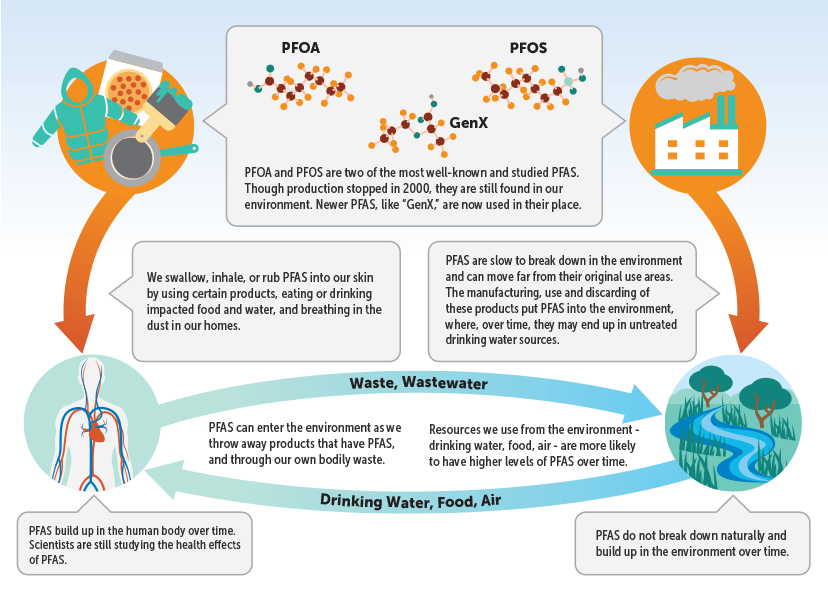

Like DDT when it was first introduced in the 1930s, PFAS were originally considered miracle products. They made fire-fighting foam more effective, prevented food from sticking to cookware, enabled water- and stain-resistant fabrics and carpets, and extended the wear time of lipstick and mascara. But like DDT, researchers are uncovering the dangers of PFAS long after they were unleashed in the world.

PFAS, formally known as per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, have extraordinarily strong bonds so they’re dubbed “forever chemicals.” They’re found nearly everywhere – from drinking water, dust and dairy products to fire-fighting foam, fish and food packaging. Researchers have linked them to a wide variety of illnesses, including decreased fertility in women, developmental delays in children, and an increased risk of some cancers such as prostate, kidney, and testicular cancer.

And they’re toxic in such tiny concentrations that the Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) standards for drinking water limit two types of PFAS to four parts per trillion (ppt), or about one drop of water in 20 Olympic-sized swimming pools.

While ongoing tests by Tampa Bay Water, the region’s primary water utility, show that PFAS levels meet standards in most locations, the utility was awarded $21 million in a class-action lawsuit against PFAS manufacturers to treat water as needed.

Although drinking water for much of the region appears to meet those standards, water, sediments, and fish in Tampa Bay often don’t. Three researchers – John Bowden at the University of Florida (UF) and Steve Murawski and Sherryl Gilbert at the University of South Florida USF) – are documenting levels of PFAS that far exceed the EPA recommendations in Tampa Bay’s water, fish and sediments.

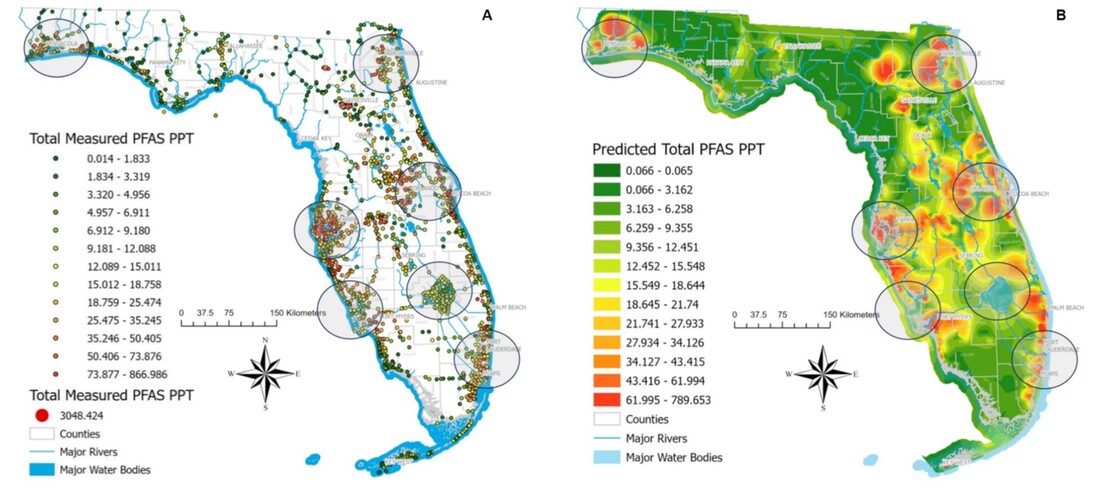

Bowden, who sampled more than 2,300 sites in surface waters across the state with a team of citizen scientists, notes that PFAS levels are significantly higher in Tampa Bay than in other areas. Pinellas and then Hillsborough rank highest on the list of counties for hits above the maximum contaminant levels for PFAS found in Florida counties. “There’s no clear source for them,” he adds. “Military bases, where fire-fighting foam is used, are one source, but it doesn’t explain high levels at other sites.”

Wastewater spills, like those that often occur after heavy rain events, may also be implicated. Bowden compared data from the Florida Department of Environmental Protection documenting 7,395 wastewater spills with the statewide PFAS heatmap, which showed a striking similarity. “More research is needed to investigate this potential source of PFAS pollution,” he said.

Even treated wastewater can be a source of PFAS because most facilities only remove about 10% of PFAS, Bowden adds. “Most of the contaminants in the processed material are dumped back into our waterways,” Bowden said. “If our drinking water comes from these sources, it will often contain PFAS. What should be alarming for all Floridians is that in the springs, which are often destined for use as drinking water, PFASs are present.”

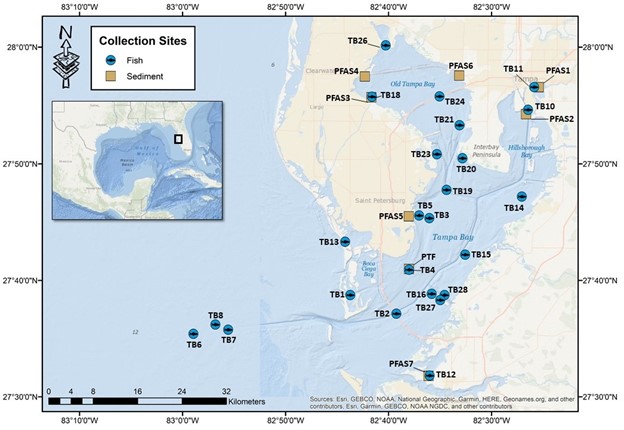

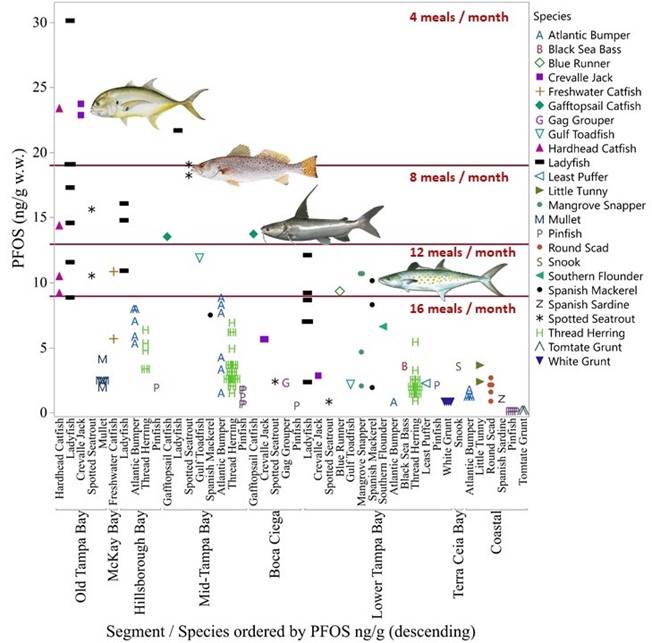

Closer to home, Murawski and his team from USF had begun looking at PFAS in Tampa Bay in 2020 and documented concentrations of more than 1,000 ppt in sediments in Old Tampa Bay and Hillsborough Bay, with lower concentrations noted in other bay segments. Perhaps more concerning is the extreme levels of PFAS in some fish caught in the bay. Catfish, ladyfish, and crevalle jack caught in Old Tampa Bay had concentrations of more than 20,000 ppt. According to guidelines drafted by the State of Michigan, fishermen should limit consumption of two of the most fish popular fish caught in Tampa Bay — snook and spotted seatrout.

The Tampa Bay Surveillance Project is a five-year study that began in 2023 with $3.4 million in funding from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and the South Carolina Sea Grant Consortium. Murawski’s team is taking a closer look at multiple contaminants in the bay and the living resources they impact. Along with PFAS, they are documenting levels of pharmaceuticals, herbicides and pesticides, and their potential impact on fish, oysters, and barnacles.

Their first efforts focus on the fish most likely to be eaten – including red drum, spotted seatrout, snook, and sheepshead — with a target of harvesting 10 of each fish in each of the bay’s six segments four times a year. Separate studies looking at contaminant levels in oysters and barnacles also are planned.

A companion study, underway in partnership with Eckerd College, is looking at the effects of combined contaminants – including PFAS, pharmaceuticals, PCBs, PAHs and pesticides and other chemicals among subsistence fishermen.

The concept for the Tampa Bay Surveillance (TBS) project began more than 15 years ago with the Deepwater Horizon disaster. Scientists from USF were on the scene soon after the disaster and the team collected water samples and other critical information near the blowout site. Murawski went on to lead an international consortium that studied the environmental impacts of the oil spill, comprising 18 institutions and culminating in more than 250 scientific publications.

“Through our work on the spill, we learned a lot about the impacts of these contaminants and acquired highly specialized equipment to do the science,” Murawski said. “TBS is a natural extension of our work on Deepwater Horizon.”

This is the second part in a three-part series on PFAS. The first, Diamonds have nothing on PFAS, focused on how PFASs became so widespread, and why they are dangerous. The third, Avoiding PFAS: Easier said than done, will be published on January 30.

By Vicki Parsons, originally published January 22, 2026