Tampa Bay is on the frontline of global sea-level rise, but it’s not just our world-renowned beaches at risk.

Three neighborhoods selected to be part of the Tampa Bay Regional Planning Council’s (TBRPC) Resilient Ready Tampa Bay planning project show how differently sea level rise will impact an inland site and a community at the northern tip of the bay, as well as a barrier island.

The Resilient Ready initiative, funded by a $273,000 grant from the Florida Department of Environmental Protection’s Resilient Florida Program (FY 2021-22), brought a diverse group of national and international experts to meet with community leaders and to determine how their neighborhoods can be protected as sea levels rise an estimated 11 inches by 2050.

The concept actually started in 2019 in New Port Richey when TBRPC Senior Planner and Urban Designer Sarah Vitale spent two weeks in New Port Richey helping the city develop a plan to cope with flooding. “The Pithlachoscotee River runs through downtown, which is an asset but also something to plan and prepare for in terms of drainage and future flood risks,” she said. “The question posed was what if we turn this water problem into an opportunity and design a stormwater system that doubles as a floodable park.”

The city spent three years exploring how to make it work, and is now building a $1.6 million park with partial funding from the state. “We could see how this rapid design approach worked, and it inspired us to take it a step forward and organize design charrettes so that other local governments can learn the value of this design-led approach,” Vitale said.

Drawing on national and international expertise, the charrettes were led by Andy Sternad, an architect and urban designer with Waggonner & Ball from New Orleans, which helped rebuild the city to be more resilient after Hurricane Katrina, and Robbert de Koning, a landscape architect from the Netherlands who specializes in managing waters and creating sustainable communities.

“This project was designed to help local governments work through the first few critical steps in problem-solving, really to get the ball rolling,” Vitale said. “It demonstrates what’s possible in these three study areas bringing different disciplines together and exploring innovative ideas from around the world in a productive workshop setting. This helps governments get ready for the next step, which is pursuing funding.”

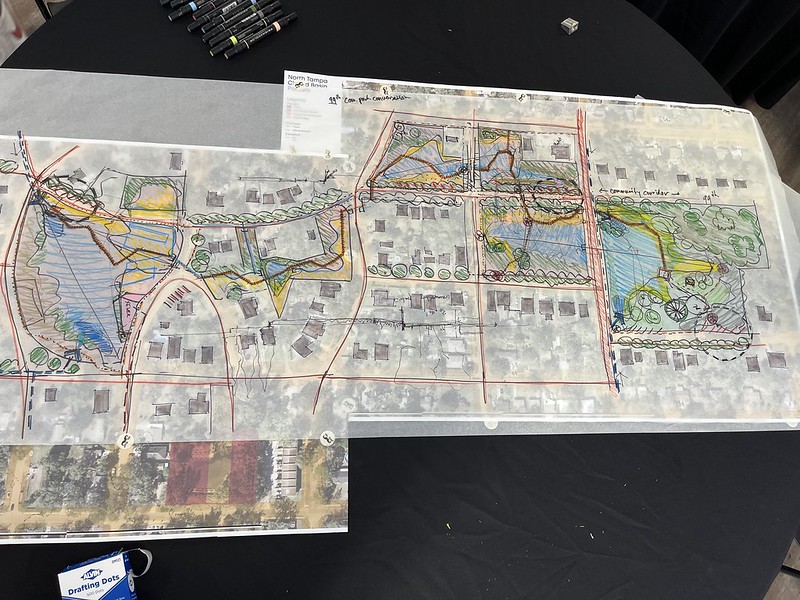

Planners from the three neighborhoods – Pass-a-Grille in St. Pete Beach, R.E. Olds Park in Oldsmar and the North Tampa Closed Basin (a community just north of the Hillsborough River) – were invited to participate in three-day charrettes to develop plans, create drawings to illustrate how they would work, and then estimate costs for the strategies. The first day was on-site so the experts could see the problem first-hand, then two days were spent developing strategies and creating conceptual designs.

In the North Tampa Closed Basin, which contains a series of sinkholes in an underserved community, planners envisioned a park system with a series of detention ponds redesigned to include shallow shelves on their edges to attract wildlife. “We started at Elmer Pond, a fenced detention pond that works for water but it doesn’t work for the community and doesn’t work for the ecology,” said de Koning.

In the North Tampa Closed Basin, which contains a series of sinkholes in an underserved community, planners envisioned a park system with a series of detention ponds redesigned to include shallow shelves on their edges to attract wildlife. “We started at Elmer Pond, a fenced detention pond that works for water but it doesn’t work for the community and doesn’t work for the ecology,” said de Koning.

The city already has done a great deal of work, including voluntary buy-outs of homes in the floodplain but the new vision for the neighborhood includes networked detention ponds that overflow into each other to filter water, shallow shelves along the water’s edge to attract wildlife, larger parks with shade trees, sidewalks and boardwalks and a new corridor to connect neighborhoods with the parks, along with enhanced ecological benefit.

In Oldsmar, where the city’s iconic R.E. Olds Park dominates the shoreline, planners had 15 acres of publicly held land to work with but were challenged by a large watershed draining into the area, poor water quality in Old Tampa Bay, and the fact that the community is a storm surge funnel at the top of Tampa Bay.

Planners took an adaptive approach to coping with stormwater as well as storm surges with a design that keeps water out of some locations while allowing it to flow into others. “We’re biased towards the adaptive scenario – we need to mitigate for drainage and buffer for storm surge events,” said de Koning.

Small berms are planned as a valuable first step, although they aren’t a long-term solution. Redevelopment already is occurring, which gives the city the opportunity to incentivize building the newer homes higher. Additionally, wide rights of way on roads and corridors in the downtown area can be used to collect and filter stormwater. Offshore, new mangroves and oyster reefs are planned, with hopes of recruiting seagrasses, to slow down storm surges and improve water quality.

Small berms are planned as a valuable first step, although they aren’t a long-term solution. Redevelopment already is occurring, which gives the city the opportunity to incentivize building the newer homes higher. Additionally, wide rights of way on roads and corridors in the downtown area can be used to collect and filter stormwater. Offshore, new mangroves and oyster reefs are planned, with hopes of recruiting seagrasses, to slow down storm surges and improve water quality.

“Some residents may have water in their yards, so their house doesn’t flood,” notes Ashlee Painter, the city’s sustainability coordinator.

In St. Pete Beach, the most challenging of the three sites, planners were charged with “dreaming the best possible scenario” for the narrow, low-lying barrier island. It begins with a defend-and-adapt scenario that calls for raising the seawall and continuing beach renourishment to buy time to prepare other adaptive measures.

“It’s very narrow, it’s very low and it’s very risky – it’s also very beautiful,” said de Koning. “We can raise the seawall and continue beach nourishment to buy time while we prepare for other adaptive measures,” adds Sternad.

Planners face regulatory, environmental and political push-back as they move beyond those initial stages, Sternad said. Building offshore structures to slow wave action may impact seagrasses which are protected habitat, and residents may balk at mangroves blocking their views. Alleys leading to homes may need to be transformed for flood protection, and some homes will need to be raised. “The vast majority of our residents may not even be aware of what’s happening, or may not believe it,” said Mike Clark, the city’s public works director.

Learn more: The final report on the Resilient Ready Tampa Bay Project is now online.