Although giant snakes and poisonous frogs may terrify the average homeowner, the species that cause the worst nightmares for land managers can be found in backyards across the region.

- That bush that sports thousands of bright red berries right around Christmas? It’s probably Brazilian pepper, one of the most aggressive pests in Florida. It now covers more than 700,000 acres across the state in a dense canopy that chokes out other species. Birds, however, love those little red berries and are a primary reason it has spread so widely.

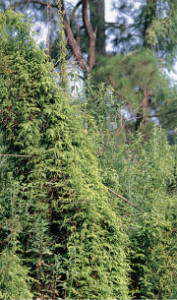

- That charming little fern that just appeared in an empty pot and is clambering up an oak tree? That might be lygodium, a climbing fern that is shading out native vegetation on hundreds of acres across Florida and the southeast. It spreads quickly by throwing thousands of wind-born spores and is changing the fire ecology in some nature preserves.

- Or the sneaky vine with opposite leaves and little white flowers that crawls along the ground putting down new roots at every growing node until it leaps up to take over a fence and spread seeds everywhere? Skunkvine, imported from Asia in the late 1800s as a source of fiber, has become a significant threat to habitat in the 17 Florida counties where it is found, including Pasco and Hillsborough.

It’s hard to put a number on the dollars spent every year battling exotic plants and animals because it includes initiatives at the federal, state and local levels from dozens of agencies ranging from parks and recreation to environmental protection agencies and water management districts. One report, compiled for the state’s Invasive Species Working Group, estimated costs of more than $100 million in 2004, although that included the war on citrus canker funded through state and federal agricultural departments.

Most Wanted

BRAZILIAN PEPPER

Almost every newcomer to Florida comments on the beauty of a Brazilian pepper “tree” covered in bright red berries in mid- to late December. Beyond that beautiful facade, however, lies one of the most important threats to Florida’s natural areas.

Almost every newcomer to Florida comments on the beauty of a Brazilian pepper “tree” covered in bright red berries in mid- to late December. Beyond that beautiful facade, however, lies one of the most important threats to Florida’s natural areas.

“If you rank the top five invasives in the Tampa Bay watershed, Brazilian pepper is number one, two, three and four,” says Nanette O’Hara, outreach coordinator for the Tampa Bay Estuary Program. “They’re everywhere and they’re extremely difficult to kill, particularly when local governments are suffering budget cuts.”

Usually a thick, gangly shrub, the Brazilian pepper covers more than 700,000 acres in Florida – an area almost as large as Hillsborough County’s total land mass. It aggressively invades shorelines, choking out mangroves in marine habitats and native species lining lakes, rivers and streams. It also thrives in uplands, where it quickly becomes a monoculture, producing a dense canopy where nothing else can live. A close relative of poison ivy, it can cause skin irritation and its pollen can cause respiratory irritation. Birds eat the berries and spread its seeds, but otherwise it has no value as habitat. It’s now illegal to sell or plant Brazilian pepper and they should be destroyed whenever possible. If simply cut down, they’ll resprout from the trunk and roots. Smaller plants should be dug up, larger plants should be cut back to the ground and stumps treated immediately with triclopyr ester (Garlon 4, Pathfinder or Vine-X). Be sure to dispose of branches with berries in plastic trash bags – even berries that aren’t ripe when you cut them can sprout if they are left outside. Biocontrols, like the tiny weevil that is taking out melaleuca, are problematic for Brazilian pepper because it is closely related to several native Florida plants. The more closely related plants are, the more likely that the biocontrols will damage other plants, which automatically disqualifies them for release.

LYGODIUM OR CLIMBING FERN

Like many invasive species, climbing fern is an attractive, easy-to-grow plant that was originally imported as a landscape specimen. It’s becoming a significant threat to Florida habitats. In Tampa Bay, the species most likely to be seen is Lygodium japonicum, or Japanese climbing fern. Further south, Lygodium microphyllum, or old-world climbing fern, now covers hundreds of thousands of acres, completely engulfing some Everglades tree islands. “It’s been sneaking up on us over the last decade or so but it really expanded in the last couple of years,” notes Brian Nelson, aquatic plant manager at the Southwest Florida Water Management District. “The old world species seems to be more invasive – it grows faster and has a larger biomass.” Both species spread with tiny spores that can be wind-blown nearly anywhere. An individual plant may grow to 90 feet long, forming a dense “living wall” that chokes out even healthy tree canopies. It thrives in sun or in shade, in shallow water or in dry locations, and invades even undisturbed sites. In backyards and neighborhoods, it can be controlled by cutting it back to knee-height and then spraying herbicide. Remove as many fronds as possible to prevent the spread of spores and know that you’ll probably need to repeat the treatment. It’s harder to kill in natural areas where it may be growing in wetlands or seasonably wet areas that aren’t accessible by truck or even ATV. “You have to cut the vine at the base of the tree and spray it with an herbicide,” Nelson said. “That makes it a lot more difficult when it’s hard to get access to the plant.”

Like many invasive species, climbing fern is an attractive, easy-to-grow plant that was originally imported as a landscape specimen. It’s becoming a significant threat to Florida habitats. In Tampa Bay, the species most likely to be seen is Lygodium japonicum, or Japanese climbing fern. Further south, Lygodium microphyllum, or old-world climbing fern, now covers hundreds of thousands of acres, completely engulfing some Everglades tree islands. “It’s been sneaking up on us over the last decade or so but it really expanded in the last couple of years,” notes Brian Nelson, aquatic plant manager at the Southwest Florida Water Management District. “The old world species seems to be more invasive – it grows faster and has a larger biomass.” Both species spread with tiny spores that can be wind-blown nearly anywhere. An individual plant may grow to 90 feet long, forming a dense “living wall” that chokes out even healthy tree canopies. It thrives in sun or in shade, in shallow water or in dry locations, and invades even undisturbed sites. In backyards and neighborhoods, it can be controlled by cutting it back to knee-height and then spraying herbicide. Remove as many fronds as possible to prevent the spread of spores and know that you’ll probably need to repeat the treatment. It’s harder to kill in natural areas where it may be growing in wetlands or seasonably wet areas that aren’t accessible by truck or even ATV. “You have to cut the vine at the base of the tree and spray it with an herbicide,” Nelson said. “That makes it a lot more difficult when it’s hard to get access to the plant.”

CUBAN TREE FROGS

When a university professor whose email address begins with tadpole recommends the widespread trapping and euthanasia of frogs, it’s obviously a serious issue. But without intervention, Cuban tree frogs may relentlessly spread across the state, taking over habitat once used by native species, says Steve Johnson, an assistant professor of wildlife ecology at the University of Florida’s Gulf Coast Research and Education Center. Johnson began enrolling “citizen-scientists” last fall in a program that identifies, traps and then euthanizes Cuban tree frogs. “We don’t like killing frogs, but we need to protect our native species,” he said. Ongoing reports indicate that it’s very rare to find native tree frogs in areas where Cuban tree frogs live. “They eat the same food a native frog eats, plus they eat native frogs too,” Johnson said. They’re also larger than native tree frogs and breed more prolifically – one female can lay up to 15,000 eggs per year in places a native frog would not. “Almost anytime you see a large number of tadpoles in standing water, they’re Cuban tree frogs,” he said. Johnson is hopeful that eliminating Cuban tree frogs in some neighborhoods will allow native populations to rebound. “We’re hearing reports that people are seeing native tree frogs again after they started to capture and humanely euthanize the invaders.” For more information, including photos and details about telling Cuban tree frogs from native species, visit http://ufwildlife.ifas.ufl.edu/citizen_sci.shtml or e-mail Johnson at tadpole@ufl.edu.

When a university professor whose email address begins with tadpole recommends the widespread trapping and euthanasia of frogs, it’s obviously a serious issue. But without intervention, Cuban tree frogs may relentlessly spread across the state, taking over habitat once used by native species, says Steve Johnson, an assistant professor of wildlife ecology at the University of Florida’s Gulf Coast Research and Education Center. Johnson began enrolling “citizen-scientists” last fall in a program that identifies, traps and then euthanizes Cuban tree frogs. “We don’t like killing frogs, but we need to protect our native species,” he said. Ongoing reports indicate that it’s very rare to find native tree frogs in areas where Cuban tree frogs live. “They eat the same food a native frog eats, plus they eat native frogs too,” Johnson said. They’re also larger than native tree frogs and breed more prolifically – one female can lay up to 15,000 eggs per year in places a native frog would not. “Almost anytime you see a large number of tadpoles in standing water, they’re Cuban tree frogs,” he said. Johnson is hopeful that eliminating Cuban tree frogs in some neighborhoods will allow native populations to rebound. “We’re hearing reports that people are seeing native tree frogs again after they started to capture and humanely euthanize the invaders.” For more information, including photos and details about telling Cuban tree frogs from native species, visit http://ufwildlife.ifas.ufl.edu/citizen_sci.shtml or e-mail Johnson at tadpole@ufl.edu.

FERAL HOGS

Some invaders have been in Florida so long that many people don’t realize they’re not natives. When Hernando DeSoto arrived in Florida in 1539, he brought 200 pigs. Today, there are an estimated four million feral hogs – including descendants of DeSoto’s pigs – living in the southeastern US. They cause about $800 million in damage every year. Truly omnivorous, they’ll eat almost anything from grass, nuts and berries to insects and small animals. They cause the most damage, however, when they dig for roots and tubers, leaving land totally devoid of any plants and covered in ruts up to 15 inches deep. When the ruts occur near rivers or streams, they cause erosion and sedimentation to increase, negatively impacting water quality. Disturbing the land allows nuisance plants to invade. There isn’t an easy way to control – or even to count – feral hogs, notes Paul Elliott, senior land manager for the Southwest Florida Water Management District. “They’re very smart animals and they’re pretty elusive,” he said. “We estimate populations by the damage they’re causing.” The district opens lands to hog hunters for six days every year and available slots fill up in minutes. “That’s the best way we have to control them right now but we still need to balance recreational use with the night-time hunts,” Elliott said. Scientists also are looking at ways to sterilize the hogs to slow down their population growth. The challenge is finding a bait that is species-specific so no other animals eat it, or devising an enclosure where they can be trapped and vaccinated with a shot that would sterilize them for life.

Some invaders have been in Florida so long that many people don’t realize they’re not natives. When Hernando DeSoto arrived in Florida in 1539, he brought 200 pigs. Today, there are an estimated four million feral hogs – including descendants of DeSoto’s pigs – living in the southeastern US. They cause about $800 million in damage every year. Truly omnivorous, they’ll eat almost anything from grass, nuts and berries to insects and small animals. They cause the most damage, however, when they dig for roots and tubers, leaving land totally devoid of any plants and covered in ruts up to 15 inches deep. When the ruts occur near rivers or streams, they cause erosion and sedimentation to increase, negatively impacting water quality. Disturbing the land allows nuisance plants to invade. There isn’t an easy way to control – or even to count – feral hogs, notes Paul Elliott, senior land manager for the Southwest Florida Water Management District. “They’re very smart animals and they’re pretty elusive,” he said. “We estimate populations by the damage they’re causing.” The district opens lands to hog hunters for six days every year and available slots fill up in minutes. “That’s the best way we have to control them right now but we still need to balance recreational use with the night-time hunts,” Elliott said. Scientists also are looking at ways to sterilize the hogs to slow down their population growth. The challenge is finding a bait that is species-specific so no other animals eat it, or devising an enclosure where they can be trapped and vaccinated with a shot that would sterilize them for life.

What’s New?

LION FISH

Just looking at a lionfish with its floating striped head, it’s easy to see why they’ve become a popular choice for an aquarium. Looking at them consume native fish in a coral reef off the Florida Keys, it’s easy to see how they’ve become the poster child – as if Florida needed another one – for demonstrating the danger of exotic species. Apparently released into Biscayne Bay after Hurricane Andrew, the lionfish has spread north to the Carolinas and southwest to the marine sanctuary at Dry Tortugas. One found in the Gulf of Mexico is thought to have been recently released, but it’s likely to be only a matter of time before they become an issue here. Voracious predators, lionfish eat enormous numbers of smaller fish, taking away food sources that important species such as grouper and snapper depend upon. They also eat reef-cleaning species, such as the colorful parrot fish, which could stress fragile coral. In fact, a small study in the Bahamas indicates that lion fish reduced net recruitment of native fish by 79% on coral reefs there. And with poison spines that cause excruciating pain, they have no predators – except humans. Recognizing the potential for damage the National Oceanic Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), which oversees marine sanctuaries in the Florida Keys, is issuing permits to trained people to remove lionfish from no-take zones. The Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission has removed size limits on lionfish at the John Pennekamp State Park in Key Largo in hopes of controlling the invader there.

Just looking at a lionfish with its floating striped head, it’s easy to see why they’ve become a popular choice for an aquarium. Looking at them consume native fish in a coral reef off the Florida Keys, it’s easy to see how they’ve become the poster child – as if Florida needed another one – for demonstrating the danger of exotic species. Apparently released into Biscayne Bay after Hurricane Andrew, the lionfish has spread north to the Carolinas and southwest to the marine sanctuary at Dry Tortugas. One found in the Gulf of Mexico is thought to have been recently released, but it’s likely to be only a matter of time before they become an issue here. Voracious predators, lionfish eat enormous numbers of smaller fish, taking away food sources that important species such as grouper and snapper depend upon. They also eat reef-cleaning species, such as the colorful parrot fish, which could stress fragile coral. In fact, a small study in the Bahamas indicates that lion fish reduced net recruitment of native fish by 79% on coral reefs there. And with poison spines that cause excruciating pain, they have no predators – except humans. Recognizing the potential for damage the National Oceanic Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), which oversees marine sanctuaries in the Florida Keys, is issuing permits to trained people to remove lionfish from no-take zones. The Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission has removed size limits on lionfish at the John Pennekamp State Park in Key Largo in hopes of controlling the invader there.

GIANT SNAILS

Giant snails may not provoke the same response as poisonous fish but they likely pose a greater threat to natural areas in Tampa Bay. One species – the giant African snail – had been eradicated once with a $1 million 10-year effort only to return earlier this year. A number of the snails were found in a home near Miami earlier this year, apparently imported for a religious rite, and officials sounded the warning before they could spread across the state. Among the largest land snails in the world, Achatina fulica can grow up to eight inches long. Each snail contains both male and female reproductive organs and a single snail can lay up to 1,200 eggs a year. They eat more than 500 types of plants – as well as stucco and plaster – and could devastate both agricultural industries and natural areas. They also carry parasites and the meningitis bacteria so they pose an immediate issue for human health. A smaller non-native apple snail already is widespread in aquatic areas across the state as far north as Tallahassee. Although larger than the native apple snail, it’s much smaller than the African snail. Land managers are concerned that the imported snails may displace the native species, potentially disrupting other species including the endangered Everglades snail kite. The snail kite normally feeds on native apple snails the size of a golf ball with its distinctive hooked beak. The exotic snails grow to be larger than tennis balls and scientists are watching to see if the birds, particularly young birds, can handle the extra-large prey.

Giant snails may not provoke the same response as poisonous fish but they likely pose a greater threat to natural areas in Tampa Bay. One species – the giant African snail – had been eradicated once with a $1 million 10-year effort only to return earlier this year. A number of the snails were found in a home near Miami earlier this year, apparently imported for a religious rite, and officials sounded the warning before they could spread across the state. Among the largest land snails in the world, Achatina fulica can grow up to eight inches long. Each snail contains both male and female reproductive organs and a single snail can lay up to 1,200 eggs a year. They eat more than 500 types of plants – as well as stucco and plaster – and could devastate both agricultural industries and natural areas. They also carry parasites and the meningitis bacteria so they pose an immediate issue for human health. A smaller non-native apple snail already is widespread in aquatic areas across the state as far north as Tallahassee. Although larger than the native apple snail, it’s much smaller than the African snail. Land managers are concerned that the imported snails may displace the native species, potentially disrupting other species including the endangered Everglades snail kite. The snail kite normally feeds on native apple snails the size of a golf ball with its distinctive hooked beak. The exotic snails grow to be larger than tennis balls and scientists are watching to see if the birds, particularly young birds, can handle the extra-large prey.

AMBROSIA BEETLES

A newly introduced ambrosia beetle is threatening both native trees and Florida’s $30 million avocado industry. The tiny beetle carries a fungus that causes the tree to die within a few months of infection. At the site of the original fungus infection, 90% of redbay trees – an important food source for wildlife ranging from black bears to the Palamedes swallowtail butterfly – died in only 15 months. A native of India, the ambrosia beetle probably slipped into this country in wooden pallets. While scientists are working on control for the ambrosia beetle, they caution residents not to transport firewood and mulch made with redbay or related trees including sassafras, avocado, swampbay, camphor and the endangered pondberry.

A newly introduced ambrosia beetle is threatening both native trees and Florida’s $30 million avocado industry. The tiny beetle carries a fungus that causes the tree to die within a few months of infection. At the site of the original fungus infection, 90% of redbay trees – an important food source for wildlife ranging from black bears to the Palamedes swallowtail butterfly – died in only 15 months. A native of India, the ambrosia beetle probably slipped into this country in wooden pallets. While scientists are working on control for the ambrosia beetle, they caution residents not to transport firewood and mulch made with redbay or related trees including sassafras, avocado, swampbay, camphor and the endangered pondberry.

Whatever Happened To?

MELALEUCA

From the road, it’s not immediately apparent that melaleuca has lost its hold on the Everglades. Look more closely, though, and you’ll see that there are fewer small trees and they’re actually losing ground. “The big trees may still be there, but they’re not invasive anymore,” says Philip Tipping, an entomologist with the USDA’s Agricultural Research Service. “We’ve cut seed production by 99% so you no longer see the carpets of seedlings moving through the landscape the way you used to.” A series of insects – also known as biocontrols – were released beginning in 1997. To document their efficacy, Tipping and his team sprayed pesticides on a plot of melaleuca growing in a cypress-pine wetland every month for five years. Trees that were treated with pesticides to control the introduced insects were nearly 50% more dense after five years, compared to an increase of less than one percent on the unsprayed plots. Biocontrols have been used for years to control pests although some – like the cane toad imported to eat beetles in sugarcane fields – have actually become pests themselves. ARS scientists are now charged with ensuring that any biocontrols imported won’t eat other plants. “Most insects only feed on a very few plants, most often plants that are closely related to each other,” Tipping said. Other biocontrols are being released now for both lygodium and water hyacinths although it’s still too early to tell what kind of impact they might have. Some biocontrols, like a mite released to eat lygodium, don’t naturalize well for reasons scientists may never understand. Having melaleuca under control, however, means that land managers can focus on other species without having to be concerned that the melaleuca will come back. “Those big trees may live for a long time but realistically they’re no longer a threat so managers can cut them down when they get around to it.” Tipping said.

From the road, it’s not immediately apparent that melaleuca has lost its hold on the Everglades. Look more closely, though, and you’ll see that there are fewer small trees and they’re actually losing ground. “The big trees may still be there, but they’re not invasive anymore,” says Philip Tipping, an entomologist with the USDA’s Agricultural Research Service. “We’ve cut seed production by 99% so you no longer see the carpets of seedlings moving through the landscape the way you used to.” A series of insects – also known as biocontrols – were released beginning in 1997. To document their efficacy, Tipping and his team sprayed pesticides on a plot of melaleuca growing in a cypress-pine wetland every month for five years. Trees that were treated with pesticides to control the introduced insects were nearly 50% more dense after five years, compared to an increase of less than one percent on the unsprayed plots. Biocontrols have been used for years to control pests although some – like the cane toad imported to eat beetles in sugarcane fields – have actually become pests themselves. ARS scientists are now charged with ensuring that any biocontrols imported won’t eat other plants. “Most insects only feed on a very few plants, most often plants that are closely related to each other,” Tipping said. Other biocontrols are being released now for both lygodium and water hyacinths although it’s still too early to tell what kind of impact they might have. Some biocontrols, like a mite released to eat lygodium, don’t naturalize well for reasons scientists may never understand. Having melaleuca under control, however, means that land managers can focus on other species without having to be concerned that the melaleuca will come back. “Those big trees may live for a long time but realistically they’re no longer a threat so managers can cut them down when they get around to it.” Tipping said.

ASIAN GREEN MUSSELS

When Asian green mussels were first discovered in Tampa Bay – clogging an intake valve at TECO’s Big Bend plant – experts feared the worst. Perna viridis is the fastest-growing mussel in the world, reaching six inches in just two years with older females releasing millions of eggs when they spawn. The large and rapidly growing mussels crowd out native species on bridge pilings, docks and marine debris but they’re less likely to be seen on native substrates. “They love concrete and seem to particularly like bridges – the pilings on Gandy are 100% covered in mussels from the high tide mark down to the sediment,” notes Nancy Smith, an Eckerd College professor who has studied the mussels. “It looks like they’ll colonize any hard surface, even marine debris, but it’s rare to see them on natural substrates.” That’s not necessarily true in other locations, she adds. “You sometimes find them on seagrasses or oyster shells but I’ve never seen them on mangroves, which they apparently colonize in the Caribbean.” And while they’re still a maintenance problem at the Big Bend plant, they have not required any control beyond removing growth from equipment, according to Kevin Young, TECO’s environmental engineer. Almost nothing controls green mussels except removal, Smith said. Sheepshead – with their hard mouths and multiple rows of teeth – will sometimes eat the smaller green mussels but nothing touches the larger ones. Her students have dissected more than 1000 green mussels and found no evidence of parasites. “No predators, no parasites, so they can out-compete other species so easily.”

When Asian green mussels were first discovered in Tampa Bay – clogging an intake valve at TECO’s Big Bend plant – experts feared the worst. Perna viridis is the fastest-growing mussel in the world, reaching six inches in just two years with older females releasing millions of eggs when they spawn. The large and rapidly growing mussels crowd out native species on bridge pilings, docks and marine debris but they’re less likely to be seen on native substrates. “They love concrete and seem to particularly like bridges – the pilings on Gandy are 100% covered in mussels from the high tide mark down to the sediment,” notes Nancy Smith, an Eckerd College professor who has studied the mussels. “It looks like they’ll colonize any hard surface, even marine debris, but it’s rare to see them on natural substrates.” That’s not necessarily true in other locations, she adds. “You sometimes find them on seagrasses or oyster shells but I’ve never seen them on mangroves, which they apparently colonize in the Caribbean.” And while they’re still a maintenance problem at the Big Bend plant, they have not required any control beyond removing growth from equipment, according to Kevin Young, TECO’s environmental engineer. Almost nothing controls green mussels except removal, Smith said. Sheepshead – with their hard mouths and multiple rows of teeth – will sometimes eat the smaller green mussels but nothing touches the larger ones. Her students have dissected more than 1000 green mussels and found no evidence of parasites. “No predators, no parasites, so they can out-compete other species so easily.”

WALKING CATFISH

A catfish that could walk across dry land sent shivers through Florida when a fisherman caught one in a Broward County lake in 1967. Another voracious predator, some people predicted that it could become a dominant fish in Florida lakes. More than 40 years later, the walking catfish is still here but seldom seen. “We call it the fish that is everywhere and nowhere,” says Scott Hardin, exotic species section leader for the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission. “It has long been established in south and central Florida but rarely abundant.” Ironically, the most significant damage from walking catfish has occurred within the aquaculture industry that unintentionally unleashed it into the wild. “It slithers into culture ponds during rainy periods and lays waste to the tropical fish that are grown outside Tampa,” Hardin said.

A catfish that could walk across dry land sent shivers through Florida when a fisherman caught one in a Broward County lake in 1967. Another voracious predator, some people predicted that it could become a dominant fish in Florida lakes. More than 40 years later, the walking catfish is still here but seldom seen. “We call it the fish that is everywhere and nowhere,” says Scott Hardin, exotic species section leader for the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission. “It has long been established in south and central Florida but rarely abundant.” Ironically, the most significant damage from walking catfish has occurred within the aquaculture industry that unintentionally unleashed it into the wild. “It slithers into culture ponds during rainy periods and lays waste to the tropical fish that are grown outside Tampa,” Hardin said.

CANE TOADS

While homeowners may find it difficult to tell the difference between a Cuban tree frog and a native frog, it’s easy to recognize an adult cane toad because they’re so much larger than native species. “Anytime you see a toad bigger than four inches, you can assume it’s a bufo cane,” says Steve Johnson, an associate professor of ecology at the University of Florida. Introduced to Florida to help control pests in sugar cane fields, these toads are dangerous to small animals because they can secrete a toxin as a defense against predators. Although not dangerous to human beings, the toxin can kill a small animal that bites or licks a toad. They’re sensitive to cold and the Tampa Bay region is probably the northern tip of their range in Florida. Populations here are probably declining after two cold winters and there is some evidence that the numbers of cane toads are dropping in South Florida as well.

While homeowners may find it difficult to tell the difference between a Cuban tree frog and a native frog, it’s easy to recognize an adult cane toad because they’re so much larger than native species. “Anytime you see a toad bigger than four inches, you can assume it’s a bufo cane,” says Steve Johnson, an associate professor of ecology at the University of Florida. Introduced to Florida to help control pests in sugar cane fields, these toads are dangerous to small animals because they can secrete a toxin as a defense against predators. Although not dangerous to human beings, the toxin can kill a small animal that bites or licks a toad. They’re sensitive to cold and the Tampa Bay region is probably the northern tip of their range in Florida. Populations here are probably declining after two cold winters and there is some evidence that the numbers of cane toads are dropping in South Florida as well.

COYOTES

Coyotes, says Jeanne Murphy, a wildlife biologist in Pinellas County, are a lot like human beings. They’re extremely adaptable, they can live in almost any type of habitat, and they’ll eat almost anything. And like humans, they’re experiencing a population boom in Florida. Sightings have been documented in every Florida county and every habitat except extremely dense urban areas and the wide-open sawgrass marshes of the Everglades. Considered to be a “naturalized” and not an exotic species because fossil research indicates that they lived in Florida about two million years ago, coyotes are not the large, wolf-life predators who hunt in packs often depicted in movies. Instead they’re typically shy and relatively small – about 20 to 30 pounds – animals who moved in to fill the environmental niche left when the red wolf was extirpated and bobcats became scarce. Without predators like black bears, wolves and panthers, nothing keeps the coyote’s prey in check – and in an urban area that means rodents, squirrels, raccoons and opossums. “There is a pair of coyotes living in the area (the Florida Botanical Gardens) and we’ve noticed a much more natural level of opossums and raccoons since they’ve moved in,” Murphy said. “Coyotes are bringing back a little bit of the balance.” In more suburban settings, coyotes may prey on domestic cats or small dogs and the occasional reported sighting may just be the very tip of the iceberg, adds David Spenser, environmental specialist at Weedon Island Preserve. “Pinellas County is loaded with coyotes and we’re probably going to see a drastic increase in the future.” At least one pair has built a den at Weedon Island and several have died on roads leading to the preserve, but Spenser hasn’t seen pups yet. “I think there are too many disturbances here with the power plant construction going on.” And while coyote populations are increasing, most people will never see them, says Rob Heath, formerly wildlife biologist for Hillsborough County who now runs the non-profit Wildlife Fellowship. “We know they’re there because we continually see signs of their presence – they’re dead on the side of the road, or we see their scat or a kill site – but I very rarely see one alive.”

Coyotes, says Jeanne Murphy, a wildlife biologist in Pinellas County, are a lot like human beings. They’re extremely adaptable, they can live in almost any type of habitat, and they’ll eat almost anything. And like humans, they’re experiencing a population boom in Florida. Sightings have been documented in every Florida county and every habitat except extremely dense urban areas and the wide-open sawgrass marshes of the Everglades. Considered to be a “naturalized” and not an exotic species because fossil research indicates that they lived in Florida about two million years ago, coyotes are not the large, wolf-life predators who hunt in packs often depicted in movies. Instead they’re typically shy and relatively small – about 20 to 30 pounds – animals who moved in to fill the environmental niche left when the red wolf was extirpated and bobcats became scarce. Without predators like black bears, wolves and panthers, nothing keeps the coyote’s prey in check – and in an urban area that means rodents, squirrels, raccoons and opossums. “There is a pair of coyotes living in the area (the Florida Botanical Gardens) and we’ve noticed a much more natural level of opossums and raccoons since they’ve moved in,” Murphy said. “Coyotes are bringing back a little bit of the balance.” In more suburban settings, coyotes may prey on domestic cats or small dogs and the occasional reported sighting may just be the very tip of the iceberg, adds David Spenser, environmental specialist at Weedon Island Preserve. “Pinellas County is loaded with coyotes and we’re probably going to see a drastic increase in the future.” At least one pair has built a den at Weedon Island and several have died on roads leading to the preserve, but Spenser hasn’t seen pups yet. “I think there are too many disturbances here with the power plant construction going on.” And while coyote populations are increasing, most people will never see them, says Rob Heath, formerly wildlife biologist for Hillsborough County who now runs the non-profit Wildlife Fellowship. “We know they’re there because we continually see signs of their presence – they’re dead on the side of the road, or we see their scat or a kill site – but I very rarely see one alive.”

So What’s Growing in Your Backyard?

Most invasive plants were imported for a reason – like attractive flowers or berries, a tolerance for extremely wet or dry conditions and rapid growth patterns. But if they’re thriving in your backyard, you’re helping to maintain a seed source that can impact nearby nature preserves and wetlands. The Tampa Bay Estuary Program, working with Southwest Florida Water Management District, offers residents a series of resources to help control invasive plants in their landscapes. A field guide, available online at http://www.tbep.org/pdfs/Invasive_Plants.pdf, describes the “top 20” invasive plants in the region with color photography, in-depth descriptions, recommended control methods and appropriate Florida native plants to replace the exotic invasives. Wicked Weeds, a 21-minute documentary, takes an in-depth look at the most invasive trees, shrubs and vines in the Tampa Bay watershed. Step-by-step instructions for controlling them include an overview of safety equipment, proper use of herbicides, specific eradication techniques and directions for proper disposal of the invasive plants. It’s available by calling 727-893-2765 or via email at saveit@tbep.org.

Florida ROCs

Florida ROCs

Florida ROCs isn’t another band, it’s the newest buzzword for the various reptiles that are showing up in nature preserves (and sometimes neighborhoods) across the state. Legislation passed earlier this year bans the sale of “reptiles of concern” for personal use in Florida, including various species of pythons, anacondas and Nile monitors. While the worst of the carnivorous reptiles aren’t prevalent in Tampa Bay, there’s no reason they might not become an issue in the future. Nile monitors – lizards that may grow to seven feet and eat everything from frogs and endangered gopher tortoises to cats and small dogs – are so prevalent in Cape Coral that city officials can’t put a count on them. They’ve also been seen in Homestead and possibly Palm Beach County, and there’s no reason they can’t move further north, says the FWC’s Scott Hardin. “They have a fairly wide distribution in Africa,” he notes. The northern limit for pythons today appears to be Sarasota County, where four were spotted last year, but no one knows how well they tolerate cold temperatures. Once established, their populations could explode. Only about 60 pythons were spotted in the Everglades in 2004 – but scientists now estimate their population at up to 30,000. In the context of carnivorous reptiles, the four-foot tegu lizards that appear to be established in the Balm-Boyette area of south Hillsborough County are relatively tame. They’re much more docile and they eat roots and seeds as well as small rodents. The problem is that the smaller tegus move into the endangered gopher tortoise burrows where they may munch upon tortoise eggs as well as the other small creatures known to share the burrows.