea level in Florida has come up eight inches,” says Smith. That may not sound like much until you consider that an eight-inch rise on a 1-to-100 slope is 800 inches -- or 66 feet inland.

While saltwater is moving inland, development continues along the coast. Stuck between man-made structures and a rising sea, mangroves could be squeezed out of Tampa Bay. “Some mangroves spend 30% of the time under water and 70% of the time dry,” said Lewis. “What that tells us about mangroves is that they are not nearly as loving of the water as people think. As sea level rises, too much water will stress mangroves and cause death.”

If shoreline development and sea-level rise continue at the same rate, Tampa Bay will probably lose all its mangroves in 100 to 150 years, said Lewis.

Anticipating responses to future growth and sea-level rise is of immediate concern. But many conservation and restoration efforts have not yet factored the prospect of sea-level rise in their planning scenarios. Ideas that may have seemed unconventional in the past -- such as using dredge materials to create islands where mangroves could naturally colonize -- may be necessary to provide habitat for marine life and other essential services these ecosystems supply.

One solution is to acquire more land near the coast. “Land-acquisition programs are critically important to the long-term success and productivity of Tampa Bay,” said Henningsen.

In 1990, voters of Hillsborough County authorized officials to expend up to $100 million to preserve environmentally sensitive land. Passage of the Environmental Lands Acquisition and Protection program (ELAPP) gave Hillsborough County officials the ability to protect thousands of acres of coastal habitat. In November of this year, voters will have the chance to continue the program and authorize officials to spend up to $200 million to acquire additional lands.

“At a time when there is a shortage of funding at all levels of the government, it is imperative that we have the ability to make future acquisitions of environmentally sensitive land,” said Dick Eckenrod, former director of the TBEP.

While purchasing all the environmentally sensitive land in the region isn’t an option, placing a monetary value on ecological services and natural capital can be a powerful tool for scientists, conservationists, planners and the public to protect the natural resources that remain. And in a world where we are trying to find a balance between human society and nature, placing a dollar sign on natural resources may be just the price to restore what we have lost and to protect what we have left.

Matthew Cimitile holds a bachelor’s degree in history from the University of Tampa and is working toward a master’s degree in environmental journalism from Michigan State University. He spent the summer of 2008 working with Ann Tihansky in science communications with the USGS in St. Petersburg, Florida.