Piney Point, the abandoned phosphate plant that has dumped more than a billion gallons of contaminated water into Tampa Bay over a 60-year period, may finally be turning the corner. “This is the final chapter,” said John Coates, program manager for the Florida Department of Environmental Protection’s Mining and Mitigation Program. “This is the closure of this facility, once and for all.”

By Vicki Parsons, originally published September 16, 2022

Piney Point has been problematic almost since it was built in 1966. Spills began in the 1970s, highlighted by a 10-million-gallon release in October 2001 that carried 16.2 tons of nitrogen, among other contaminants, into lower Tampa Bay, which was more than three times the annual nutrient budget for that bay sector.

After the 2001 release, more than 200 million gallons of water was removed from the site to prevent future releases. HRK Holdings purchased the property to develop as an industrial park, but then allowed Port Manatee to use the empty gypsum stacks to store dredged material. The liner apparently wasn’t designed to hold that much sediment and ripped. Just months after dredging began in April 2011, another 169 million gallons of water was released in an emergency discharge to relieve pressure on the dikes.

After steady increases over the last decade, water levels increased to the point where another leak in the containment system required managers to release 215 million gallons of wastewater in 2021 to prevent an entire pond from collapsing. Most researchers believe that the release contributed to Tampa Bay’s worst red tide in 50 years, which resulted in massive fish kills as far north as Hillsborough and Old Tampa bays.

This isn’t the first time that the state has tried to close Piney Point, though. “This sounds exactly like the plan from nearly 20 years ago,” said Suzanne Cooper, environmental planner for the Tampa Bay Regional Planning Council at the time.

Moving Forward

Assuming all goes as planned, the gypsum stacks that tower over Bishop Harbor will become a stormwater system by the end of 2024. The first step is draining nearly 500 million gallons of water from four ponds so liners can be installed, then covered with two feet of soil and vegetation to protect them from UV rays and temperature extremes. Properly installed and maintained, the liners should last more than 50 years.

For now, there is enough storage on the site to accommodate at least 27 inches of rain before water would need to be released to protect the decades-old dikes, said Herb Donica, the court-appointed receiver directing the site’s closure.

Parts of the site, including properties adjacent to U.S. 41, are expected to be sold and developed. The future of the stacks themselves is less clear. HRK still owns the gypsum stacks but they will be expensive to manage, Donica said. He made it clear that the stacks will not be developed and is hopeful that they can be repurposed as a wildlife refuge in the future. Some beach-nesting birds already are utilizing parts of the site, notes Mark Rachel, Audubon Florida’s coastal island sanctuaries manager.

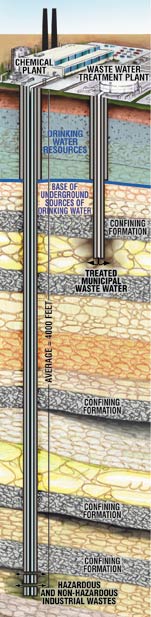

About 594 million gallons of the water will be treated and injected into a 3,000-foot-deep well under the Floridan Aquifer that supplies much of the state with drinking water. An onsite water treatment plant will remove suspended solids and reduce nutrients to maintain the performance of the well. Radiological testing consistently shows that it is below drinking water standards.

The treatment plant and well should be up and running by mid-2023, Donica said. Manatee County Utilities is trucking about 100,000 gallons per day — 34 million gallons so far — to its nearby wastewater treatment plant, and then selling it as reclaimed water. A spray mist system also continues to operate, speeding evaporation from the ponds.

Construction is underway now on the first pond to close the first pond, OGS-S, one of the oldest and smallest ponds. About 4.5 million gallons of water was released, but it was stormwater, not water used to process the phosphate, Donica said. “We tested it continuously. The total nitrogen ranged from about 2.3 to 3.5 parts per million – about one-tenth of one percent of what the guidelines call for.” (The guidelines are the federally adopted maximum daily loads for Lower Tampa Bay.)

The legislature already has budgeted $100 million from federal COVID relief funds for the clean-up but more funding is likely to be necessary based on rising construction costs. FDEP has sued the current landowner, HRK Holdings, although the company filed for bankruptcy following the 2011 spill. “We have every intention of holding HRK accountable,” said Mark Rains, chief science officer for the state. “This is just not being hung around the taxpayers’ necks. We do have plans in place and in action to hold HRK accountable to the greatest extent possible.”

Piney Point: Problematic for More Than 50 Years