The Playbook is already starting to pay back in Sarasota County.

The Community Playbook for Healthy Waters, published by the Gulf Coast Community Foundation in November 2021, has already exceeded its authors’ expectations both locally and nationally, helping communities address water quality issues on multiple levels.

The most significant impact is Sarasota County’s commitment to upgrading its wastewater treatment facilities to advanced wastewater treatment (AWT), which was shown to provide the best return on investment for removing nutrients from Sarasota Bay.

“We could demonstrate, using county data, that converting to AWT would remove the greatest amount of nutrients for the least amount of dollars,” said Jon Thaxton, senior vice president of the foundation, a longtime environmental advocate and a former county commissioner. “It will cost millions to upgrade the plants, but it is still the lowest price per pound to remove the nutrients.”

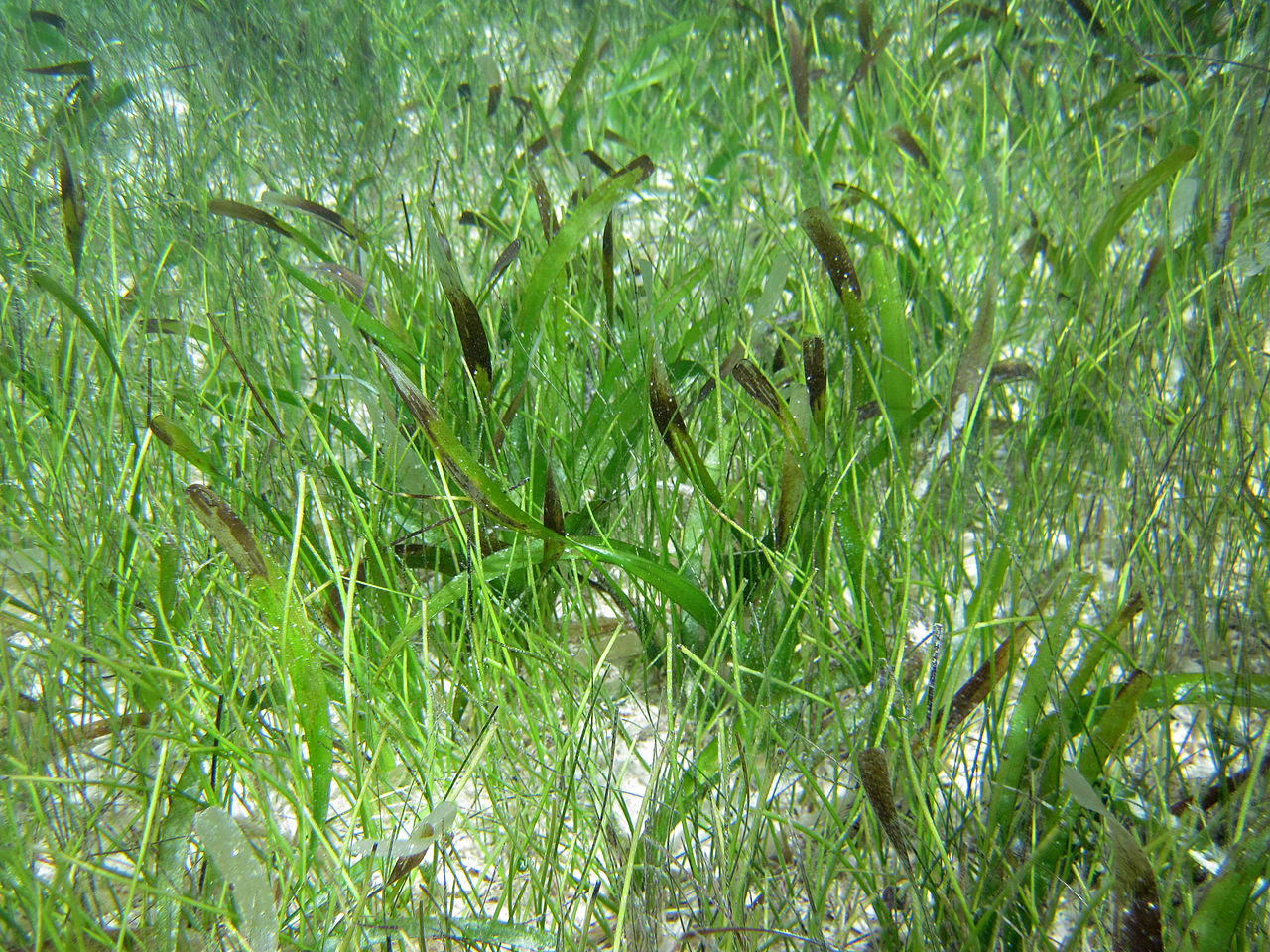

Nutrients, from wastewater, stormwater and atmospheric deposition, are the leading cause of pollution in most urban estuaries. An overabundance of nitrogen and phosphorus fuels the growth of algae, which blocks sunlight from reaching seagrass beds and consumes oxygen as it decays. Seagrass acreage in both Sarasota and Tampa bays has declined recently as nutrient loadings have increased.

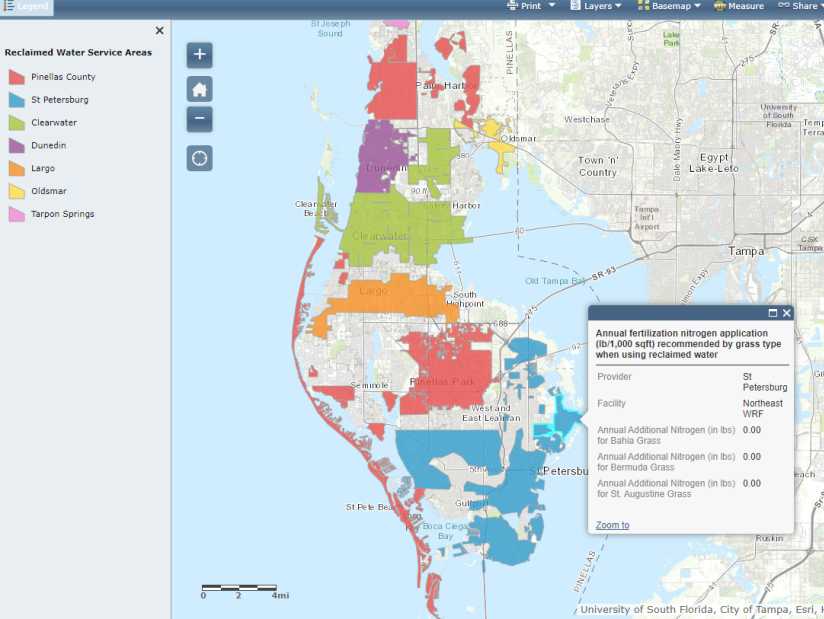

As the county invests in upgrading its treatment facilities, the Playbook calls for working with golf course managers and homeowners associations to limit the use of fertilizer when using reclaimed water. In some cases, that water contains so many nutrients that just watering a lawn exceeds state recommendations for fertilizer, Thaxton said. A recent evaluation of fertilization needs compared to the nutrients in reclaimed water at one local golf course shows the course needed 15,385 pounds of nitrogen but got 16,529 just in their reclaimed water.

Focusing on the financial impact of fertilizer will encourage large users to cut back and save money, even beyond the benefits to water quality and wildlife. “We can talk to golf course managers and tell them to forget about birds and wildlife – we can save you lots of money on fertilizer,” Thaxton said. “When we talk to homeowners associations about water quality and habitats, then we can tell them how much money they can save on maintaining their stormwater ponds if they cut back on landscape fertilizer.”

Best-Available Science Translates to Actionable Activities

The Playbook – which is designed as a living document created to provide decision-makers with the information they need – takes the best available science and organizes it into 43 actionable activities that range from the millions of dollars that need to be invested in AWT to campaigns educating residents about the link between emissions from gasoline engines and water quality.

While the data comes from Sarasota County, the playbook works well in any coastal community in Florida because the issues are so similar. Pinellas County, for instance, already measures nutrients in reclaimed water so residents know how to fertilize appropriately. Several of the action items, such as improving the Florida Department of Environmental Protection’s reporting on wastewater discharges, would automatically impact Tampa Bay. Other research, like quantifying the cost and effectiveness of nutrient reduction options for septic tanks, could easily be translated in Tampa Bay.

More research into best management practices (BMPs) for stormwater is another action item that could impact the entire state. Most local governments approve new construction based on data available from conventional BMPs, like building retention ponds and creating wetlands, which are widely accepted but more difficult to implement in urban settings.

On the other hand, low-impact development or “green” infrastructure, like permeable pavement, bioswales and green roof systems, are still considered to be provisional and accepted by regulatory agencies on a case-by-case basis. New research supports their efficacy but creating a statewise database that identifies their return on investment would make them easier to implement both for regulators and developers.

Closer to home but with statewide implications is a call to update local ordinances with BMPs for stormwater pond maintenance. Although the ponds are typically built to clear specifications, standards for long-term maintenance are lacking. The Playbook calls for local ordinances that would ensure that stormwater ponds maintain their ability to efficiently remove nitrogen as well as protect nearby residences against flooding.

Foundation Has Sense of Urgency

It all began with an informal meeting bringing more than a dozen diverse stakeholders to the table, from engineers and scientists to stormwater, wastewater and utility professionals as well as business and agricultural interests. “We talked about what we wanted to do and gave everyone the opportunity to leave – no one did,” Thaxton said.

Then when the final draft was complete, they took it back to the professionals and asked them to critique the data and point out errors or deficiencies. “We made some changes, but we wanted to know everyone was onboard with it.”

Like Tampa Bay, water quality in Sarasota Bay dramatically improved in the early 1990s, spurring huge increases in seagrass beds that were directly attributable to limited nitrogen inputs. After severe losses in 2014 to 2018, seagrasses are rebounding again but Thaxton says it’s critical to hold the line on nitrogen inputs. “There’s a sense of urgency, that we could lose everything we’ve gained if we don’t continue to limit nitrogen inputs.”

And while the Gulf Coast Community Foundation continues to focus on traditional areas like homelessness, the arts, and education, expanding its efforts to include water quality was a logical step, Thaxton said. “Beaches and the environment are the economic drivers of the entire region, but they could be our nemesis. We need to make sure that that goose continues to lay golden eggs.”