Photo by Mark Rachel

While many birds have outrageous

courting rituals with elaborate dances, the reddish egret dances for its dinner. With extraordinarily long legs and a 4-foot wingspan, the reddish egret stalks its prey in an unforgettable foraging routine. It locates prey —mostly small fish—by sight and dashes after them, zig-zagging as it runs through the coastal shallows. Typically, reddish egrets carry their wings outstretched, a tactic believed to reduce glare so they can see underwater more effectively.They spear fish with their distinctive pink-and-black bill in a lightning-fast move with their S-shaped neck.

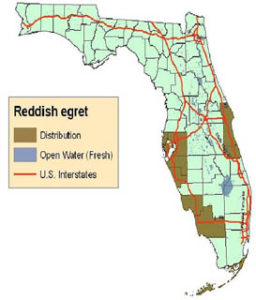

Hunted nearly to extinction in Florida in the 1880s because their fluffy reddish plumes were prized as decorations for ladies’ hats, reddish egrets now appear to be making a slow but sure comeback in Florida. There are as many as 318 nesting pairs in Florida, according to a recent survey by the Florida Audubon Society with funding and assistance from the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission and the Avian Research and Conservation Institute.

The largest number, 95 pairs, was found in the lower Florida Keys, with Tampa Bay and Southwest Florida coming in next at 85 to 92 pairs, including colonies in both Hillsborough and Pinellas counties.

Reddish egrets are still listed as a Threatened species in Florida and considered the rarest heron in North America.

Counting reddish egrets isn’t easy. They typically nest among colonies of other birds, high in the mangroves and often carefully concealed by leafy branches. “We decided early on that a direct count was the best choice, but that we couldn’t get close enough to flush the birds,” notes Ann Paul, Audubon’s regional coordinator for Tampa Bay.

The team surveyed 306 sites, some by boat and some by quietly maneuvering through tall mangroves (particularly in the Keys). “We only found reddish egrets at 59 sites, but we wanted to take the time to see if they were nesting with other colonies where they hadn’t been identified in the past,” she said.

Island sites like the Alafia Bank in Tampa Bay have inland areas where birds may be nesting, but researchers could never get close enough to actually see the birds, she adds.

Island sites like the Alafia Bank in Tampa Bay have inland areas where birds may be nesting, but researchers could never get close enough to actually see the birds, she adds.

The surveys take advantage of the birds’ documented habits. “Like many birds, reddish egrets are very protective of their young, so we know that one parent is always on the nest if there are eggs or nestlings,” Paul said. “If we’re there right after dawn, we may see one leave for food and then return again mid-morning so its mate can eat too.”

Unlike many birds, reddish egrets feed their young with prey captured in saltwater so they live entirely in coastal habitats. That made them an easy target for plume hunters in the 19th century.

“Most of Florida was pretty inaccessible by land, but anyone with a sailboat could reach almost anywhere on the coast,” she said. “Since bird plumes were literally more expensive than gold – about $32 per pound in 1880 dollars – they were overharvested, and their plumes shipped to fashionable women in New York, Boston and Paris.”

No reddish egrets were seen in Florida between the 1880s and 1938, when a single nesting pair was identified in Florida Bay. The first reddish egret in Tampa Bay was documented in the mid-1970s, and the colony at the Richard T. Paul Alafia Bank Bird Sanctuary is now listed as among the state’s most successful.

Even with the significant increase in population over the past 70 years, however, Paul doesn’t count reddish egrets as a success story. “This is more of a precautionary tale,” she said. “We’ll never get back the populations we had before the plume trade – but we need to protect their nesting and foraging sites now and carefully monitor their populations in the future.

Learn more:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wBiEUbfhQBo, for a video of the reddish egret’s distintive dance

http://myfwc.com/wildlifehabitats/imperiled/profiles/birds/reddish-egret/ for information about reddish egrets in Florida

http://www.heronconservation.org/herons-of-the-world/reddish-egret/ for more information about their breeding and foraging habits

http://reddishegret.org/wp/about/, the Reddish Egret Working Group, composed of researchers from Florida, Alabama, Texas and Louisiana as well as Mexico, the Bahamas and Baja California.

[su_divider]