Floridians should plan for harmful algal blooms in much the same way they prepare for hurricanes, says Jennifer Shafer, co-executive director of the Science and Environmental Council of Southwest Florida. We can hope they won’t occur but having a plan in place will help minimize the impact of the toxic algea.

Floridians should plan for harmful algal blooms in much the same way they prepare for hurricanes, says Jennifer Shafer, co-executive director of the Science and Environmental Council of Southwest Florida. We can hope they won’t occur but having a plan in place will help minimize the impact of the toxic algea.

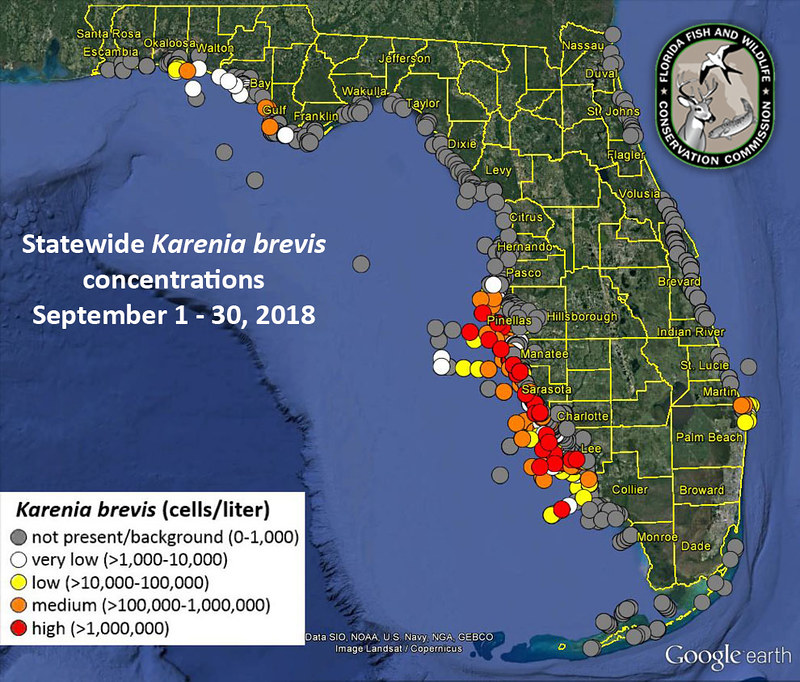

Red tide — officially known as Karenia brevis — is a naturally occurring dinoflagellate that originates in the Gulf of Mexico and can be transported to coastal waters where it feeds on nutrients from stormwater and wastewater. When it occurs at high levels, it produces neurotoxins that kill fish, birds and other wildlife as well as causing respiratory distress for humans and other land-based animals.

And like hurricanes, the latest reports on red tide aren’t showing any discovery that’s likely to actually change anything about the blooms that were first documented when native Americans described toxic “red water” to Spanish explorers in the 1500s. In fact, warmer waters caused by climate change and increased nutrient runoff from the state’s growing population may make the blooms last even longer.

To address the multiple impacts of red tide, a new report by Shafer for the council looks at the 16-month red tide event that began in November 2017 for lessons learned and best practices from counties bordering Tampa and Sarasota Bay. It makes a series of recommendations, including a call for increased regional cooperation, as well as providing draft emergency response plans for each of the five counties, including Sarasota, Manatee, Hillsborough, Pinellas and Pasco.

The single most important innovation came from Pinellas and Hillsborough counties who chose to focus on dead fish floating offshore rather than waiting for them to sink to the bottom or wash up on beaches. Pinellas, near the northern tip of the bloom, collected more than 1,800 tons of dead fish, compared to 255 and 316 tons collected in Sarasota and Manatee counties, respectively. Hillsborough, monitoring the mouth of the bay with aerial surveillance, captains’ reports and increased sampling, helped keep dead fish out of other sections of Tampa Bay by capturing them before they could enter.

The single most important innovation came from Pinellas and Hillsborough counties who chose to focus on dead fish floating offshore rather than waiting for them to sink to the bottom or wash up on beaches. Pinellas, near the northern tip of the bloom, collected more than 1,800 tons of dead fish, compared to 255 and 316 tons collected in Sarasota and Manatee counties, respectively. Hillsborough, monitoring the mouth of the bay with aerial surveillance, captains’ reports and increased sampling, helped keep dead fish out of other sections of Tampa Bay by capturing them before they could enter.

“Besides the obvious impact on beaches, nutrients from dead fish may lead to a longer red tide event and more severe seagrass die-offs,” Shaffer said.

Collecting dead fish offshore, however, was more easily said than done. Without a formal plan in place before they started washing up, Pinellas had to work through the details of hiring contractors and subcontractors to collect the fish and then find ways to stage dumpsters for the putrid biohazardous waste so they were available at the right time and place.

“The equipment was simply insufficient,” Shafer said. In the future, counties need greater access to flat-bottom skiffs, outrigger vessels, trash skimmers, beach rakes, wave runners, blowers, turbidity barriers, and soft-sided dumpster bags as well as personal protection equipment for people working near the dead fish.

Additionally, counties need to ensure that their prime debris contractors (usually hired to clean up after hurricanes) can hire subcontractors like fishermen, shrimpers, fishing guides, drone operators and drivers who can move dumpsters efficiently. Contracts with those debris removal specialists also may need to be modified to cover the biohazardous dead fish along with more typical hurricane debris. With appropriate paperwork in place, those water-based businessmen are likely to be searching for an income to replace what had been lost to red tide.

Regional coordination would benefit all counties

Another top priority identified by the council’s research is increased coordination among local governments who met informally but could have benefited from more strategic planning as a region, Shafer said. The ability to share data was limited by condition assessments and data streams in different formats. Counties also competed for the limited number of subcontractors available for the cleanup instead of sharing those resources.

Another top priority identified by the council’s research is increased coordination among local governments who met informally but could have benefited from more strategic planning as a region, Shafer said. The ability to share data was limited by condition assessments and data streams in different formats. Counties also competed for the limited number of subcontractors available for the cleanup instead of sharing those resources.

Heads of both the Tampa Bay Estuary Program (TBEP) and the Agency on Bay Management (ABM) support a more regional approach to dealing with the impacts of red tide. “This is a great opportunity for regional cooperation and to create standard operating procedures for accessing and reporting data,” said Barbara Sheen Todd, co-chairman of the ABM. “We can reach out to policymakers to bring them on board.”

TBRPC will schedule a meeting of county coordinators and other stakeholders to begin discussions on advancing regional cooperation and how it can can support local government as they prepare for another red tide event.

TBEP also plans to present the report to its policy board, which is composed primarily of elected officials from cities and counties in the Tampa Bay watershed, said Ed Sherwood, TBEP executive director. Additionally, TBEP’s expertise in open science can be used to create a regional database that could share information on red tide in real time on a common platform.

“Floating debris doesn’t stop at the county line,” Shafer said. “Regional cooperation would have made early intervention on debris clean up much more efficient, and more capacity would have made a healthier bay and a happier public.”