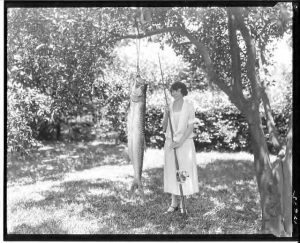

Photo courtesy Hillsborough County Public Library, Burgert Brothers Collection

As bay managers working with the Tampa Bay Estuary Program wrap up the 2020 version of the Habitat Master Plan, we thought it would be interesting to go back and look at changes in Tampa Bay over the past 200 or so years.

The original habitat master plan focused on “restoring the balance” of ecosystems found in Tampa Bay during the 1950s before significant development took place within the watershed. The newest plan takes climate change and sea-level rise into account and creates numeric targets for multiple habitats including the original seagrasses, mangroves, salt marsh, and salt barrens.

The 2020 plan also will have new goals for oyster reefs, hard and live bottom, tidal flats, tidal tributaries, freshwater wetlands, coastal uplands, and man-made habitats such as artificial reefs and living shorelines. (See http://baysoundings.com/revisiting-the-paradigm-climate-change-forces-managers-to-review-a-20-year-old-model/ for more information on the plan which should be completed early next year.)

For a historical perspective, we went to the Tampa Bay Water Atlas for a report from the Environmental Protection Commission of Hillsborough County. It’s a fascinating read that draws upon books and reports dating back to 1757.

Looking Back at Tampa Bay

The first report was written by a pilot in the Spanish Royal Fleet describing what is believed to be the original exploration of Florida’s west coast. Freshwater, of course, was a critical concern to voyagers who never knew when they would find more of it. He describes the Hillsborough River as “water is fresh and very delicate in taste.”

The next report, written in 1853 by an English soldier stationed at Fort Brooke during the Mexican-American War, called Tampa “one of the most healthy and salubrious (locations) in Florida.

“They have game in abundance, herds of deer roam through the plains and glades and crop their luxuriant herbage; numerous flocks of wild turkeys roost in the hammocks at night, and feed in the openings and pine barrens by day; and in the creeks and bays of the sea coast, or in the large freshwater lakes of the interior, incredible quantities of delicious fish are easily caught.

“Going down at low water, it was no hard task to collect as many oysters as the whole of two companies could consume.”

Resources too Vast to Imagine

In fact, that may have been the tip of the iceberg. Ernie Estevez, from Mote Marine Laboratory, produced a report extrapolating oyster populations from underwater deposits mined for construction in the 1960s and ‘70s as well as middens left by Indians. He used that data to estimate that, prior to the 1950s, an area of bay bottom of over three square miles of Tampa Bay was covered in 16 feet of oyster shells, although it raised many additional questions about the habitats and conditions that existed when the shell was deposited.

By 1880, Florida was well on its way to becoming a tourist destination. Sylvia Sunshine, a nom d’ plume for Abbie M. Brooks, wrote “Petals Plucked from Sunny Climes” promoting Florida. Her first description of Tampa, however, would not attract many people: “Roaches as long as your little finger look at us as if meditating a fierce attack, which, if executed, must result in our annihilation.”

Photo courtesy Hillsborough County Public Library, Burgert Brothers Collection

Apparently, she didn’t see any cockroaches on Egmont Key and loved it there. “No part of the world furnishes a greater variety of the finny tribe than this coast… Sharks, sixteen or eighteen feet in length, make their appearance in company with devilfish of enormous size. Jewfish, weighing three or four hundred pounds, together with tarpons of one hundred and fifty or two hundred pounds, are quite common.”

Tampa Bay Becomes a Tourist Destination

In turn, that incredible wildlife brought hunters and fishermen from across the country. G.O. Shields traveled across the country documenting places with abundant harvests, publishing his findings in 1883. The light-keeper at Egmont Key, he writes, regularly visited Mullet Key, where he had killed 193 deer in the last two years.

His descriptions of the bay are more enticing. “Without any exaggeration, there were solid acres (of mullet) so close together as they could possibly swim. This story may sound ‘fishy’ but every word of it can be corroborated by a dozen people who live in the vicinity.”

He describes multiple days of fishing, concluding that “I shall never forget this day’s sport, no matter what other rich or varied sports I may enjoy in the future.”

Those sentiments were echoed by Trench Townsend, writing a report on wildlife in Florida published in 1875. “In all these counties, the hammocks are still almost impenetrable jungles, the haunt of wild beasts, reptiles, insects, and innumerable birds, some of brilliant plumage and beautiful song, while the rivers and estuaries teem with fish which fall a far easier pray to the sportsman than do the larger game.”

In 1876, Charles Hallock’s “Camplife in Florida” describes the Hillsborough River as “fair trout fishing can be obtained and about the docks and in the channel, passable sheepshead will be found. By taking a row or sailboat, and proceeding to the oyster bay, nine miles down the bay, superior sheepshead and drum fishing can be enjoyed.”

Fisheries Decline Begins

Some of the first reports of a fisheries decline in Tampa Bay came in an 1887 report by A.C. Adams and W.C. Kendall that followed the livelihood of a mullet fisherman on Tampa Bay. “In 1874 he salted 150 barrels of mullet. Fish were very plentiful then and there was a good demand for them. In 1876 he put up 130 barrels; that year fish were not so abundant. In 1877 he packed 50 barrels; fish were scarce that year. In 1878 he also put up 50 barrels; during that year fish were a little more plentiful than in previous years. In 1879 he only packed 25 barrels; fish were very scarce and demand was limited.”

The final report in the EPCHC document is a poignant plea for restoration. Written in 1897 by a former Chesapeake Bay oysterman reporting to the U.S. Fish Commission, the report, titled “Oyster Bars of the West Coast of Florida: Their Depletion and Restoration,” is online and definitely worth the read for anyone who loves Tampa Bay.

A. Smaltz had first visited the region in 1876 and wrote: “On every hand, I found these immense reefs and beds of oysters in such seemingly inexhaustible supplies.”

By 1897, he realized that growing populations had wiped out those far-ranging reefs. “When the tide of immigration set in, and the sparsely settled communities became thriving villages and mere hamlets became splendid cities, and in the place of the Indian’s canoe and the early settler’s bateau, came the sloops, schooners, steamers, railroads and even the ocean steamers, demanding these oysters to distribute.”

Smaltz called upon the Fisheries Congress (now the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration) to immediately began restoring the oyster reefs. “They will realize that all these things are being exhausted, so far as the natural supply goes, and also realize that something must be done, and at once, in order to preserve these bounteous natural gifts so lavishly poured out by nature’s hand.

“The fact is, the natural oyster bars are a magnificent inheritance that has cost us nothing, and we are not only using but abusing nature’s providence by the most extravagant wastefulness and improvidence, and it is only by the education of the masses along these lines that we may hope for success in the restoration of our depleted oyster bars and sponge fisheries.”

Photo courtesy Hillsborough County Public Library, Burgert Brothers Collection

His plea not only went unheeded at the time, but it wasn’t long before developers began actively destroying the habitat to create waterfront property. Dredging bay bottom to fill in shallow waters began as early as 1902 and ran for nearly 75 years, literally changing the shape of Tampa Bay. Davis Islands and Tampa’s first airport were built on oyster beds. Across the bay, marshes along Salt Creek became the Bayboro district and sand dredged from Tampa Bay were upended to become North Shore.

Before dredge-and-fill operations were halted, nearly half of Tampa Bay’s shoreline had been altered by dredging, canals and causeways. However, the1970 federal court denial of a Boca Ciega Bay dredge-and-fill development set a national precedent to protect bay bottom habitats.

Moving Forward

About the same time as the courts stopped dredge and fill operations, local organizations were formed to protect the bay from further habitat losses and to improve water quality. A major turning point occurred in 1987 when the Florida Legislature created the SWIM — Surface Water Improvement and Management program — and made Tampa Bay a priority body of water. Since then, SWIM has restored over 13,000 acres of freshwater, estuarine, and upland habitat.

Over the last 50 years, coordination among private citizens, volunteer organizations, government agencies, and the scientific community has been so successful that Tampa Bay is now recognized as one of the few urban estuaries in the world where water quality and habitats are improving.

The 2020 Habitat Master Plan is designed to take that success story even further by focusing on multiple types of habitats and moving up the bay’s rivers, tributaries and coastal uplands to protect those vulnerable areas as sea-level rise threatens lower-lying portions of the bay’s ecosystems.

“We’re developing an updated plan that emphasizes restoration in more of the watershed as the next logical step,” said Gary Raulerson, the TBEP ecologist charged with coordinating the Habitat Master Plan.

[su_divider]