By Lara Milligan, Pinellas County Natural Resources Agent

I would be willing to bet that if I asked you to draw the water cycle, it would include some trees, perhaps mountains or hills, a beautiful river, some farmland, and maybe even some snow, depending upon where you come from. After all, this is how we learned the water cycle. Some water cycles will include a sprinkling of industrial buildings like a power plant or small city, but guess what just about every water cycle image is missing? People.

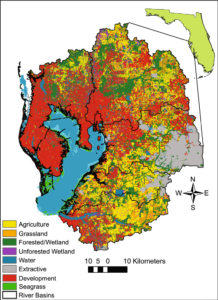

The Tampa Bay watershed is home to over three million people. The majority of this area is classified as urban/suburban, and most urbanization falls along the coast. So, if we are teaching the water cycle within the Tampa Bay watershed, it’s vital we teach how the urban water cycle works. That includes people and our daily interactions with water.

In the traditional water cycle, rain falls to the ground and infiltrates or percolates into the aquifer. However, that’s not the route water takes when it falls in the developed regions that cover most of the watershed.

Project Learning Tree produced an activity I love called Water Wonders, where participants are transformed into water molecules and go on a unique journey through the water cycle. While I have your attention, I would like to do the same with you right now.

Poof, consider yourself a water molecule. You have just fallen from a storm over downtown Tampa. Your first stop — Amalie Arena. It’s a hard landing, followed by a swift ride along Channelside Drive, then a quick drop down a dark,damp storm drain. Before you know it, you find yourself floating through Hillsborough Bay.

Phew, now you’re chilling and relaxing when all the sudden, you’re yanked up in a massive crowd into the Tampa Bay Seawater Desalination Plant. You’re tossed and turned, you’re squeezed, you’re cleaned, you’re mixed with chemicals, squeezed some more, and scrubbed clean before being shipped through hundreds of miles of old, dark pipelines before you’re spit out into the brilliant light of day through someone’s tap.

Here, you’re slathered with soap and sent back down the dark hole with an army of germs and bacteria. You again travel miles and miles of dark pipelines, and end up at the South Cross Bayou Advanced Water Reclamation Facility, also known as our wastewater treatment plant. Your journey doesn’t end here, but I won’t go on because A) it gets very technical here and B) it’s a lot.

Hopefully, you recognize that the journey I just took you on is not the water cycle our kids experience in school. It’s time to bridge the gap between the water cycle we were taught and the water cycle we experience and come to appreciate what I like to refer to as our “water story.” This is a concept I teach in my three-month, intensive course called the Florida Waters Stewardship Program (FWSP). In this course, participants explore state, regional and local water resources, focusing on watershed basics, impacts of changing waterscapes, water laws and policies, future water supply and emerging issues and more. We accomplish this through lectures, guest speakers, field tours, online explorations, class discussions, civic engagement and stewardship projects.

I encourage participants of FWSP to ask themselves three questions when they see water: 1) Where did that water come from? 2) What is happening to it? 3) Where does it go? Our key messages: With water, everything goes somewhere, and everything is connected to everything else.

A key water story all of us experience, especially in the rainy season, is the story of stormwater – in other words, rainwater produced by a storm. The word “stormwater” is often combined with the term “runoff” to form “stormwater runoff,”which is often depicted in images of the water cycle. If runoff is represented, it’s usually water running off from a natural area into a river, lake or ocean. Yet again , that’s not really the experience for most of our water. Dare I poof you into a water molecule again? I won’t, but we do need to explore the complexities of stormwater.

We saw the devastating impacts of stormwater in Sarasota back in June. Now, that was an extreme rain event, but in developed areas when even typical rain comes, it’s not falling on the green grass typically portrayed in the water cycle. It’s falling on roofs, driveways, parking lots and roadways, collecting in massive quantities and flowing rapidly to drainage areas (storm drains and stormwater ponds).

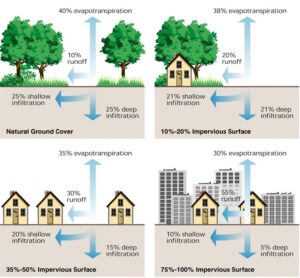

The fact that we live in an urbanized community means that there’s a lot more water to run off. A USDA report shows a significant increase in the amount of runoff during a storm in developed areas versus natural areas. For example, in a natural area there would be about 10% of water running off across the landscape during a storm event. In a developed area, that jumps to 55%. Let’s take a look at a 100,000 square foot parking lot and do the math together, keeping in mind that one inch of rain is equal to about 0.6 gallons of water per square foot.

If our parking lot receives 1 inch of rain, we will have 60,000 gallons of water with 33,000 gallons (55% or about 470 rain barrels worth) of runoff. The rest is lost to evaporation, and a small percentage can infiltrate. If we take this same rain event and put it over a natural area, we are only looking at 6,000 gallons (10% or about 86 rain barrels worth) of runoff. How we change the environment can significantly alter the journey water takes.

Some residents pay a “stormwater fee” or what Pinellas County calls a “surface water assessment.” If you’re unsure, check your property tax bill. The City of Pinellas Park explains the fees well, “Stormwater fees support costs directly related to functions of a Stormwater Management Program. Revenues collected from the stormwater fee allow the City to plan, operate, and maintain Pinellas Park’s stormwater system, which includes stormwater pipes, manholes, outfalls, catch basins, ditches, canals and storm drains. These functions support the Clean Water Act of 1972 and help control flooding, enhance water quality, and minimize the environmental impact of stormwater pollution.”

It costs a lot to manage all of that stormwater through various forms of infrastructure and associated human resources.

When rain hits our roads, parking lots and roofs, it quite literally hits the ground running, wherever gravity takes it. This can cause multiple problems, particularly in terms of water quality. According to the Tampa Bay Estuary Program, stormwater runoff is the leading cause of pollution in Tampa Bay. As it runs across yards, parking lots, roads and industrial sites, rain picks up fertilizer, litter, grass clippings, dog waste, petroleum products and other contaminants. It also can cause erosion, which can lead to sedimentation.

While we have separate pipes for wastewater and stormwater in Florida, pipes in some areas are very old – particularly those serving older communities near our coasts. Cracks and crevices in these pipes allow rainwater to creep in, further overwhelming our wastewater systems. To top it off, during the summer months, those surfaces get really hot, reaching upwards of 130 degrees. So, as the water travels along these burning hot surfaces they are warming up too, which can impact the overall temperatures of the receiving body of water.

Although it sounds overwhelming, fear not – there are many simple things we can do to lessen our impacts to stormwater challenges. Here are a few ideas to get you started:

- Don’t let your runoff run off

- Ensure downspouts are pointed so water flows into your yard instead of down your driveway. This allows stormwater to infiltrate into the soil instead of becoming runoff.

- Find an area of your yard that holds water and consider planting a rain garden. Any vegetation you plant will be helpful in slowing the flow of stormwater and providing a chance for it to filter into the soil.

- Fertilize correctly

- Fertilize only when needed (when your plants show signs of stress) and ensure you read the label so you are applying proper amounts to limit fertilizer runoff to our waterways. Clean up your yard waste too – it releases nutrients and sediments in stormwater.

- Pick up waste

- Be sure to bring a baggy with you and pick up after your pet. Pet waste is not a part of our natural environment or our waterways.

- Pick up any litter or trash on your walks or participate in an organized clean up event.

- Actively participate

- Participate in water conversations by attending public meetings.

- Educate others on what you’ve learned in this article and learn more on the Naturally Florida stormwater podcast episode.

- Get involved! There are numerous opportunities in local communities. In Pinellas County, check out Adopt-A-Pond program, the Florida-Friendly Landscaping™ Incentives Program, Adopt-A-Drain, and Storm Drain Marking Programs. Learn more about Hillsborough, Pasco and Manatee extension services by visiting their websites.

What’s most important is we do something – big or small – to improve our water resources, whether that’s minimizing fertilizer, picking up pet waste, joining your HOA pond committee to advocate for your stormwater pond, or getting plugged in with a local environmental organization. Every action we take to support our local water resources is a step in the right direction. We all can make a difference by taking action, speaking up and getting involved.

Originally published July 19, 2024