by Victoria Parsons

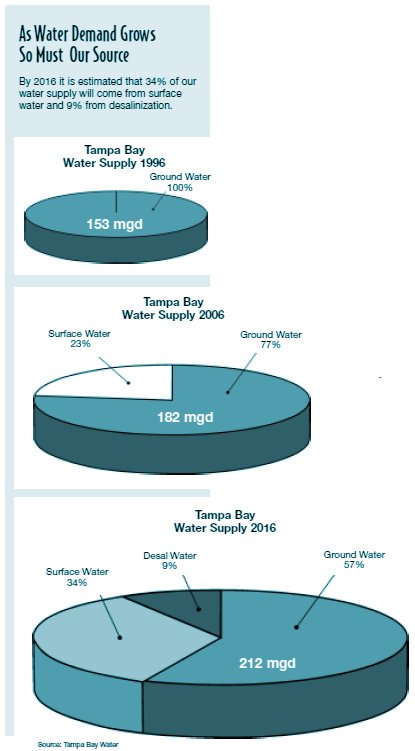

As 1997 dawned in Tampa Bay, nearly two million people relied primarily upon the Floridan Aquifer for their drinking water. Increased water use in the rapidly growing region – combined with an ongoing drought – resulted in shrinking lakes, vanishing wetlands, dried-up wells, a surplus of sinkholes and finger-pointing between local governments that degenerated into water wars. Even the Miami Herald took note of Tampa Bay’s problems in a front page story proclaiming “Water Woes Threaten State’s Future.”

Water woes made front-page headlines again in January 2007, with yet another drought causing officials to call for mandatory cutbacks, but there’s a little more water in the glass this year. Instead of local governments fighting over well fields, the state’s largest regional water supplier was created in 1998 to take responsibility for filling spigots across the region. Instead of relying entirely on groundwater, more than 11 billion gallons of surface water, are now stored in a south Hillsborough reservoir. In fact, the reservoir has been so successful that plans are being developed to expand its use to serve the growing region’s water needs through 2017.

But the glass is still only half full. The much-anticipated $157-million desal plant in Apollo Beach – the largest in North America – may or may not come online in March, more than three years after its originally scheduled opening. Managers say it will contribute an average of 17 million gallons per day (mgd) to the region’s water supply by the end of this year, when groundwater pumping must be reduced to 90 mgd from 113.45 withdrawn last year, but skeptics abound.

And continued growth means growing demand, anticipated at 138.4 mgd or a 45% increase between 2000 and 2025 in the four counties that make up the Tampa Bay watershed.

A Long and Winding Road

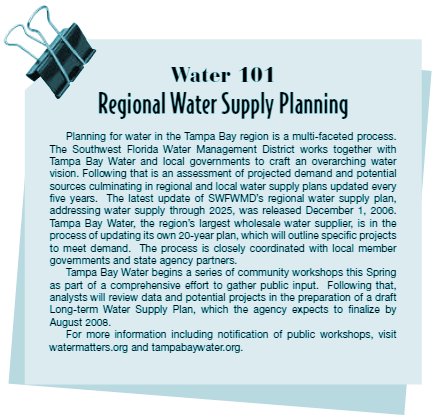

2007 also marks the start of another round of planning for Tampa Bay Water, the organization responsible for supplying water to local governments serving two million customers in Hillsborough, Pinellas and Pasco counties. Its plan will provide details on specific projects, dates and funding sources addressing demand projections presented in the Southwest Florida Water Management District’s regional water supply plan draft completed in December 2006.

2007 also marks the start of another round of planning for Tampa Bay Water, the organization responsible for supplying water to local governments serving two million customers in Hillsborough, Pinellas and Pasco counties. Its plan will provide details on specific projects, dates and funding sources addressing demand projections presented in the Southwest Florida Water Management District’s regional water supply plan draft completed in December 2006.

Across the region, the long-term goal is to reduce reliance on groundwater and rivers, both of which have caused significant environmental harm. In Southwest Florida, including Tampa Bay, offstream reservoirs, built to store water harvested from rivers at high flow, may be a key part of the solution to the region’s water problems.

By tweaking current permits and expanding the delivery capacity of the C.W. Bill Young Regional Reservoir, TBW expects to create an additional 8.3 mgd per day to serve the region through 2017. “It would require an expansion of our surface water treatment and pumping facilities, but the reservoir will handle a three-fold increase just by using it more often,” said Jerry Maxwell, TBW executive director.

After that, a second regional reservoir is being considered to serve increased needs through 2025, most likely built on land adjacent to the first reservoir in Lithia. The initial concept calls for water to be harvest-ed from the Alafia River, at mid to high flows.

At least through 2017, the plan is to harvest water from the Hillsborough River and Tampa Bypass Canal only when the rivers are high and at least 100 cubic feet per second is flowing over the dam near Rowlett Park. That plan has the support of organizations like Tampa Bay Estuary Program and Agency on Bay Management which protested when TBW had suggested using highly treated wastewater to augment downstream flows while harvesting water above the dam.

“It’s a significant paradigm shift from where we started 150 years ago – when we just sunk a well or built an instream reservoir – until we saw that they caused unacceptable harm,” notes Dave Moore, SWFWMD executive director. “Capturing floodwater is going to be a real workhorse for Tampa Bay and west central Florida and I feel pretty good about moving forward for decades to come with environmentally sustainable supplies.”

But the process has not been easy. In fact, the plans on the drawing board only slightly resemble those proposed nine years ago. The desal plant, designed to provide a drought-proof source of water — up to 25 mgd or 10% of the region’s demand in 2003 — has yet to come on line. A brackish water desal plant planned for Pinellas County is on the drawing board but construction is years and possibly decades away. Plans like recapturing up to 5 mgd wastewater from an industrial source in Plant City also are on hold because the reservoir expansion is so promising.

The sources coming online now were originally planned in 1998 when TBW started with a list of more than 300 potential projects, and narrowed it down over two years of public workshops and planning sessions. “Going through the public hearings and technical permitting is a very long process, but it’s really valuable because we have the opportunity to talk to people and deliberately look and listen to their input,” Maxwell notes.

Final projects “very seldom are built exactly as planned,” he adds. “What rou-tinely happens is that we go into a meeting to look at a project and we end up explor-ing new ideas that often are better.”

Public input in a series of workshops, specifically from the Tampa Bay Estuary Program and Agency on Bay Management, was critical in shaping the current plans for expanding the use of the reservoir – which not only provides a cost-effective source of new water but is expected to help reduce nutrient loadings to Tampa Bay from stormwater runoff.

In another instance, TBW moved a surface water treatment plant from Thonotosassa to a brownfield off Faulkenburg Road. “One person came to a meeting in Thonotosassa and said that his community was always the dumping ground, and then suggested another site -an old steel plant on Faulkenburg Road that was properly zoned,” Maxwell said. “It was a brownfield, but the board gave us the freedom to clean it up and it’s a far superior site to the one we had planned originally.”

And no idea is ever too far out to be considered, he adds. “Every suggestion gets our attention – what doesn’t work today might be feasible in 20 years.” Some ideas that aren’t quite ready for prime time: a giant dehumidifier to collect water from the air, tapping into freshwater springs in the Gulf of Mexico and having melting ice-bergs delivered in tanker ships.

Protecting the Source

Protecting the Source

As an ever-increasing percentage of the region’s potable water is harvested from local rivers, protecting the quantity and quality of those sources becomes more critical. Growing populations demand larger amounts of clean water, but traditional development practices both squander water and contribute to water pollution.

For decades, the focus has been to move water off land as quickly possible, minimizing the potential for flooding. More recently, as environmental managers have recognized the contributions of contaminants in stormwater runoff, regulations have dictated stormwater controls, typically large retention or detention ponds. While the ponds are effective at collecting sediments, they are far less effective at removing nutrients. As a result, both the volume and contaminant levels in stormwater runoff from developed parcels has continued to increase.

The Florida Department of Environmental Protection is working with water management districts this year to revise the state stormwater rule to promote low impact development principles. “Water quality is going to be a huge issue for us,” Maxwell said. “We’re working with local governments to protect those water sources and we’ve openly advocated for variances (that would allow low-impact development) in some cases.”

Increasing awareness about seemingly innocent actions, such as overuse of fertilizers and pesticides, also will be important. “Protecting the environment and our water supply have a lot in common,” says Paula Dye, TBW project manager.

Water Use Caution Area

While developing environmentally sustainable water is important everywhere in Florida, the situation is even more critical in the Southern Water Use Caution Area (SWUCA), established in 1992 to minimize the impact of saltwater intrusion. Across the 5,100-square-mile SWUCA, which includes much of southern Hillsborough County and stretches south to Charlotte County, nearly 6,000 wells are lowering water levels in lakes and rivers and allowing saltwater to intrude into the aquifer. In the Tampa Bay watershed, the region’s most rapid growth is occurring in the SWUCA, including South Shore near Apollo Beach and the northern segments of Manatee County.

Residents in Manatee and parts of Sarasota County currently rely on water from an instream reservoir in the Manatee River which eventually enters lower Tampa Bay. The 7.5-billion-gallon reservoir is expected to serve Manatee County residents through 2014. After that, they’ll become part of the Peace River/Manasota Water Authority, modeled after Tampa Bay Water, to supply increased demand as populations grow. The authoritys’ six-billion-gallon offstream reservoir in southern DeSoto County, expected to open in 2008, won Audubon of Florida’s first-ever award recognizing an alternative water supply project. When complete, it is designed to be filled with water taken from the Peace River during periods of high flow and to supply water to the authority’s service area for a full year without any additional withdrawals.

“The project will take pressure off coastal area groundwater and estuaries and help the environment,” said Eric Draper, Audubon policy director.

“We’re a growing region and need access to water, but we’re not going to do anything to degrade the environment,” said Ray Pilon, governmental affairs coordinator for the water authority. “The reservoir is a very good solution.”

Tampa Bay Shines in Conservation

One area in which the Tampa Bay region shines is conservation. Average per capita water use here is 95 to 115 gallons per day – compared to over 170 gallons in South Florida. TBW estimates that its customers saved the equivalent of 18 mgd in 2005 and are on target to save 31 mgd by 2010.

“I serve on two national boards and Florida clearly leads the nation in water conservation,” Moore adds. “Tampa Bay and Sarasota/Manatee are probably as good as anywhere it gets in the country –we do more recycling than anyone, more conservation and more low-volume retro-fits.”

That success goes back several decades, when salt water first began to intrude in the aquifers under Pinellas County. While the City of St. Petersburg and county purchased wellfields in Pasco and Hillsborough counties – the first strike in what later became the water wars – they also promoted conservation.

That success goes back several decades, when salt water first began to intrude in the aquifers under Pinellas County. While the City of St. Petersburg and county purchased wellfields in Pasco and Hillsborough counties – the first strike in what later became the water wars – they also promoted conservation.

Even so, there’s absolutely more room for improvement, particularly with out-door use, notes Dave Bracciano, demand management coordinator for TBW. Most new homes built to updated codes could be slightly more water-efficient inside, he said, but very few landscapes are designed to conserve water – and up to half of all water in the region is used outside.

New building ordinances in some counties, implemented during the last drought in 2001, call for more efficient irrigation systems but they’re not necessarily inspected to ensure that they’re installed correctly, he adds. “We need to treat landscaping and irrigation systems like plumbing or electrical systems, and have trained inspectors on the job to ensure that they’re installed right the first time,” Bracciano says.

Although many older homes don’t have automatic irrigation systems, 70% of new homes have them. Fast-growing Pasco County passed an ordinance in 2002 requiring that no more than 50% of a yard be irrigated; a similar change in Sarasota County helped reduce per capita water consumption by 40%. In Hillsborough’s booming South Shore district, peak water use continues to grow, reflecting the number of new homes with new irrigation systems.

In most cases, Bracciano says, home-owners set and forget those systems so they run whether the landscape needs it or not. New technology, scheduled to be field test-ed in Pinellas this year, may help by sensing water levels in the soil and turning sprinklers on only when they’re really needed. And people who say established lawns are dying with once-a-week watering have a problem with their irrigation system, not the watering restrictions, Bracciano says. “Once a week watering is as much water as an established landscape needs.”

Reuse on the Rise

In the esoteric world of statistics, reusing water counts toward conservation because per capita use is measured by the amount of new water consumed. Florida recently won a Water Efficiency Leader Award from the US Environmental Protection Agency for water reuse saying that the program was “a model for efficient use of water” with 41% of wastewater treated for reuse on lawns, golf courses and parks.

In Tampa Bay, reuse is a more complicated issue. Highly treated effluent from wastewater plants flows into the bay, carrying nutrients but also providing a flow of fresh water into the estuary that could be used to create low-salinity habitat vitally important to dozens of species of fish and shellfish.

Across the region, approximately 115 million gallons of wastewater are reused daily — about 55% of available wastewater— and the numbers are rising. The City of Tampa’s STAR — South Tampa Advanced Reuse — project has provided piping in west and south Tampa to deliver reclaimed water to more than 7000 residents and businesses in south Tampa, saving over 3.2 mgd of water during dry season. Expanding STAR further could cost up to$30 million but provide another 4 mgd of reclaimed water. An even larger project, linking Tampa’s wastewater treatment plant on McKay Bay to the Pasco County line, could provide more than 28 mgd, conserving approximately 18.7 mgd of drinking water.

Across the region, approximately 115 million gallons of wastewater are reused daily — about 55% of available wastewater— and the numbers are rising. The City of Tampa’s STAR — South Tampa Advanced Reuse — project has provided piping in west and south Tampa to deliver reclaimed water to more than 7000 residents and businesses in south Tampa, saving over 3.2 mgd of water during dry season. Expanding STAR further could cost up to$30 million but provide another 4 mgd of reclaimed water. An even larger project, linking Tampa’s wastewater treatment plant on McKay Bay to the Pasco County line, could provide more than 28 mgd, conserving approximately 18.7 mgd of drinking water.

In Hillsborough County, the WISE —Water Infrastructure and Supply Enhancement – program is expected to increase beneficial use of reclaimed water from 50 to 100% of wastewater in the South Central system. “Our future is to be a zero discharge utility,” said Bart Weiss, administrator of the county’s water resource team.

Pinellas was one of the first counties in the nation to embrace water reuse with the South Cross Bayou Treatment Plant coming on line in 1965. County officials report that the reclaimed water system can accommodate growth through 2020.

Murphy’s Desal Plant

Its full name is the Tampa Bay Seawater Desalination Plant, but considering its history, it could have been named for Edward A. Murphy, the Air Force officer who penned Murphy’s Law.

Even before construction got under-way, things began going wrong. A partner in the consortium that was to design, build and operate the plant went bankrupt. Coventa Energy was hired, but it went bankrupt in 2002 and created a subsidiary to continue building the plant.

Two months after opening in March 2003, seriously fouled membranes in the reverse-osmosis unit forced the plant to shut down. Coventa blamed Asian green mussels growing in the intake pipes; TBW said the problem was an ineffective pre-treatment system. Finally, when the Coventa subsidiary went bankrupt, TBW took full ownership of the plant and signed a $29 million contract to have it repaired and running by October 2006. That dead-line was pushed to December and then pushed back again until March 30 because some pumps rusted out.

As might be expected, costs have increased as well. Originally budgeted for $110 million, the plant will actually cost more than $150 million with legal costs estimated at $6 million. Operating costs, including increased filtration at the front end, are expected to be higher than originally projected. SWFWMD, which is pitching in $85 million in an effort to help TBW minimize groundwater pumping, will release the funds once the plant is operating successfully.

A Look Ahead

Whatever happens with desal, experts agree, we’re in much better shape today than we were 10 years ago. The low-hanging fruit — easy, inexpensive sources of water — already has been picked and we must continue to reduce reliance on groundwater as population and demand for water continue to grow. The offstream reservoirs planned in south Hillsborough and DeSoto counties appear to offer a cost-effective, environmentally sustainable alternative to groundwater for the next 20 years or so.

Regional water systems in both Tampa Bay and Manasota now coordinate new sources of water. The 1990s water wars erupted, in large part, because St. Petersburg and Pinellas County purchased wellfields in Pasco and Hillsborough counties and had permits to withdraw water. By 1975, the impact of nearly unregulated pumping was clear enough that a regional water authority was formed but it lacked the power necessary to develop new sources of water.

“Members could buy in when they wanted water, but didn’t have to,” Maxwell explains. “It really wasn’t until 1998 that we had a meaningful water supply authority that required members to get 100% of their water from us.” Creating the region-al water supply authority enabled the construction of facilities like the reservoir and the desal plant would have been cost-prohibitive for a single county.

And while the region is in much better shape today than 10 years ago, many challenges remain. With tens of thousands of new residents moving into the region each year, public education will be important to promote an appreciation of the value of water and its wise use. Ensuring an adequate water supply into the future also will require real growth management, including rethinking how we develop and redevelop the Tampa Bay area.

Completed in March 2005 and filled during the rainy season that year, the C.W. Bill Young Regional Reservoir in south Hillsborough County can provide 25% of the region’s water needs for six months. Pumping modifications at the reservoir are expected to provide enough new water to meet increased demands through 2017. After that, a second reservoir may be built on adjacent land. To fill the reservoir, water is piped from the Alafia and Hillsborough rivers and the Tampa Bypass Canal during high flows. Two miles long and one mile wide, the reservoir holds 15 billion gallons — 33 times the volume of Raymond James Stadium.

Photo courtesy Tampa Bay Water

For more information visit www.watermatters.org and www.tampabaywater.org.