|

||||||||

Tampa Bay Estuary Program celebrates its 20th anniversary this year with a series of events, including a travelling display of photos from the "Tampa Bay: 20/20" photo contest. St. Petersburg resident Peter Lousberg took top honors with this stunning image of an egret returning to its evening roost at Fort DeSoto Park. The photo is featured on TBEP’s commemorative poster which will be given to people participating in the 20th anniversary events. (See the Calendar of Events for details.)

By Victoria Parsons

Every family has one – the “problem child” who seems to stay in trouble even when everything else is going well.

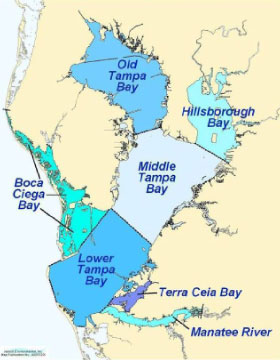

In Tampa Bay, the delinquent is Old Tampa Bay, the bay segment surrounded primarily by suburban neighborhoods in northwestern Hillsborough and central Pinellas counties. It not only receives stormwater runoff from a 160,000-acre watershed, but the problem is compounded by bridges and causeways that limit circulation in the segment.

Recognizing these unique challenges, the Tampa Bay Estuary Program teamed up with the Southwest Florida Water Management District’s (SWFWMD) Pinellas-Anclote River and Hillsborough River basin boards to develop a series of leading-edge solutions that will improve water quality and help restore natural resources, including seagrasses. Together, the water management district, TBEP and other partners have budgeted more than $10 million to restore Old Tampa Bay.

“Old Tampa Bay hasn’t responded to water quality improvement projects as well as the other segments, so it needed to become a priority,” said Jennette Seachrist, manager for SWFWMD’s Surface Water Improvement and Management (SWIM) program. “The additional funds from the basin boards will allow us to take a more in-depth look at what is causing the slower response and begin implementing a restoration strategy.”

Few people realize that Old Tampa Bay is lagging behind the rest of the estuary, adds Hugh Gramling, vice chairman of the district’s governing board and co-chair of its Hillsborough River Basin Board. “We need to understand what’s going on so we can go in and correct it.”

The first step is an integrated model that looks at the multiple issues impacting Old Tampa Bay to:

- Determine the effect of causeways and bridges on circulation and develop recommendations for modifications that would enhance circulation. Computer models will look at the potential impact of culverts that could allow water to flow underneath the Howard Frankland and Courtney Campbell causeways.

- Explore the potential of re-directing flow from Lake Tarpon to the Anclote River. Historically, much of the Lake Tarpon watershed drained into the Gulf of Mexico through the Anclote River. The Lake Tarpon Outfall Canal, built in the 1960s for flood control, redirected that flow to Old Tampa Bay. Results of the Safety Harbor Sediment Study indicate that nutrients, primarily from residential fertilizer used in the Lake Tarpon/Brooker Creek watershed and other watersheds around Old Tampa Bay, are a likely cause of increased sediment accumulation in Old Tampa Bay. Reconnecting the historic route could remove some of the nutrients from the bay segment.

- Identify and develop habitat restoration opportunities along the Lake Tarpon Outfall Canal. Public lands along the canal could be restored as functional wetlands where flows from the lake would be diverted to allow biological removal of nutrients before entering Old Tampa Bay.

- Explore appropriate uses for reclaimed water from the Clearwater East wastewater treatment plant.

- Develop projects to minimize urban runoff. Bay managers are hopeful that the new ban on rainy season fertilizer application and sales in Pinellas County will result in a significant decrease in the level of nutrients in stormwater. Hillsborough County also has enacted a fertilizer rule that relies heavily on education to reduce fertilizer runoff from lawns.

- Analyze and develop management actions to minimize the causes and extent of algal blooms in Old Tampa Bay. The Tampa Bay Estuary Program budgeted $200,000 in February 2010 for in-depth research on the issues facing Old Tampa Bay including a better understanding of the nutrient forms, delivery, timing and impact duration.

“We expected to see greater improvements in water quality and seagrasses with the management actions that have already been taken,” Seachrist added. “We’ve picked the low-hanging fruit, so now we need to dig a little deeper to see what actions will make a difference in this bay segment.”

Restoration Already Underway

While a large portion of the funds budgeted to improve water quality in Old Tampa Bay focus on the comprehensive modeling initiative, on-the-ground efforts also are underway, including an innovative public-private initiative with Feather Sound Golf Course.

The golf course, which uses reclaimed water from the city of Largo, had already begun looking at removing up to 30 acres of turf to save time and money on maintenance. TBEP has developed additional plans to enhance the pond areas with native plantings and develop new streams to connect ponds and keep stormwater onsite for longer periods of time.

Additionally, plans are being finalized to restore about five acres of mangroves ringing the bay and monitor changes in water quality as well as fish utilization and impacts on nearby seagrasses. A primary focus will be filling and regrading mosquito ditches so stormwater can move slowly through the natural systems, allowing mangroves and marsh grasses to remove more of the nutrients in the water.

The new SWFWMD funding will allow TBEP to expand the restoration efforts to encompass more of the approximately 640 acres of public lands along Old Tampa Bay.

Tidal Tributaries Targeted

Another effort the SWFWMD funding will jumpstart in Old Tampa Bay is the restoration of tidal tributaries. Many of those tributaries are at least partially blocked by weirs, culverts, roads or by obsolete structures designed to contain fresh water in ponds for irrigation of farmland that has since been developed.

The tidal tributaries provide critical low-salinity habitat and blocking those systems may cause dramatic “pulses” of stormwater rather than natural moderated flows. They also are the clearly preferred habitat for several species of fish and a recent TBEP ecological assessment found up to 36 times more snook in streams than in adjacent bay waters.

TBEP, with funding from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, has been assessing tidal tributaries that flow into Old Tampa Bay to catalog salinity barriers and then to prioritize specific tributaries for restoration. New SWFWMD funding will allow TBEP to perform a pilot study on one or more salinity barriers as well as developing site plans and securing permits for up to three other tributaries in the Old Tampa Bay watershed.

TBEP is also expanding the assessment of tidal tributaries across the entire bay to look for opportunities in other watersheds. “We will have the opportunity to prioritize the tributaries where restoration can make the biggest difference,” said Ed Sherwood, TBEP program scientist. “One option we’ll consider is creating low-salinity habitat with reclaimed wastewater – it’s been very successful in other estuaries in the Gulf of Mexico.”

Seagrasses Stage Baywide Gain

Seagrasses across Tampa Bay – including Old Tampa Bay – are growing in areas where they haven’t been seen in 60 years, according to a new report released in late January. The bay gained 3,250 acres of seagrass between 2008 and 2010 – an 11% increase that is the largest two-year expansion of seagrasses since scientists began regular surveys of this critical underwater habitat.

Seagrasses across Tampa Bay – including Old Tampa Bay – are growing in areas where they haven’t been seen in 60 years, according to a new report released in late January. The bay gained 3,250 acres of seagrass between 2008 and 2010 – an 11% increase that is the largest two-year expansion of seagrasses since scientists began regular surveys of this critical underwater habitat.

Old Tampa Bay gained 858 acres of seagrasses, among the largest increases seen baywide. Much of that gain, however, was in areas that have not been adversely impacted by poor circulation or stormwater inputs. Losses were documented in areas to the north and west of the Courtney Campbell Causeway and offshore near the St. Petersburg Clearwater Airport.

“This report underscores how important it is that we understand what’s happening in Old Tampa Bay so we can decide how to best manage it,” said Lindsay Cross, TBEP scientist.