“Hammerheads are really strange,” said Haley Amplo, a marine science-biology major with a minor in chemistry at the University of Tampa. “They have a wing strapped to their face. Why would they have that?”

Until this study, scientists had focused on sensory benefits from the hammerhead’s cephalofoil or head wing, explains Daniel Huber, associate professor of biology. The shape might be advantageous in terms of range of vision, turning radius and ability to pick up different electrical impulses as compared to other sharks. But the issue of the shark’s fluid dynamics and how they impact its evolution had been ignored.

“In this study, six hammerhead species were examined to determine if cephalofoil shape affected fluid drag during locomotion,” Huber said. “We had hypothesized that cephalofoil size and shape will influence fluid drag, and ultimately swimming performance.”

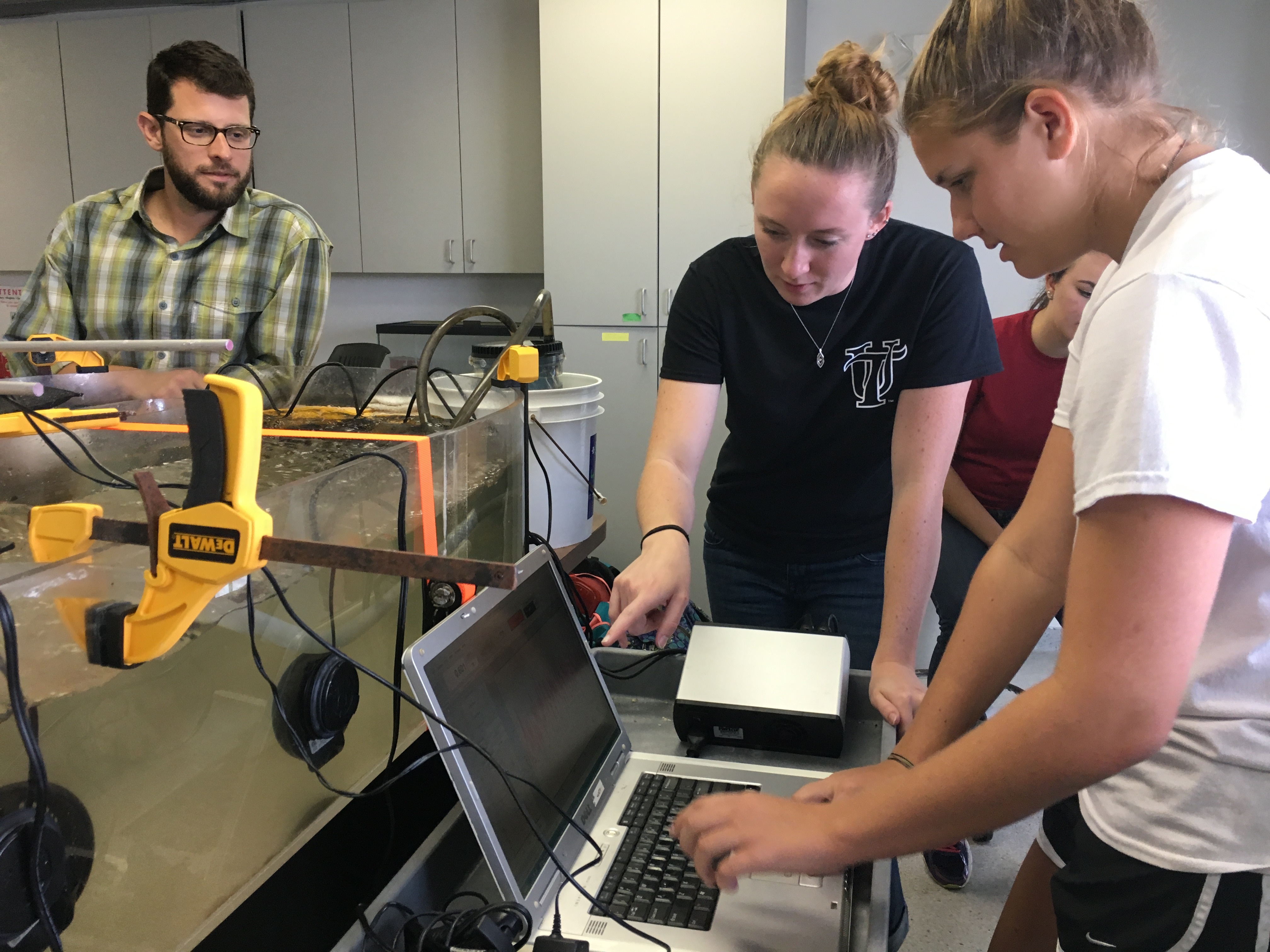

Amplo spent hours working with computer programs that read the CT scans of frozen sharks (collected from a colleague of Huber’s), cleaning up the scans in one model and using another to layer on the shark’s skeletal structure, the muscles and the skin. From there they had the data to 3-D print a shark head using the high-caliber 3-D printers through Huber’s connection at the University of South Florida’s Department of Radiology. The heads were then set up in a flume where the team including Huber, Amplo, and UT students Taylor Cunningham and Sara Casareto could take measurements of how the fluid moved around the heads at different angles.

“We’re thinking hammerhead sharks, with this huge cephalofoil, also swim at a higher angle of attack than most sharks are doing, potentially creating such a huge decrease in force or such a huge increase in lift, that that might be why cephalofoil evolved in the first place,” Amplo said. “Maybe all these sensory benefits are all secondary.”

Amplo said one of her biggest takeaways from this research project is learning how to be creative with fixes, as well as adaptable.

Amplo said one of her biggest takeaways from this research project is learning how to be creative with fixes, as well as adaptable.

“One of the big things I’ve learned from this project is that science is not this straight line. It’s a lot of troubleshooting,” she said. “I had to learn how to think like a scientist, where there’s not a lab manual in front of you telling you the steps to go by. A lot of it is problem solving on your own. Coming up with an idea when you’re in the shower and writing it down really quick because hey, that might be a good angle to come at it. You have to think outside the box and slightly differently than everyone else is thinking.”

Amplo presented her research at the Florida Undergraduate Research Conference in February, along with several other UT students, and again at the CNHS Undergraduate Research Symposium, which is part of UT’s Undergraduate Research Celebration Week. Later this summer she hopes to submit her work for publication.

“An experience like this is paramount in helping students decide if they want to pursue research as a career. Accumulating knowledge in the classroom only gets you so far in this regard,” Huber said. “Students need to experience the creative process of developing ideas and collecting/analyzing/interpreting data to know if research is right for them. It also helps students to develop the analytical skills needed to critically evaluate information and make evidence-based decisions, which is crucial to our competence as a society in this day and age.”

The hammerhead shark project will continue next semester with Cunningham taking the lead.

Originally published May 6, 2017