If you’ve ever looked out the window of an airplane flying into Tampa International, you may have noticed the strange checkerboard patterns on bayside mangrove forests. It’s not aliens designing a field where they can land their spacecraft—it’s bygone technology from the 1950s.

If you’ve ever looked out the window of an airplane flying into Tampa International, you may have noticed the strange checkerboard patterns on bayside mangrove forests. It’s not aliens designing a field where they can land their spacecraft—it’s bygone technology from the 1950s.

The plan then was to control mosquitoes by digging ditches through mangrove forests where their larvae were thriving. The ditches would drain some mangrove forests, allow fish and other predators into others, or increase salinity in what otherwise would be the brackish waters most mosquitoes prefer.

Turns out, they didn’t work all that well and, in the long run, they’ve created more problems than they solved.

“The ditches weren’t dug with hydraulics in mind,” says Bruce Hasbrouck, environmental services director for Faller, Davis & Associates, Inc. “Without proper tidal flushing, the ends of the ditches get silted in and never drain, causing water quality to decline and stress the mangroves. Digging the ditches also resulted in spoil mounds — piles of dirt placed along the edge of the ditch which turned out to be the perfect spot for Brazilian pepper to grow.”

Filling them in is easier said than done. Using heavy equipment can cause major damage to the surviving mangroves. Hydroblasting, which uses a relatively small pump to blast the spoil mounds back into the ditches with pressurized water, has mixed results in terms of restoring the functions of a mangrove forest.

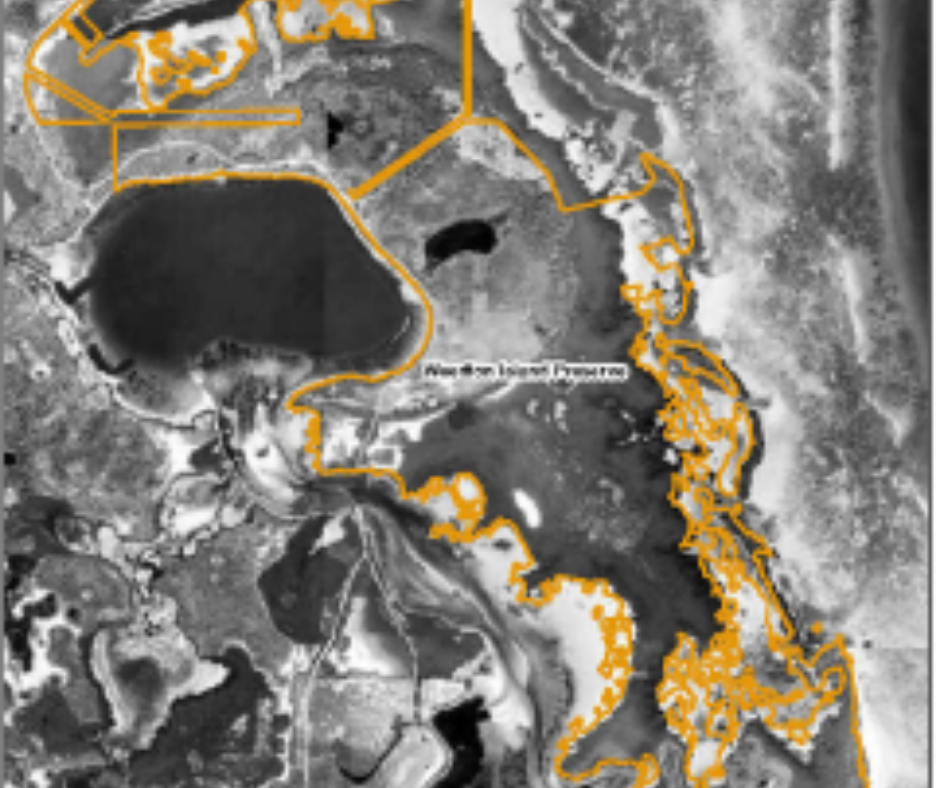

The pilot project planned at Weedon Island Nature Preserve is designed to address those challenges with a phased restoration project beginning with a 42-acre site. “We’re calling it a pilot study because part of the contract calls for us to apply lessons learned so we can use the principles that work going forward,” Hasbrouck said.

The pilot project planned at Weedon Island Nature Preserve is designed to address those challenges with a phased restoration project beginning with a 42-acre site. “We’re calling it a pilot study because part of the contract calls for us to apply lessons learned so we can use the principles that work going forward,” Hasbrouck said.

It calls for a giant amphibious machine that looks like it could have come from outer space to “walk-in, dig out,” or WIDO, flattening the spoil mounds to a level that allows tidal flows back through their historic locations. Geotubes will be used to remove silt and muck from the mosquito ditches so they flow more smoothly.

“We’re not trying to create wetlands, we want to restore them to their original function,” he said. “The best way to do that is to take them back to the way they used to be.” Finding undamaged mangrove forests as examples to mimic proved to be more difficult than expected, he adds. “They were pretty hard to find because most of them had already been ditched. We looked all over the state and finally found a few in Charlotte Harbor.”

Mangroves were ditched across Tampa Bay in the 1950s, particularly along its southeastern shores, areas north of the Courtney Campbell Causeway and the southwest section of MacDill Air Force Base. “We’ve known about the problems ditching causes, but it’s expensive to repair them although there have been some efforts beginning in the 1990s,” Hasbrouck said. “Restoration ecology is still a young science and learning through trial and error takes a while for the systems to respond to give us a chance to see what works.”

Lessons learned from Weedon will be applied as the project continues. Hasbrouck expects to publish results after the project is finished, particularly when monitoring results are available.

And, for those concerned about one of the most popular recreational features at Weedon Island: the much-beloved mangrove tunnels will be improved, not filled in, he adds. “It will be much better kayaking – there may be a small, temporary impact but the mangroves will recover in three to five years.”

Design is underway now, construction is expected to start in 2023.