By Victoria Parsons

From a perfectly straight-forward perspective, lawn fertilizer in Florida is a pretty good value. For about $25, the average homeowner can sprinkle enough nutrients, pesticides and weed killer to keep their lawn bright green and weed-free for several months.

The real price tag is much higher. In fact, that $25 worth of fertilizer, applied incorrectly, could easily cost thousands of dollars:

- The average cost to remove a single pound of nitrogen that washes into stormwater is $9080, according to reports compiled by the Florida Department of Environmental Protection.

- Phosphorous, although less commonly found in turfgrass blends, is even more expensive to remove – at an average cost of more than $30,000 per pound.

- Local governments are operating under an agreement with state and federal regulators to strictly limit the amount of nitrogen released into Tampa Bay. If nitrogen levels increase, growth could be stifled, causing an unknown financial impact to the region.

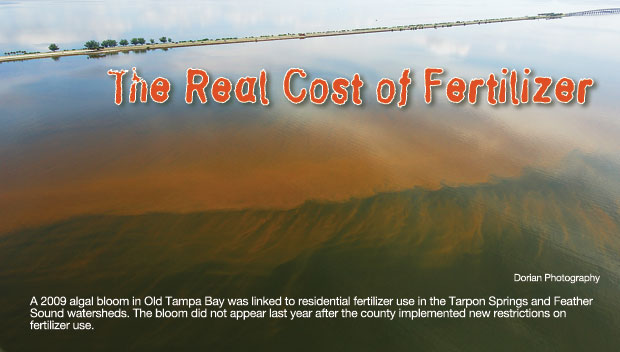

Even without regulation, excess nutrients can cost the region dollars and jobs. In Tampa Bay, too much nitrogen fuels the growth of algae that blocks sunlight that seagrasses need to grow. Animals ranging from fish and crabs to birds and manatees need seagrasses to survive, so their populations can decline. The algae can also form large blooms, clouding the water and making Tampa Bay less appealing for swimming, boating and other activities. Recreational and commercial fisheries, as well as the ecotourism industry, would suffer.

And while the link is less clear, many scientists believe that excess nitrogen in the Gulf of Mexico intensifies and prolongs growth of the toxic algae that causes red tide. By some estimates, the 2005 red tide cost Pinellas County $240 million in lost tourism revenues.

Cutting Back on Fertilizer

Nearly 50 cities and counties in Florida have implemented local ordinances that reduce fertilizer in stormwater as regulations at both the state and national level kick in. In the Tampa Bay watershed, a consortium of more than 40 governments and industry operate under a unique agreement that limits nitrogen loading on a voluntary basis. (See Bay Soundings, Winter 2011)

The agreement, however, limits nitrogen loadings to the current level – which means that new businesses or development cannot move forward unless another permit holder cuts back.

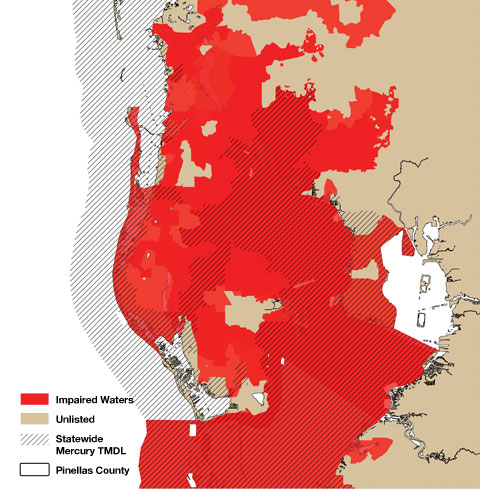

And while Tampa Bay is showing clear signs of improvement, more than half of its watershed is still considered “impaired,” with levels of nutrients, bacteria and dissolved oxygen below state standards. In Pinellas, the most densely populated county in the state, more than 80% of waters fail to meet current state standards.

Recognizing the problem, Pinellas County voted to implement the state’s most stringent fertilizer regulations in 2010. Retailers are limited to carrying fertilizers with at least 50% slow-release nitrogen from October to May 31 and nitrogen- and phosphorus-free products from June to September.

“We’re 98% built out and the majority of our land use is residential,” says Pinellas County Commissioner Susan Latvala. “We have no heavy industry, no major agriculture, very few septic tanks and all our wastewater facilities are already using AWT (advanced wastewater treatment) – there’s nowhere else for us to cut nitrogen except residential sources like fertilizer.”

Even at just a 50% compliance rate, managers estimate that the new ordinance will prevent about 27 tons of nitrogen a year from entering stormwater systems in Pinellas County alone. With the average cost of removing it pegged at $9080 per pound, potential savings to the county could reach $490 million – nearly one-third of the total $1.6 million county budget for 2011.

“It’s a no-brainer,” says Latvala. “We can’t raise taxes enough to pay for (nitrogen reduction) but we can’t thumb our nose at the regulations either.”

A series of studies in Tampa Bay directly link residential fertilizer to degraded water, adds Kelli Levy, watershed division manager for Pinellas County.

• A study of nutrients in groundwater in the Lake Tarpon watershed shows that 79% of the nitrogen entering the lake through groundwater is from fertilizer

• The Old Tampa Bay/Safety Harbor study links “increased, inorganic fertilizer sources” to significantly impaired water quality

• In Joe’s Creek, a nutrient source tracking study using isotopes suggests that fertilizers are a primary source of nitrogen in the watershed

• The Klosterman Bayou tracking study also indicates that excess fertilizer use is degrading both surface and ground water.

Formal studies that measure the actual impact of fertilizer ordinances are just in their infancy. One study, in Michigan’s Huron River watershed, showed a 31% drop in phosphorus concentrations (the regulated nutrient in that region) in the first year, with an additional 17% drop the following year. Closer to home, the city of Venice in Sarasota County also saw significant drops in phosphorous and nitrogen, as well as an increase in dissolved oxygen, after a 2007 ordinance.

Although it’s still too early to draw correlations between reductions in nutrient levels and the fertilizer ordinance, nitrogen levels in most Pinellas watersheds did drop last year. In Old Tampa Bay, where water quality consistently lags the rest of the bay and algal blooms have been a regular phenomenon, chlorophyll-a concentrations dropped by 40%.

Tampa Bay Estuary Program expects to start a formal assessment of water quality improvements following the passage of fertilizer ordinances later this year. Of the three counties bordering the bay, Pinellas has the most stringent regulations, Hillsborough bans the use of fertilizer within 10 feet of a waterway and Manatee has not yet addressed the issue.

Legislature Looks at Local Ordinances

When Sarasota County began to consider limiting nitrogen use during the summer rainy season in 2007, detractors said it would put people out of jobs, kill lawns and destroy the county’s market for high-end homes. “I made a commitment, right up front, that if it didn’t work, we’d go back in and fix it,” recalls Jon Thaxton, the commissioner who led the effort that ultimately resulted in a unanimous vote by the commission.

Four years later, lawns are as lush and verdant as ever and the furor has pretty much died down – at least in Sarasota County. As Bay Soundings goes to press in early April, state legislators are considering a bill that would restrict the right of counties to pass fertilizer ordinances stronger than the state’s model ordinance. “It’s a draconian one-size-fits-all measure that sends mixed messages,” says Thaxton. “They tell us it’s our job to clean our waters but then take away one of the best tools we have.”

Fertilizer ordinances are not a silver bullet that removes all nitrogen, but they are one of the least expensive options for counties faced with meeting stringent new regulations at both the state and national level, Thaxton said.

Even discounting the dollar savings, most people do not want to cause pollution that leads to dead fish on beaches or lakes covered in algae, adds Latvala. “People want to do the right thing, most of them just don’t know how harmful fertilizer can be if it’s used incorrectly.”

What’s In Fertilizer?

What’s In Fertilizer?

Most gardeners know that fertilizer contains three major ingredients, identified in large letters on the front of the package. Commonly abbreviated as N-P-K, they describe how much nitrogen, phosphate and potash (or potassium) is included in the fertilizer.

Water managers look at these ingredients from the perspective of “limiting growth” in an aquatic environment. In Tampa Bay and most marine ecosystems, the growth of algae is limited by the availability of nitrogen. When nitrogen levels remain near those that are found in a natural setting, algae are a balanced part of the underwater food web.

But if nitrogen levels increase – from fertilizer, wastewater and industrial plants, atmospheric deposition or even animal waste – algae grow more quickly and upset the natural balance. Along with clouding water so that sun is blocked from seagrasses, algae consumes high levels of oxygen as it decays, often causing massive fish kills in summer months.

In most freshwater ecosystems, phosphorus is the limiting factor that controls the rampant growth of algae. In Central Florida – known as Bone Valley for its rich phosphate deposits – and in most of the Tampa Bay region, phosphorus is less an issue because the natural levels already are so high.

Potassium, or potash, is the third number in the fertilizer formula. It is less damaging in aquatic environments so it’s often found in “summer blends.” In lawns and landscapes, potassium boosts root growth and tolerance to heat, cold, drought and foot traffic. It’s less likely than nitrogen to cause growth spurts that attract insects and require more frequent mowing.

Two so-called “minor ingredients” support the growth of a healthy lawn without damaging aquatic ecosystems. Iron and sulfur both promote bright green, dense turf. Look for them in summer blends and high-quality turfgrass formulas — they are not as likely to be included in less-expensive fertilizer blends.

Additional tips on Florida-friendly fertilization practices from the Southwest Florida Water Management District:

- Always use slow-release fertilizers

- Always follow package directions

- Fertilize when the grass is actively growing

- Never fertilize before a heavy rain

- Leave a 10-foot buffer zone between fertilized areas and nearby water

- Never leave fertilizer on sidewalks or driveways – sweep it up and put it back in the bag.

Save money and prevent run-off by measuring your yard – excluding landscape plants – before buying fertilizer. If your lawn is a simple square or rectangle, multiply the length and width in feet to determine square footage. If it’s an irregular shape, estimate its size as a rectangle and use those measurements to calculate its size.

For more information, visit www.watermatters.org

Originally published Spring 2011