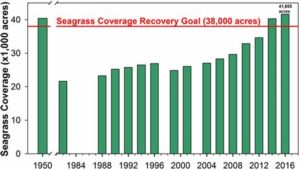

To the typical estuarine manager, Ed Sherwood has one of the best jobs in the world. As the new director of the Tampa Bay Estuary Program, he presides over an agency that has accomplished the ambitious goal set in 1995 – restoring 38,000 acres of seagrasses to near 1950s level. Tampa Bay also is enviable as one of the few large urban estuaries in the US that now meets water quality standards set for nutrients after decades of non-attainment.

But with seagrasses rebounding and many baywide actions improving water quality so dramatically, Sherwood is looking to build on those successes by setting new goals focused on other important coastal habitats and fisheries once prolific in Tampa Bay. Restoring populations of the elusive scallop to harvestable levels and rebuilding oyster beds to continually filter bay water and increase recreational opportunities for these species is now a realistic goal considering the Bay’s current “healthy” state, he said.

“It’s not unreasonable,” he says of scallop harvesting. “Look at Pasco County where the recreational harvest of scallops is open this summer for the first time since the early 1990s.” Scallops are particularly challenging because they are short-lived, and young spat are often recruited from counties further north where scallop season stretches for months rather than Pasco’s nine-day trial later this summer.

“Having Pasco waters open this year actually will make it harder for Tampa Bay because there is the chance that most adults will be harvested before they have a chance to spawn and potentially contribute spat to Tampa Bay,” Sherwood said.

Oysters, on the other hand, are “conditionally approved” for recreational harvesting in several limited areas near the mouth of the bay, as long as it hasn’t rained. “Heavy rains for prolonged periods will cause the state to close the areas for harvest.”

While scallops may be a more attractive recreational opportunity, a single oyster filters between a 2 and 10 liters (a half-gallon to 2.5 gallons) of water per hour, depending on size and water temperature.

Historically, they were found in many areas where water quality is still most challenging, including Old Tampa Bay where the potentially toxic dinoflagellate Pyrodinium has caused algal blooms most summers since 2008.

To better understand the benefits of oyster restoration in the Bay, the Tampa Bay Environmental Restoration Fund (a public-private partnership between TBEP and Restore America’s Estuaries) is working with the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission to see if shellfish species, including oysters, can filter out Pyrodinium from the water column. Otherwise, this alga produces resting cysts that can remain dormant in sediment for many years sustaining summertime blooms in the future.

“Several historic NOAA and USFWS surveys noted public and private oyster leases in Old Tampa Bay and the Rocky Point area, and we’ll continue to target those areas for restoration efforts,” he said. “The challenge with oysters is that they must have sufficient rocky or shelly bottom to grow – they can’t settle in sediments alone.”

The goals – which may not be accomplished for decades – are likely to be included in a new Habitat Master Plan scheduled for completion in late 2019. It follows the approval last year of 2017 Comprehensive Conservation and Management Plan for Tampa Bay that details work efforts until 2027.

“Holding the Line”

Tampa Bay’s initial turnaround was largely attributed to improvements and upgrades at wastewater treatment plants in the cities of St. Petersburg and Tampa. For example, the construction of the Howard F. Curren Advanced Wastewater Treatment Plant in 1979 greatly improved treatment of a major sewage discharge into Tampa Bay. Since the 1990s, the TBEP’s goal has been “holding the line” on nitrogen discharges, even as the region’s population is anticipated to grow 1.8% in 2018 to over 3.1 million people.

Tampa Bay’s initial turnaround was largely attributed to improvements and upgrades at wastewater treatment plants in the cities of St. Petersburg and Tampa. For example, the construction of the Howard F. Curren Advanced Wastewater Treatment Plant in 1979 greatly improved treatment of a major sewage discharge into Tampa Bay. Since the 1990s, the TBEP’s goal has been “holding the line” on nitrogen discharges, even as the region’s population is anticipated to grow 1.8% in 2018 to over 3.1 million people.

“Tampa Bay is now one of the few urban water bodies in the US where a regulatory designation for nutrient impairment has been removed because of steadfast actions of local stakeholders — collectively through the Tampa Bay Nitrogen Management Consortium,” Sherwood said. “This group has proven to be so effective that the entire Bay is now meeting stringent nutrient criteria adopted by the Florida Department of Environmental Protection and approved by the US Environmental Protection Agency.”

However, as the region continues to grow, replacing natural areas and farms with houses and shopping centers, it’s going to be harder to hold the line. “We’ve already picked the low-hanging fruit in terms of targeted nutrient load reduction projects that government and private industries have implemented. Now it’s going to take a concerted effort by the Tampa Bay community living, working and playing in the watershed to choose a lifestyle that minimizes impacts to the Bay and educate them on the value a clean bay means to the region.”

Nearly 20% of the jobs – and a significant portion of the region’s real estate tax base – rely on a healthy bay, according to a study completed by the Tampa Bay Regional Planning Council in 2014, he notes. “We’ll need people across the region working together to protect the bay. Programs like Be Floridian and Pooches for the Planet were very effective, so we’ll be introducing a new public outreach campaign to help reduce the potential for sanitary sewer overflows later this year.”

And as sea level rise reshapes the extensive coastal shorelines restored over the last 20 years, bay managers will need to look upslope and focus on working with private landowners as well as purchasing available lands. “Preserving and protecting coastal uplands has always been important but they’re more important than ever with sea level rise,” Sherwood said. “Many important coastal habitats, like mangroves and marshes, can move upland, if the rate of rise is slow enough, but not if they’re stopped by seawalls or urban development.”

TBEP also is encouraging its partners to look at innovative solutions to reduce stormwater run-off impacts and damages to estuarine wetlands. For instance, a new bridge project along the Courtney Campbell Causeway aims to improve tidal circulation and water quality to further benefit seagrass in northern Old Tampa Bay.

Building Partnerships to Protect the Bay

A native of Peekskill, New York whose family moved to New Port Richey when he was ten, Sherwood loved the rivers and forests of the northeast and then jumped straight into chasing redfish along Pasco’s Gulf of Mexico coast. Knowing he wanted to spend a career protecting the waters he loved, he earned a bachelors in marine biology from the University of West Florida and then a masters in marine fisheries ecology from the University of Florida.

He started as a marine research associate with the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission and then joined the Environmental Protection Commission of Hillsborough County before joining TBEP in 2008 as the program scientist.

Now, as head of the program, the 41-year-old Sherwood faces yet another challenge: bridging the gap between the early citizens and resource managers who helped turn Tampa Bay from what CBS News called a “dead zone” in the 1970s to one of the world’s cleanest urban estuaries. “Younger people just don’t realize just how far we’ve come,” he said. “We need to foster those relationships to make sure they know about our accomplishments – and the potential to backslide – to make sure that the water quality in the bay is just as good 20 years from now as it is today.”