Honoring a Conservation Legacy:

Passage Key National Wildlife Refuge

|

|

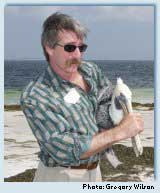

Marking a conservation milestone: Mark Ames, 55, greatgrandson of Teddy Roosevelt, releases a brown pelican as part of the celebration marking a century since Roosevelt established Passage Key as one of the nation’s first bird refuges.

|

By Mary Kelley Hoppe

We are huddled along the rails of a cabin cruiser circling a tiny island near the mouth of Tampa Bay, a small delegation assembled to mark an historic occasion – the 100th anniversary of Passage Key National Wildlife Refuge. All eyes are trained on the tiny spit of land, barely visible on the water horizon but bursting with wildlife, dozens of terns, a peregrine falcon and rare oystercatcher hunkered down against the breeze.

A century ago, on October 10, 1905, President Theodore Roosevelt signed an Executive Order establishing Passage Key as a federal bird reservation. Roosevelt would go on to create a total of 51 bird reservations and four national game preserves. These 55 “Roosevelt Refuges” were the start of what is known today as the National Wildlife Refuge System, encompassing more than 540 refuges and 100 million acres of America’s wild heritage.

Among the revelers are Roosevelt’s great-grandson, Mark Ames, former Congressman Sam Gibbons, and representatives of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the agency that oversees Passage Key and Tampa Bay’s two other national wildlife refuges: Pinellas National Wildlife Refuge (established in 1951) and Egmont Key National Wildlife Refuge (established in 1974 with Gibbon’s help).

“T.R. was a dedicated naturalist who realized how important this island was for birds and took advantage of his presidential powers to protect the birds and threatened wildlife habitat,” said Ames, on his first visit to Tampa Bay.

Nudged on by Audubon leaders fearing a lively plume trade would decimate the island’s avian settlers, Roosevelt asked the seminal question: “Is there any law that says I can’t do this?”

A century ago, Passage Key was a lush 60-acre barrier island with a freshwater lake harboring more than 102 species of birds. Today, the national wildlife refuge is a meandering island of less than five acres, but its stamp on the conservation landscape remains significant. The largest populations of royal and sandwich terns in all of Florida can be found at Passage Key and Egmont Key.

At a ceremony on Egmont Key marking the centennial, refuge managers received a $199,000 check to fund a new conservation partnership from Shell Oil Company (through the Shell Marine Habitat Program), the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Pinellas County Environmental Fund and the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation. A portion of those funds will help complete renovation of an historic guard house that once held prisoners of the third Seminole War. It will reopen next year as an environmental education center.

Passage Key is closed to the public because of its size and significance to shore-nesting birds, but visitors can learn about the refuge at its sister refuge.

While lauding the victories of America’s conservation movement, Gibbons, whose boyhood home on the Gulf shores overlooked a string of natural gems including Honeymoon Island, called on those present to carry on the work. “It won’t be done out of the glory of someone’s heart,” said Gibbons. “But you can inspire people to preserve these places as national wildlife refuges.

“So you all get busy – get it done.”

In honor of Passage Key’s 100th anniversary, the Friends of Tampa Bay Refuges are launching a campaign to recruit more members. To learn more, visit www.fcnwr.org.

|