|

||||||

|

||||||

From Tampa Bay with Love

Florida Aquarium, UF’s Tropical Aquaculture Lab

Growing Coral to Restore Reefs in Florida Keys

Coral might be the slowest-growing crop ever farmed, but researchers say damaged reefs could be repaired faster if they perfect methods to cultivate the marine organisms. The Florida Aquarium, working with researchers from the University of Florida’s Tropical Aquaculture Laboratory in Ruskin and Mote Marine Laboratory’s Summerland Key station, is helping to make that happen.

“With the loss of naturally growing coral, it is imperative we determine the causes of its destruction and then methods to supplement the loss with new growth, like seeding native waters with healthy coral fragments,” said Ilze Berzins, vice president of biological operations for the Florida Aquarium. “It is too important a natural resource to be overlooked simply because its devastation isn’t apparent due to its location.”

|

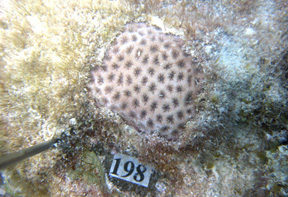

| Photos courtesy The Florida Aquarium Placing transplanted coral sections back in living reefs is a time-consuming process, with four divers each spending 70 minutes under water to attach 88 coral fragments. Each is numbered and will be monitored for growth. |

Seven coral species were harvested from an underwater sea wall at the U.S. naval base in Key West Harbor. Planned offshore sea wall construction threatened to encase or destroy existing corals, so the state and the sanctuary granted a collecting permit. Last year, almost 160 cookie-sized coral fragments were placed at a reef near Key West where a freighter ran aground in 1993. The reef is within the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary, a protected area that comprises most of the Florida Keys.

“If you grow coral in a greenhouse in a land-based system and put it in the wild, will it survive?” asks Craig Watson, director of the Tropical Aquaculture Laboratory. “There are those who say no, because it will be acclimated to those conditions where it grew and it can’t survive elsewhere. We don’t believe that, and we are setting out to prove that wrong.”

Testing the Waters

Fragments placed at the Key West site had been managed in one of three ways, Watson said. One set was raised in a Ruskin greenhouse, held in tanks of artificial seawater. Another was cultured at the Mote Marine Laboratory facility at Summerland Key, using an outdoor system with seawater pumped from offshore. A third was placed on the damaged reef almost immediately after harvest. Each fragment is numbered so it can be tracked.

Colonies of larger fragments are being held in a rooftop greenhouse at The Florida Aquarium in Tampa, said Ryan Czaja, a supervisor who handles day-to-day care of the colony. Czaja also was part of a team that collected the coral. “It was tough diving,” Czaja said. “We were out in the channel and there was a lot of water flow, visibility was about four feet…But nothing dangerous or we wouldn’t have been down there.”

Berzins, working with Roy Yanong at the Tropical Aquaculture Laboratory, developed a standard to properly quarantine corals in culture and ensure corals intended for reintroduction are healthy prior to restoration. This includes an actual health certificate, signed by a veterinarian, to confirm that the corals are ready for seeding. This is the first time the health of the coral fragments has been addressed prior to their return to open water.

|

“As the study advanced, many additional questions have arisen that could impact the successful use of aquacultured corals to rehabilitate reefs,” said Berzins. “We have expanded our partnership to include marine microbial biologists from the University of South Florida and geneticists from Florida Atlantic University.”

Planting the Seeds

The process for seeding coral begins with a small fragment extracted from an already living coral. The fragment is attached to a small cement disk and allowed to culture for about six months. The time allowed for culturing the fragment accomplishes several things.

“First, the fragment grows over where it was cut, and that increases its chance of survival,” said Watson. “Secondly, we can accurately determine their general health – if they are doing well after six months they should be healthy enough to plant in the open water. And finally, the time in culture serves as a quarantine period so that any potentially disruptive illnesses can be addressed before placing the fragments among other living coral.”

The fragments need to be attached to areas that will provide a nurturing place for them to grow. It sounds a great deal like planting seeds for cultivating crops. “If you attach a fragment to an area that doesn’t get direct sunlight or is going to be ravaged by strong surges you decrease the likelihood the fragment will successfully grow,” said Watson.

Once a location for a fragment has been determined, it is a time-consuming process to attach each fragment to the new site. “We had six divers do four 70-minute dives each to plant 88 fragments,” said Berzins. “That is 24 dives of more than an hour each. Yes, it’s quite time consuming.”

The fragments, attached to the reef with epoxy, are scattered over two areas, each measuring several hundred square meters and will be monitored at three- and six-month intervals,” said Berzins, who hopes to receive additional funding to continue the research. “Our goal is to develop a proven, successful method for healthy reef restoration – and our marine life depends on it.”

Fun Facts About Coral

Compiled from reports from The Florida Aquarium and the University of Florida.

Future of Florida Farming May Be Rising in Dover

Don Whyte: Greening the Vision of Development

Estuary Program Awards $160,000 in Community Grants

Mote's Founding Director Celebrates her 85th Birthday

The Pier Aquarium Prepares For its Grand, Grand, Grand Reopening