“Along with an overall impact of sea level rise, we need to know if there’s a difference in how those habitats respond,” said Lindsay Cross, TBEP’s environmental science and policy manager. Some of the sites under consideration include Weedon Island and Feather Sound on the bay’s western shore, where mosquito ditching crisscrosses healthy mangroves and marshes. Recently restored sites, including Schultz Preserve and Cockroach Bay, also are being considered to ensure that planning for sea level rise works as well as scientists expect it to.

Signs of change – including mangrove encroachments into high marsh – already have been documented at the first site at Upper Tampa Bay Park, Cross said. “We didn’t expect to see changes quite this early,” she adds.

Previous studies have indicated that sea level rise will dramatically change coastal habitats in Tampa Bay, leaving bay managers to question if their long-time focus on “restoring the balance” of coastal habitats found in the 1950s is still a feasible option. In undeveloped areas with historical sea level rise — about an inch per decade — habitats simply moved inland and remain relatively balanced. In regions like Tampa Bay, where most of the coast has been developed for human use, habitats don’t have that alternative. Scientists also are concerned that habitats may not be able to move as quickly as needed in light of increases in projected sea level rise over the next 50 years.

Overall, all coastal habitat is expected to decline in the Tampa Bay by 2100, but some habitats are at significantly greater risk. Coastal freshwater wetlands are expected to show the greatest losses, and salt marsh and salt barrens also are expected to decline. The proportion of mangrove acreage will more than double – up from about 66% of habitat in the 1950s to an anticipated 96% of habitat in 2100. Loss of diversity in habitat may create a “bottleneck” for species of fish and other animals that depend upon it, including flounder, permit, redfish, sheepshead, snook, spotted seatrout and tarpon.

Overall, all coastal habitat is expected to decline in the Tampa Bay by 2100, but some habitats are at significantly greater risk. Coastal freshwater wetlands are expected to show the greatest losses, and salt marsh and salt barrens also are expected to decline. The proportion of mangrove acreage will more than double – up from about 66% of habitat in the 1950s to an anticipated 96% of habitat in 2100. Loss of diversity in habitat may create a “bottleneck” for species of fish and other animals that depend upon it, including flounder, permit, redfish, sheepshead, snook, spotted seatrout and tarpon.

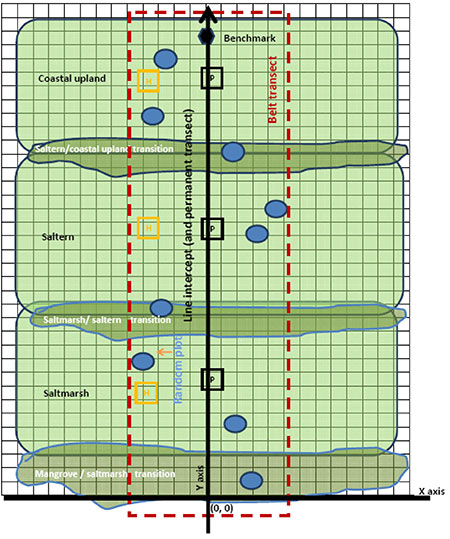

“The focus of the ‘restoring the balance’ paradigm was always to return habitat as much as possible to historic levels and proportions because the species that live in the bay have evolved to depend upon those specific plants and levels of salt in estuarine habitats,” Cross said. “These transects will help us identify the changes as they happen.”

Ironically, the biggest challenge facing Tampa Bay 30 years ago when high levels of nitrogen left it nearly devoid of life may have been easier to overcome than finding effective ways to cope with global climate change, Cross notes. “We can’t lose focus on nitrogen, but we also need to become better land managers, continuing to make progress and tweak our expanding knowledge base to deal with rising seas.”

By the Numbers

Elevation changes as tiny as an inch may determine which species of plants can live in a given location and this monitoring efforts suggest that the habitats found within an elevation zone are remarkably consistent around the bay. Data from the National Wildlife Federation suggests that a 15-inch rise in sea level will result in:

- 96% loss of tidal flats

- 86% loss of saltmarsh

- Significant loses of coastal freshwater wetlands