Few restoration initiatives have made this much difference in just 35 years: 384 projects to improve water quality, creating 15,596 acres of habitat that drains 230,725 acres of watershed.

SWIM – the Southwest Florida Water Management District’s (District’s) Surface Water Improvement and Management program – started small but has become a major player in Tampa Bay’s restoration with award-winning restorations such as the Fred and Ida Schultz Preserve, Rock Ponds Ecosystem Restoration Project and Cockroach Bay Nature Preserve, all part of a corridor of protected lands along Tampa Bay’s eastern shore.

SWIM was created by the legislature in 1987 with the Tampa Bay Regional Planning Council’s Agency on Bay Management encouraging statewide support for the five water management districts to address water quality issues including the designation of Tampa Bay as its priority waterbody. Over the years, SWIM habitat restoration projects have been implemented across most of the state, with SWFWMD expanding its efforts to cover 12 water bodies within its 16-county jurisdiction.

“The first restoration project we ever did was very small, maybe just over an acre, and all we did was plantings,” said Vivianna Bendixson, SWIM program manager. “Since then, our projects have grown more complex with hundreds of acres of restoration and the design and planning that go into making them successful.”

Dashboard Highlights Successes, Ways to Improve

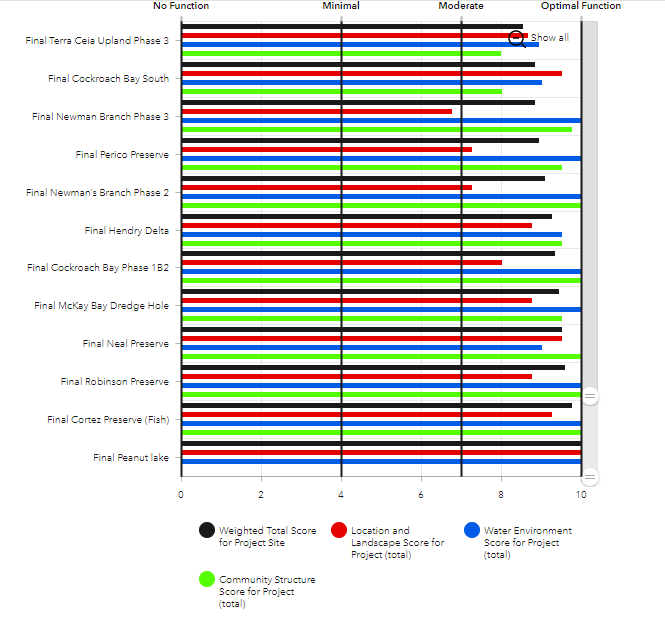

Along with celebrating their 35th anniversary, SWIM officials are creating a dashboard of all 384 projects to determine what worked best and what could be improved upon. “The plan is to visit every site every four years and score their ecological impact using standardized criteria,” said Mark Walton, a SWIM senior environmental scientist.

More than 80 habitat restoration sites in the Tampa Bay watershed were ranked last year, including Clam Bayou Nature Preserve in Gulfport, a 170-acre multi-year project that ultimately improved water quality in stormwater runoff from a 2,600-acre watershed, and Cockroach Bay, one of the largest, most complex coastal ecosystem restoration projects ever developed for the Tampa Bay estuary.

Using iPads with embedded links to pull up the original plans, staff conduct an on-site assessment to document the changes on a scale of one to ten. Water quality, including surface water flows, aquatic habitat zones and erosion, is measured. Vegetation, including the status of native plantings as well as any invasive exotics and the overall health of the plantings, also is ranked along with “edge impacts” that connect to natural lands or developments.

“We go in and look at the different kinds of habitats – open water, low marsh or higher uplands – and compare that to what we had planted onsite,” Walton said. “We evaluate the designs and management and look at where we need to follow up. Each site has a story to tell and it’s all in one place on the dashboard.”

So far, the biggest lesson learned has been that shoreline restorations may need additional buffers, or protected zones around the restored habitats to lessen the impacts of nearby human activity, Bendixson said. “It isn’t a surprise that buffers can help the longevity of the project but we’re not necessarily considering buffers now. I do think that’s something that is likely to change in the future, so we’ll look around a project and see what else could be influencing it that might impact its success.”

There are plans to make the dashboard publicly accessible in the future but for now the results are shared with the other organizations and partners responsible for maintenance of the completed projects.

Looking Forward

With most of the coastal properties surrounding Tampa Bay either restored or developed, SWIM is looking inland for habitat and water quality projects that impact the bay’s tributaries. The largest to date is the Little Manatee River Corridor with nearly 7,400 acres already in public hands, purchased by the District and Hillsborough County over the past 30 years.

New to the drawing board is Cypress Creek Nature Preserve, once at the center of the region’s “water wars.” Currently, the 7,400-acre site is owned by the District but managed by Tampa Bay Water which continues to pump potable water. Feasibility studies are underway to evaluate the potential of future restoration efforts that enhance habitat and filter nutrients near the wellfields that are largely recovered from overpumping.

Also on the drawing board: updates to SWIM’s master plans for Tampa Bay and Lake Tarpon, design and permitting at Frog Creek and parts of the Little Manatee corridor, and construction is underway at the Kracker Avenue site in an innovative partnership that is focused on providing low-salinity habitat for juvenile fish.