Across the state, beaches close when high levels of fecal bacteria are found. Beyond the general “ick” factor, poop poses risks to human health in terms of disease-causing pathogens, including salmonella and noroviruses, plus it carries high levels of nutrients that can cause environmental damage.

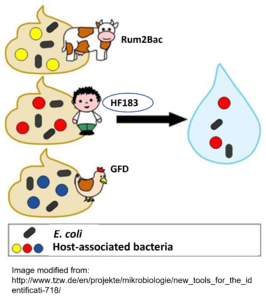

But not all poop is created equal, and it’s not easy to differentiate between human feces and those from dogs, cattle, wild animals and birds. However, distinguishing between the origins of fecal contamination sources is critical because sources vary in their potential risk of causing illness.

Most pathogens are host-specific. Human feces carry dangerous viruses such as norovirus (the “cruise ship virus”), while feces from birds or dogs are less likely to cause health problems. That means that beaches sometimes close, and beachgoers question water quality, even when there is no reason for serious concern.

The “Poop Sleuthers” in Valerie Harwood’s lab at the University of South Florida’s (USF) Department of Integrative Biology are out to change that. New technology uses quantitative PCR (qPCR or polymerase chain reaction) to connect fecal matter to specific sources, tracking microbial pollution and, indirectly, nutrient pollution. “Host-associated bacteria have unique DNA sequences, so we can use the qPCR to identify the source,” said Amanda Brandt, the postdoctoral fellow leading the USF research.

“Determining the source is really critical for risk assessment because human pathogens pose the greatest risk,” she said. “I’m not saying that feces from other animals don’t pose risks but human pathogens are typically much more infectious to humans than bird pathogens. Human feces generally pose a greater risk to human health because there are a wider variety of pathogens present or present in greater concentrations.”

For humans to acquire an infection from animal feces, the fecal organism (whether bacterial, viral, or protozoan) has to be infectious to humans – called a zoonotic pathogen. These are relatively rare, with obvious exceptions like COVID.

Along with assessing the risk of fecal contamination, tracking it back to a source may allow the contamination to be halted. “I’ve worked on projects where we go out and find someone who has an illicit connection directly to the waterbody. We work with the appropriate authorities who can force the people to remove that connection, and water quality is restored.”

On the other hand, if tracking the source shows that the fecal contamination comes from birds—commonly seen in some areas—little can or should be done about it.

Another challenge for researchers tracking bacteria associated with human sewage is that microbial DNA survives wastewater treatment so it can be difficult to differentiate between sewage and reclaimed water, particularly in urban settings. That requires a second test in which the qPCR is performed on cultured E. coli—the bacteria will grow if the sample came from untreated water, but cannot live in reclaimed water that has been thoroughly sanitized.

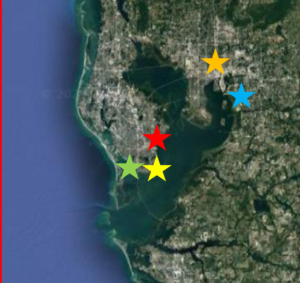

With funding from the Environmental Protection Agency’s Gulf of Mexico Division, the USF research team identified five sites in Tampa Bay that consistently exceeded fecal indicator standards while having different surrounding land uses and potential sources of E. coli.

- Hamilton Creek borders ZooTampa, where researchers expected to find fecal matter from zoo animals but discovered it was primarily impacted by birds and recycled water.

- Bullfrog Creek, near the coast of Tampa Bay in central Hillsborough County, is primarily an agricultural area. The primary sources of fecal matter were human sewage and wildlife.

- At North Shore Park in St. Petersburg, birds and reclaimed water were the primary sources of bacteria, while a signal for dog feces was occasionally seen.

- Frenchman Creek in St. Petersburg is adjacent to Eckerd College, Maximo Park and a marina. The USF team found human sewage, probably trackable from the marina, and traces of bird fecal material.

Additionally, segments of Salt Creek, Booker Creek and Bayboro Harbor, with homes, businesses, parks and marinas in the surrounding areas, were sampled. They showed the highest level of human sewage of any of the other test sites, as well as bird feces and trace amounts of dog feces.

“Perhaps most surprising were the results of the culturable E. coli H8 tests in these areas, since E. coli does not survive well in estuarine and marine environments,” Brandt said. “Even so, we observed high concentrations of culturable E. coli, and many times these living E. coli tested positive for the sewage-associated H8 gene, indicating that human sewage is regularly added to these water bodies.”

The latest technology, called microfluidic qPCR is “qPCR on a chip” that simultaneously performs more than 60 assays in about two hours, providing nearly immediate results to determine the risks accurately. As the technology becomes more available and more acceptable, Brandt hopes that alternate benchmarks can be set that accurately reflect the risk posed by fecal contamination, along with the ability to intervene and mitigate many of the issues when they are clearly identified.

Originally published June 3, 2024