Additional wastewater and stormwater improvements, combined with tighter controls on dredging and filling, have continued to fuel the bay’s recovery with impressive results: the waters of Tampa Bay are as clear today as they were in 1950 and, since 1982, the bay has regained more than 6,000 acres of seagrasses, underwater nurseries vital to the survival of fish, shellfish and other marine life. Seagrasses, which generally grow in waters less than six feet deep, are an important barometer of the bay’s health because they require relatively clear water to flourish. Tampa Bay now supports 28,299 acres of seagrass, far less than the Tampa Bay Estuary Program’s goal of 38,000 acres, but the highest recorded total since the 1950s.

Sustaining these gains and advancing bay improvement will be difficult as the region continues to grow. More than three million people reside in the Tampa Bay watershed, and the region’s population is expected to double by 2050.

In this issue, the Tampa Bay Regional Planning Council’s Agency on Bay Management presents a cross-section of reports from local and state partners responsible for bay monitoring and improvement, part of its 2008 State of Tampa Bay Report.

“We hope readers gain a better understanding of what’s being done to protect the bay and become inspired to become better stewards of the estuary,” says ABM Director and senior planner Suzanne Cooper.

Established in 1985, ABM is a broad-based committee of scientists, citizens, industry and government representatives, environmentalists and fishermen. The watchdog group reviews major projects and issues impacting Tampa Bay and advocates for its protection.

ABM’s first state of the bay report was published in 1987 to inform elected officials and citizens about issues and challenges facing the Tampa Bay estuary, and agency efforts on the bay’s behalf. With the launch of Bay Soundings in 2002, the annual report was suspended to lend support to the development of a quarterly bay news journal targeting a broader audience of readers.

The State of Tampa Bay marks its return this year with the first in a series of ABM member reports beginning below. Readers are invited to contact the authors listed at the end of each report for additional information.

[su_divider]

Highlights from the Agency on Bay Management

By Robert A. “Bob” Kersteen, ABM Chair

For more than two decades, the Tampa Bay Regional Planning Council’s Agency on Bay Management has played a vital role as a watchdog and advocate for Tampa Bay. Actions by ABM have helped chart a course for the bay’s recovery by promoting water quality and habitat improvements that have led to a resurgence of underwater seagrass nurseries and fisheries. This recreational paradise is providing boundless enjoyment to boaters, anglers, residents and visitors.

Agency members are stakeholders who represent diverse interests, including commercial and recreational fishing, the environmental community, port authorities and shipping, as well as government, research and education. Issues coming before the ABM receive the full attention of this forum, ensuring thorough evaluation of projects and plans impacting Tampa Bay. Known for providing objective project review, the Agency has earned widespread respect in both the public and private sectors.

Over the past two years, the full Agency and its Executive Steering, Natural Resources/Environmental Impact Review, and Habitat Restoration committees have reviewed a wide variety of projects and issues, many of which are noted below:

WATER QUALITY:

- Hydrobiological Monitoring Program for surface water withdrawal projects and the Tampa seawater desalination plant

- Tampa Bypass Canal and Alafia River reclassification, from Class III to Class I, proposed by Tampa Bay Water. The discussion included evaluation of Mosaic Company’s present and future phosphate mining and processing operations in the watershed, as well as operation of the Hillsborough County wastewater treatment facilities.

- Nitrogen Management Consortium plans to allocate nitrogen loading to the bay in response to state and federal mandates.

DEVELOPMENT:

- Gulfstream Natural Gas Pipeline proposal involving installation of a natural gas transmission pipeline from Port Manatee to the Progress Energy’s Bartow electrical generating plant located on Weedon Island.

- Tampa Harbor General Reevaluation Study, including alternatives for channel widening and deepening to improve shipping safety and transportation.

- Piney Point closure activities. The Agency provided assistance during this multi-year effort by the Florida Department of Environmental Protection to safely close the abandoned phophogypsum stack and fertilizer manufacturing facility and end the discharge of nutrient-rich water to Bishop Harbor.

- Redevelopment of the Apollo Isles golf course and the Georgetown community for residential uses.

- Port Manatee expansion and estuarine habitat impact mitigation.

- Location of additional electrical transmission lines within the region and legislation potentially affecting local government review.

- Tampa Bay Rays’ Waterfront Baseball Park/Tropicana Field Redevelopment proposal. The Agency identified a list of studies needed to assess the environmental effects of plans for redevelopment of the existing site and development of the waterfront parcel to inform city leaders prior to city council action on the project.

- One Bay 2050 visioning process for the Tampa Bay region.

NATURAL RESOURCES:

- Seagrass management planning in Hillsborough County.

- Mangrove trimming rules in local counties.

- Clam Bayou restoration. At the request of Senator Bill Nelson, ABM held a forum to hear the various issues surrounding this small embayment of Boca Ciega Bay. A multi-phase stormwater management plan spearheaded by the Southwest Florida Water Management District, the City of St. Petersburg and the City of Gulfport is expected to significantly reduce pollution there.

- Habitat master plan for the region.

WATER USE:

- Downstream augmentation proposal by Tampa Bay Water for the Hillsborough River.

- Water supply planning for Manatee County and areas served by Tampa Bay Water.

- Minimum flows determination for the lower Alafia and the lower Hillsborough rivers.

COORDINATION:

- The need to better coordinate the process for determining mandatory Total Maximum Daily Loads for impaired waters and Minimum Flows and Levels for rivers.

- Marine law enforcement on Tampa Bay waters.

- The use of boat registration revenues for boat launch facilities.

- Cooperative Vessel Traffic Information Service in Tampa Bay.

ABM meets the second Thursday of each month at the Tampa Bay Regional Planning Council, 4000 Gateway Centre Blvd, Suite 100, in Pinellas Park. For more information, call (727) 570-5151, ext. 32.

[su_divider]

Manatee County’s Frog Creek Subject of Study

By Greg Blanchard

Frog Creek begins 9 miles east of Terra Ceia Bay near the town of Parrish in rural Manatee County at an elevation of about 35 feet above mean sea level. A watershed of about 9.5 square miles ensures that Frog Creek flows year-round. The lower reaches of the stream are tidal and transition from freshwater stream to mangrove forest near its terminus at Terra Ceia Bay.

The importance of tidal coastal tributaries to the health of the Tampa Bay estuary has long been recognized. Questions remain about how to effectively manage these areas. As part of a multi-agency study of bay area tidal tributaries conducted by the Tampa Bay Estuary Program and funded by the Pinellas County Environmental Fund, Manatee County staff collected and analyzed environmental information on Frog Creek. Results of this study are expected to be published this year by the Tampa Bay Estuary Program.

Few areas in the Tampa Bay region are immune from development pressures and the Frog Creek watershed is no exception. Development pressures north of the Manatee River are intense, and thousands of homes are planned in the area. The upper reaches of Frog Creek are channelized to improve drainage and reduce flooding. Manatee County, in cooperation with the Southwest Florida Water Management District and others are studying the drainage and flooding issues in the area. Data from this effort will also help us to manage the communities downstream.

[su_note note_color=”#d2f4e4″]The Manatee County coastline forms one of the most scenic natural borders of Tampa Bay. The area is dominated by extensive mangrove forests, luxuriant seagrass meadows, and unique coastal bays and bayous. One of the treasures of the ‘Mangrove Coast’ is a tributary of Terra Ceia Bay called Frog Creek.[/su_note]The Manatee Water Atlas has additional information on the Frog Creek watershed, including maps, aerials, reports, data, and photos. Visitors can also add their own photographs.

For additional information, call (941) 742-5980 or email greg.blanchard@mymanatee.org.

[su_divider]Tampa Bay Water Highlights From The Last 2 Years

By Bob McConnell

Tampa Bay Water plans, develops, produces and delivers high-quality wholesale drinking water to continuously meet the needs of Hillsborough County, Pasco County, Pinellas County, New Port Richey, St. Petersburg and Tampa. The non-profit, special district of the state of Florida was created by an inter-local agreement with a nine-member Board of Directors—two elected commissioners from each member county and one elected representative from each member city. More than 2.5 million residents in the tri-county area are served by its member governments.

Tampa Bay Water provides about 187 million gallons per day (mgd) to the Tampa Bay region through a diverse water supply network that includes a surface water treatment plant with river/canal and reservoir sources, a seawater desalination facility, seven groundwater treatment plants, 13 regional wellfields, and almost 200 miles of pipeline. Each of these facilities is part of the Master Water Plan, a blueprint to meet the long-term drinking water needs of the region, while meeting the Board’s goals of environmental stewardship, cost and reliability.

New Water Supply Facilities

Thanks to the public’s investment of time and money, and the efforts of our partner, American Water-Pridesa, the Tampa Bay community can take pride in the nation’s first operating, large-scale seawater desalination plant. The re-mediated Tampa Bay Seawater Desalination Plant came on-line in 2007 and adds balance and reliability as the region faces the realities of drought and climate change. When operating at full capacity, the plant provides up to 25 mgd, or 10% of the region’s drinking water supply.

Another key component of the region’s drinking water supply, the 15-billion gallon C.W. Bill Young Regional Reservoir, was completed in 2005 and began providing water to the region in 2006. Water stored in the Reservoir can be sent to Tampa Bay Water’s surface water treatment plant, and when full the Reservoir can provide 25% of the region’s water needs for six months. The Reservoir supplied more than 11 billion gallons of water for treatment and distribution in 2007.

Protecting Water at the Source

As a strong advocate for the protection of the public’s regional water resources, Tampa Bay Water is heavily involved in environmental monitoring and management activities to ensure protection of ecological resources and the quality of drinking water sources.

Clean, safe drinking water doesn’t start at the tap—it starts at the source. As the region’s drinking water supply becomes increasingly reliant on new sources of water, it’s important to protect the health and safety of those sources, the environment, and the public’s investment.

Tampa Bay Water’s ongoing source water protection activities include significant effort in two new initiatives: a new source-water protection grant program to further public awareness of the value and benefits of source protection, and petitioning the state of Florida to strengthen water quality standards in important tributaries to Tampa Bay. Protecting water quality in the Alafia River and Tampa Bypass Canal helps preserve the purity of the public’s drinking water, protects the public health, and guards the public’s $800 million investment in alternative supplies. The result will be safe, clean water for the long-term economic and public health of the region.

For more information, contact Bob McConnell at rmcconnell@tampabaywater.org or call (727) 796-2355.

[su_divider]Tampa’s Bay Study Group Continues Long-Term Monitoring Efforts

By Roger Johansson

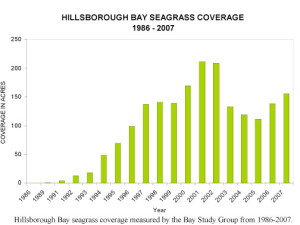

The Bay Study Group, part of the City of Tampa’s Wastewater Department, currently employs four research biologists. The group was created in 1976 to evaluate anticipated positive effects on the Tampa Bay system as the city upgraded its wastewater treatment plant from primary to advanced treatment in the late 1970s. At that time, the group initiated a comprehensive field monitoring program of water quality and biological indicator communities in Hillsborough Bay and other bay segments. Today, much of its activities involves the continuation of long-term efforts begun more than three decades ago. These programs assess: (1) ambient water quality, (2) phytoplankton biomass, taxonomic composition, primary production (14C-method), and community nutrient limitations, (3) macro-algae (sea weed) composition and biomass, and (4) selected benthos distribution and abundance.

Several research and monitoring studies have been added to the program since its inception to ensure early detection and documentation of changing bay conditions. Submerged seagrass research and monitoring was added about five years after the city upgraded its wastewater treatment plant, after seagrasses had started to colonize the shallow areas around Hillsborough Bay. Because seagrasses are highly sensitive to water quality conditions, they are an excellent indicator of the overall health of the bay system. Seagrass coverage has increased substantially in Hillsborough Bay over the last 20 years, indicating that the bay is improving.

In other areas, particularly upper Tampa Bay, seagrass recovery is lagging. The Bay Study Group has joined other agencies over the last several years in conducting three major research studies to investigate the causes of the problem:

- The Feather Sound study (2003 through 2007) involved extensive water quality characterization and seagrass research in the central sections of Old Tampa Bay. The study partners concluded that water quality may be limiting seagrass expansion in the southwestern section of Old Tampa Bay.

- The Middle Tampa Bay seagrass transplanting study near MacDill AFB (2006 to present) has introduced manatee grass to the area and has also evaluated bottom elevation dynamics associated with the plantings. Results to date indicate that the planted manatee grass is established and may have caused limited sediment accumulation.

- The recently initiated development of a bio-optical model for Tampa Bay. This work will analyze how water quality constituents in shallow bay waters affect the quantity and quality of light transmitted through the water. The ambient light information will then be related to the specific light requirements of seagrass species found in the bay to help explain and predict patterns of seagrass abundance and distribution. The model will be an useful tool to aid in bay seagrass management efforts.

Over the last 30 years, the Bay Study Group has had the privilege to witness and report on a remarkable restoration of water quality and biological communities in Hillsborough Bay and Tampa Bay as a whole. These improvements have garnered worldwide recognition for Tampa Bay as a case study of successful estuarine management and restoration.

For more information, contact Roger Johansson at (813) 247-3451 ext. 237 or emailroger.johansson@ci.tampa.fl.us.

[su_divider]Manatee Protection In Tampa Bay

By Nanette O’Hara

The increasing number of manatees using Tampa Bay – especially in the winter, when upwards of 350 manatees gather near warm-water power plant outfalls – has led to the creation of an extensive network of manatee protection zones to reduce the potential for watercraft collisions with these “gentle giants.”

Slow speed zones have been established throughout the bay by either county ordinance or state rule. The zones are mostly in shallow waters harboring seagrass beds where manatees feed and rest. Additionally, two no-entry areas have been created, around outfalls at TECO’s Big Bend plant in Apollo Beach and Progress Energy’s Bartow facility at Weedon Island. These areas are important winter refuges for manatees.

In addition to participating in review and development of manatee protection zones, the Tampa Bay Estuary Program’s Manatee Awareness Coalition (MAC) has initiated innovative boater education programs to promote compliance with the speed zones. The MAC is a partnership of scientists, bay managers, environmentalists, boaters, the marine industry and utilities. Among these accomplishments:

The “Bay-Friendly Boater’’ program provides customized kits to boaters new to boating in general, or just new to boating in Tampa Bay. The kits contain a variety of information about boating safety and etiquette, as well as important natural resources such as manatees and seagrasses.

Navigation software produced by Garmin is the first to feature manatee and homeland security zones in Tampa Bay, thanks to a partnership between Garmin, the MAC and the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission. Boaters using the updated electronic charts will see manatee zone boundaries highlighted as they scroll over portions of Tampa Bay where slow speed zones have been established, such as Old Tampa Bay, and the Manatee River. Homeland security zones also are displayed on the chart plotters.

The “Minute for Manatees” program trained instructors with the Coast Guard Auxiliary to incorporate brief tips about manatee-friendly boating in their popular Safe Boating Courses, expanding the reach of this important information to new boaters.

Manatee deaths due to watercraft strikes in Florida in 2007 were lower than the previous 5-year average. Tampa Bay has averaged about 10 manatee deaths due to watercraft in the past 5 years. That this number has remained stable despite the dramatic increase in the number of boaters using Tampa Bay (there are more than 126,000 registered boats in the 3-county area) is a positive sign, and is likely the result of both regulatory action and expanded boater education.

For more information, contact Nanette O’Hara at (727) 893-2765 or email Nanette@tbep.org.

[su_divider]

Tampa Bay Watch Taps Volunteers for Habitat Restoration

By Rachel Arndt and Peter Clark

Tampa Bay Watch, Inc. is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit stewardship program dedicated exclusively to the charitable and scientific purpose of protecting and restoring the marine and wetland environments of the Tampa Bay estuary. Each year, Tampa Bay Watch involves more than 10,000 youth and adult volunteers in hands-on habitat restoration projects. Following are highlights of our program accomplishments in 2006 and 2007:

Salt Marsh Restoration

In 2006, 624 community volunteers planted 55,400 plugs to restore 12 acres of salt marsh. Tampa Bay Watch helped to coordinate the largest one-day planting ever, on September 29, 2007, with 350 volunteers planting 34,000 salt marsh grasses over 32 acres of newly-constructed wetland habitat in northern Manatee county. In 2007, 670 community volunteers planted 53,830 plugs to restore 11 acres of salt marsh at the Manatee Viewing Center; Little Bird Key NWR; MacDill AFB SE shoreline; Shultz Nature Preserve and Whale Island NWR.

Bay Grasses in Classes school wetland nursery program

Salt marsh wetland nurseries have been established at 18 schools in Pinellas and Hillsborough Counties, monitored and maintained by students of all ages. The nurseries provide a source of native wetland plants for use in habitat restoration projects. The program also provides students with valuable hands-on experience in habitat restoration activities while promoting science education and the value of maintaining a healthy environment. After 6-8 months of growth, the students participate in a harvesting-transplanting event where a portion of their nursery will be removed and planted with the help of community volunteers at a coastal restoration site in the Tampa Bay area. In 2006, 9,000 students planted 55,050 plugs to restore 24 acres of salt marsh. In 2007, 3,200 students planted 34,000 plugs to restore 18 acres of salt marsh through the BGIC.

Additionally, Campbell Park Elementary School started to grow Spartina bakerii, a high salt marsh plant, as a pilot program for storm water pond restoration.

Community Oyster Reef Enhancement (CORE) Programs

Oyster domes are placed along seawalls and shorelines to restore hard bottom habitat, improve water quality and reduce shoreline erosion. In 2006, 860 students and volunteers invested 2,600 hours to construct 1,400 domes which were placed on 1,800 linear feet of shoreline. In 2007, 857 oyster domes were installed at Bayshore Blvd. and Mac Dill Air Force Base.

Oyster shell reefs improve water quality, restore hard bottom and provide habitat for fish and wildlife resources. In 2006, 990 volunteers invested 2,730 hours to build oyster bars on 2,300 linear feet of shoreline at six different locations in the bay. The CORE Oyster Bar program successfully built 1,250 feet of oyster reef during 2007 using 97 tons of fossilized shell. Project site locations included Ft. DeSoto, MacDill Air Force Base, Andrew’s Island (Suncoast Seabird Sanctuary) and Weedon Island Preserve. A total of 370 volunteers participated in these events over 11 work days, totaling 1,330 volunteer hours.

Monofilament Recycling Stations

Monofilament fishing line is a serious threat to birds and other wildlife. In 2006, 210 volunteers participated in eight island cleanups to recover 22,900 feet of monofilament line with 220 pounds of line recycled per month. In 2007, Tampa Bay Watch maintained 86 monofilament recycling tubes in 42 locations throughout Pinellas County and Hillsborough County. Over 100 pounds of monofilament line was cleaned and recycled. Additionally, over 2 miles of fishing line was recovered by 78 volunteers during the 14th Annual Monofilament Clean-Up held October 20th.

Derelict Crab Trap Removal

In Tampa Bay, it is estimated that there are thousands of abandoned crab traps that have been accumulating in the bay for decades. Tampa Bay Watch performs aerial surveys to identify these derelict traps and conducts clean-ups to remove them. Removing the derelict traps reduces unnecessary by-catch of marine organisms, eliminates marine debris, and potential safety hazards to boaters. The program also helps to expand public awareness of the problem and provide a community-based opportunity to enhance Tampa Bay. In 2006, Tampa Bay Watch led eight trap removal events to remove 350 derelict traps with the assistance of 55 volunteers. In 2007, the program identified and removed 32 derelict crab traps from the waters of Tampa Bay with the assistance of community volunteers and the Florida Airboat Association.

Tampa Bay Estuary EDventures Education Programs

Tampa Bay Watch Marine Education Center features outdoor wet labs, touch tanks, and aquariums, all of which are utilized for education about Tampa Bay and restoring its marine habitats for school field trips by bay area schools, summer camps and community groups. Education programs build environmental literacy and encourage stewardship while educating students about estuarine science and habitat restoration through a combination of classroom curriculum and field experience. In 2006, 1,800 students were educated about the Tampa Bay estuary through the marine science center and outreach, 144 students completed two summer camp sessions and 31 field trips were conducted through the marine science center.

In 2007, 3,120 students were educated about the Tampa Bay estuary through the marine science center and outreach, 120 campers experienced five summer camp sessions of Estuary EDventures and 106 field trips were conducted through the marine science center.

For additional information, contact Tampa Bay Watch at 727-867-8166.

[su_divider]Longshore Bar Restoration To Aid Seagrass Recovery

By Lindsay Cross

Longshore bars associated with seagrass meadows historically existed throughout Tampa Bay, but have decreased by nearly half their 1940s total length. Scientists hypothesize that disappearance of longshore bars, which may dampen wind- and ship-generated wave energy, contributed to seagrass declines in Tampa Bay.

The Longshore Bar project is a multi-partner, collaborative effort. Tasks completed to date include:

- Mapped current and historical distribution of bars to determine losses in total bar lengths since 1940s.

- Characterized topography/bathymetry of existing bars in relationship to seagrass distribution.

- Developed a conceptual model of a restored seagrass longshore bar system.

- Developed coastal engineering criteria for reconstruction of bars using dredged material.

- Prepared an Environmental Resource Permit application for all project aspects.

Measurements of natural and man-made waves at locations with and without bars are on-going. Instruments were installed onshore and offshore of a submerged bar at Coffeepot Bayou in spring 2008. Water flowed faster inshore of the bar, probably because there is a similar volume of water flowing through a shallower area. Results from deployment at the MacDill area will be available this summer.

Seagrass transplants of manatee grass (Syringodium filiforme) and turtle grass (Thalassia testudinum) were conducted in summer 2006 using volunteers. 18-month monitoring shows complete recovery at donor locations and growth and coalescence of patches at the transplant location. This work will help determine whether transplanted grasses will naturally accumulate sediments, thus creating a bar.

An experimental bar system, consisting of four 100-foot bars, will be constructed south of MacDill peninsula in the fall of 2008. This work will test an engineered bar system’s integrity over time and track establishment of seagrasses both seaward and landward of the structures. Four materials will be considered for the experimental bars:

- Rubble-sized rip-rap material

- Sand covered with filter fabric and overlaid with river rock or gravel

- Two 15’ diameter Geo-tubes filled with previously dredged material

- One 15’ diameter Geo-tube filled with previously dredged material with filter fabric and overlaid with smaller rock, sand and shell material.

Monitoring the establishment of volunteer seagrass and survival of planted seagrasses for five years will be conducted for all project components.

For more information, contact Lindsay Cross at the Tampa Bay Estuary Program at (727) 893-2765 or email Lindsay@tbep.org.

[su_divider]Estuary Program Studies Tidal Tributaries

By Ed Sherwood

Tidal tributaries within the Tampa Bay estuary encompass a collection of system types that vary based on their size, salinity, range and proximity to Tampa Bay. Some have a complete estuarine salinity gradient ranging from fresh to saline, while others are entirely subject to the circulation of adjacent bay and riverine waters. These systems include coastal and riverine creeks with and without direct freshwater input, dredged inlets, and other backwaters. Collectively, these tidal tributaries have received far less monitoring than other larger systems in Tampa Bay.

In 2003, Tampa Bay scientists and managers identified assessing the importance of tidal tributaries as the top-ranked research need in supporting the Tampa Bay Estuary Program’s Comprehensive Conservation and Management Plan. As a result, the TBEP embarked on a research project funded by the Pinellas County Environmental Fund, in cooperation with the various federal, state and local partners. Major tasks of the project included:

- characterizing the fisheries resources of Tampa Bay tidal tributaries

- determining the effects of various habitat parameters (e.g., watershed condition, water quality, structural habitat, etc.) on fisheries

- developing measurable goals, management recommendations, and a tidal management strategy based on study results, and

- communicating results to managers and the public to support informed decision-making about their preservation or restoration.

Four preliminary management actions were identified as a result of the research conducted during this project. These actions will be further refined with additional input from Tampa Bay managers and scientists and include:

- Maintaining connectivity between open bay waters, tidal rivers and smaller, tidal tributaries to allow fish movement, water flow and nutrient flux between these backwaters and larger estuarine areas

- Reducing “flashiness” of water flow to tidal tributaries to promote natural flow patterns and foster the productivity of fish food sources within these systems

- Tracking the condition of fish nursery functions and physical water quality parameters in additional backwaters to further assess the uniqueness of Tampa Bay tidal tributaries

- Improving public education and stewardship of tidal tributaries by promoting the importance of these systems as key habitats to estuarine fish species such as snook.

For more information, contact Ed Sherwood at (727) 893-2765 or esherwood@tbep.org.

[su_divider]Investigation Uncovers Leaking Sewer Pipes At Ben T. Davis Beach

By Byron Bartlett

The waters off Ben T. Davis Beach on the Courtney Campbell Causeway have long been plagued with high bacteria counts leading to numerous beach closings. Historically, the cause was attributed to pollution in stormwater runoff.

Recognizing the need to locate and mitigate possible sources, the Health Department engaged USF microbiologist Dr. Valerie Harwood and obtained a grant from the Environmental Protection Commission’s (EPC) Pollution Recovery fund. Dr. Harwood’s work on microbial source tracking was able to demonstrate that fecal contamination from human sources was responsible for the high bacterial levels on at least some occasions.

In April 2007, the EPC joined the effort to help identify the sources of contamination and located a damaged 8-inch sewage main discharging to the Bay near the east end of Rocky Point. Staff from the City of Tampa’s Department of Sanitary Sewers quickly responded and repaired the main. However, beach closings continued when additional sampling continued to show the presence of bacteria from human waste. Additional investigations conducted in cooperation with the city suggested that an old 4-inch sewage main on the south side of the causeway may have been leaking into the bay from a stormwater ditch. The city promptly replaced the main.

The partnership between the Health Department, USF, the City of Tampa and the EPC resulted in the location of several possible sources of pollution. City repairs, along with minor repairs at two local restaurants, have prevented several thousand gallons a day of sewage from entering the bay, eliminating potential health risks to beachgoers.

As monitoring continues, local officials are hopeful that improved water quality will eliminate the need for beach closings this summer.

For additional information, contact Byron Bartlett at (813) 627-2600 ext 1018 or email Bartlett@epchc.org.

[su_divider]Originally published Summer 2008