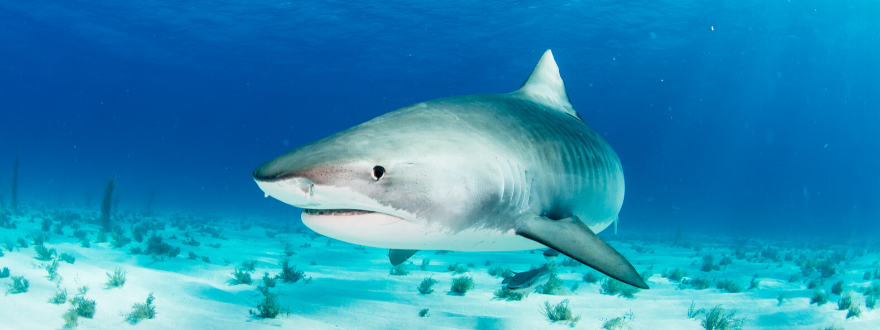

Since August, a team from the University of Tampa has been trolling the waters of Tampa Bay, intentionally sticking their hands into the mouths of sharks.

“[The first time], I was actually more scared of the bacteria in their mouths; each shark has a different personality so some are spunky and like to bite, others will just hang, so I always have to be careful not to get too used to it,” said Lilli Sutherland, who is working with Nicholas Greenberg on an undergraduate research fellowship aimed at helping Tampa Bay doctors.

Greenberg and Sutherland hope to identify the types of bacteria living in sharks’ mouths, determine what strains offer the greatest risk of infection for shark bite victims and then identify the best treatment options for shark bite victims in Tampa Bay.

“We’re both science nerds and ocean nerds,” said Greenberg, who reels the sharks in from UT’s 27-foot boat reserved for marine fieldwork. “I’m a crazy shark nerd and fisherman, so for me this was like an excuse to get out on the water. But we’re really passionate about sharks as well as medicine, so it’s a perfect project for us. It’s so fun.”

Research Combines Love for Sharks with Medicine

The fellowship, which is provided by UT’s Office of Undergraduate Research and Inquiry, gives the team funding of just under $7,000 for their year-long research project.

Greenberg and Sutherland came to UT as friends from Chicago, growing up with little exposure to marine life but having a desire to dive in and learn more. While in the lobby of Morsani Hall, they were brainstorming ideas for research projects and narrowed in on combining sharks with the medical field.

In their digging, they came across a study done by Dr. Robert Borrego, a general surgeon practicing in Palm Beach, Fla. that focused on the susceptibility of shark bacteria to antibiotics. Borrego’s research only included 20 samples of one shark species.

Greenberg and Sutherland decided to expand on Borrego’s research and include samples from several species of sharks found locally, including bull and blacktip sharks, which are responsible for 16% of attacks worldwide, according to the Florida Museum website.

When a human is bitten by a shark, pathogens and bacteria can transfer due to the severity of laceration often associated with a shark bite. Those bacteria, however, can be resistant to some antibiotics, making it difficult for health care professionals to treat shark bite victims.

Greenberg and Sutherland started pitching their idea to professors at UT in their sophomore year and found mentors in biology professors Ann Williams and Dan Huber.

“The research idea has a ton of scientific merit, but I was more impressed by the fact that they pitched an idea to Dr. Williams and me,” said Huber. “Not many students have thought through the process deeply enough to pitch an idea to their professors.”

It took a year and a half to get the necessary permissions and project set up, but by August they were out on the water.

A Day on the Boat

There’s no typical day for the team while collecting samples.

Greenberg, Sutherland, and John Ambrosio, marine science field station coordinators, depart from UT’s marine science field station. Bait is thrown into the water to attract sharks. Depending on how active the waters are, some days there is little success while others there are dozens of sharks in the water.

Once a shark takes the bait, Greenberg reels in the shark close to the edge of the boat, moving quickly to minimize shock to the shark. Ambrosio slides a mat under the shark, which is then slightly lifted out of the water by Sutherland. While the shark is held out of the water, Sutherland reaches inside its mouth with three cotton swabs to take samples.

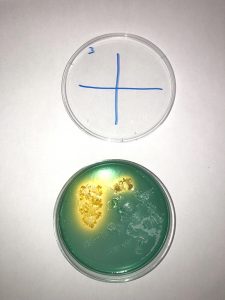

The shark is then released, and the samples are placed on individual media plates and taken back to the microbiology lab. The plates isolate bacteria the team is looking for that could be pathogenic to humans. Through several tests, they can see if pathogenic bacteria are present. The samples that are more unusual are set aside to be sent out to an off-site commercial lab for genetic testing.

“What we’re looking for is if the bacteria in the mouths of sharks is able to be treated with typical antibiotics, or do we need to tell doctors to use stronger antibiotics,” said Sutherland. “So far what we have found is that absolutely, [doctors] should be using different antibiotics, because there are crazy patterns and resistances for the bacteria [to antibiotics],” said Greenberg.

The team currently has tested 23 sharks and will likely have 30 by the time the research is finished in the early spring semester. They are planning on publishing and presenting their findings at the American Society for Microbiology conference in Chicago in June. From there, the research could go in a number of directions.

“Our hope is to publish the research, and then create a triage guide for medical professionals to be able to quickly assess threats of infection from shark-related injuries,” said Huber. “Right now, we are focused on the relationship between shark and bacterial species, but we could also investigate how these relationships change throughout the life of the sharks and how habitat affects these relationships.”

By Mallory Culhane, UT journalism major