By Mary Kelley Hoppe

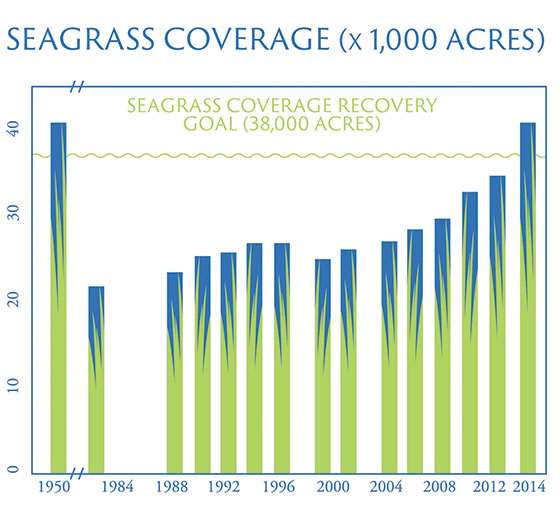

Above: Dramatic improvements in water quality have allowed seagrasses to rebound to levels not seen since the 1950s. Tampa Bay now harbors more than 40,295 acres of seagrasses, exceeding a goal of 38,000 acres baywide set in 1995 by the Tampa Bay Estuary Program. Photo by Jimmy White, jimmyWhitePhoto.com.

The discussions weren’t contentious, but they were challenging. Was it possible to bring back an estuary on the brink of collapse in the 1970s and restore it to 1950s standards?

Most of the leaders meeting in the mid-1990s thought it might be possible but perhaps not probable — and certainly not in less than 20 years. Even so officials and environmentalists set a truly ambitious goal: improve water quality to levels that would allow seagrass regrowth to amounts present in the 1950s even as the region’s population grew by millions of people.

That gutsy goal was achieved earlier this year with a report showing the seagrasses in Tampa Bay — a key barometer of the bay’s health because they need clean water to flourish — were as widespread as they had been more than 60 years ago.

The latest survey results released in May by the Southwest Florida Water Management District show just how far the bay has come. Tampa Bay now harbors more than 40,295 acres of seagrasses, exceeding a goal of 38,000 acres baywide set twenty years ago by the Tampa Bay Estuary Program.

Altogether, scientists documented more than 5,000 acres of new seagrasses from 2012 to 2014. Seagrass gains were reported in every bay segment, including a 47% increase (3,273 acres) in Old Tampa Bay, an area historically lagging behind in seagrass recovery and water quality. Old Tampa Bay encompasses the waters from the Gandy Bridge north to Oldsmar and east to Tampa.

In Hillsborough Bay, more than 525 acres, a 36% increase over 2012 results, was observed. Traditionally the most impacted part of the bay, Hillsborough Bay surrounds downtown Tampa, including the iconic Bayshore Boulevard and its busy industrial port.

The bay’s remarkable turnaround is rooted in the extraordinary groundwork of regional cooperation laid decades ago, according to Dick Eckenrod, former director of the TBEP, which was established in 1991 to develop a comprehensive plan to sustain the bay’s recovery. “Much of the heavy lifting had begun by the time we set the goal for seagrass recovery in 1995,” Eckenrod said.

The Wilson-Grizzle Bill of 1972, calling for advanced wastewater treatment standards, was the first step in the amazing reversal. The following year, the City of Tampa announced plans for the Howard F. Curren Advanced Wastewater Treatment Plant, which sharply reduced nitrogen discharges to the bay when it opened in 1979.

Across the bay, the City of St. Petersburg pioneered the nation’s first large-scale water reuse program, diverting treated wastewater from the bay for use in irrigating lawns and golf courses.

By 1983, water quality was improving. In response to improved water clarity, seagrasses had started to rebound from a low point of 21,600 acres in 1982.

As part of the Comprehensive Conservation & Management Plan for Tampa Bay adopted in 1996, local governments and other stakeholders pledged to hold the line on future nitrogen loadings to the bay to sustain water clarity levels sufficient for seagrasses to flourish. “Our partners, particularly local governments, were interested in setting economically achievable goals, and we were fortunate in having a solid database to develop seagrass recovery and nitrogen loading targets,” Eckenrod added. Since the 1990s, an alliance of local governments and key industries known as the Tampa Bay Nitrogen Management Consortium has collectively invested more than $500 million in projects to offset nitrogen discharges.

“I’m not aware of any other urban estuary in the country, or even the world, that has achieved this kind of recovery,” Eckenrod said. “This is a remarkable achievement, made even more so when you consider that the bay region has grown by more than 1 million people in the last 15 years,” said Holly Greening, who succeeded Eckenrod as TBEP director in 2007. “This kind of environmental recovery is a living testament to the collective efforts of all of us working together – the cities and counties, the private sector and citizens who treasure the bay.”

Greening cautions against becoming complacent about success and slacking off on bay restoration and protection efforts. With growth accelerating and the effects of historic rainfall this summer that clouded bay waters with stormwater runoff, “it will be a challenge to sustain the momentum and these types of gains in the coming years.”

“But,” she added, “we should definitely pause for a moment, as a community, to celebrate and savor what is truly a major milestone in the decades-long effort to restore our bay.”

Community leaders involved in the bay’s recovery will gather from 10 am to noon on October 16 at Tampa’s Picnic Island Park to celebrate the historic seagrass gains and participate in a ceremonial seagrass planting.

“I think one of the mistakes we’ve made is that we don’t talk enough about the economics of Tampa Bay,” said former state representative Mary Figg, co-author of the 1987 Grizzle-Figg Bill that strengthened wastewater treatment standards in Southwest Florida. “We have to remember that there are two costs for regulation – a cost for action and a cost for not taking action.” A recent economic study has shown that one in five jobs in the communities surrounding the bay are dependent on its good health, and Tampa Bay contributes more than $20 billion to the region’s economy.

Early collaboration sets stage for recovery

While the transition to advanced wastewater treatment was a critical first step in the bay’s recovery, advocates pressed for greater study of the bay and a management structure to coordinate restoration and protection.

That led to the first Bay Area Scientific Information Symposium (BASIS) in 1982, which called for the creation of a study commission to identify major bay issues. Two years later, the Florida Legislature created the Tampa Bay Management Study Commission to develop a workplan. Released in 1985, The Future of Tampa Bay was the first bay management plan, developed with input from a diverse group of stakeholders who reaffirmed the need for a standing entity to advocate on behalf of the bay.

The Agency on Bay Management (ABM) was established later that year as a committee of the Tampa Bay Regional Planning Council. The 40-member committee included scientists, local governments, and representatives of industry, environmental and recreational interests.

“It was critical to have everyone under one roof – regulators, phosphate companies, utilities, the environmental community and other entities, speaking openly and searching for solutions to problems,” said former Hillsborough County Commissioner Jan Platt, ABM’s first chairperson.

Before long, ABM was chalking up a succession of victories, building clout and credibility across the region and in Tallahassee. In 1987, the Florida Legislature created the Surface Water Improvement and Management (SWIM) Act, authorizing the state’s water management districts to implement plans to improve Tampa Bay and other priority water bodies.

In 1990, Congress designated Tampa Bay an “estuary of national significance,” leading to the creation of the Tampa Bay National Estuary Program and development of long-range plans for bay restoration that eventually led to the seagrass recovery goal.

In 1998, these partners signed a formal Interlocal Agreement pledging to achieve the goals of the newly completed Comprehensive Conservation and Management Plan (CCMP) for Tampa Bay, called Charting The Course, culminating six years of scientific research into the bay’s most pressing problems.

“These were huge victories for all of us,” said Platt.

The TBEP continues to coordinate the overall protection and restoration of the bay with assistance and support from its many partners, updating the CCMP every 10 years to summarize and evaluate information and incorporate new or emerging action areas. And as this major milestone is accomplished, the third version of the CCMP — due out in late 2016 — is currently being drafted.

“The goals, as always, will be determined by the partners as we move through the process,” Greening said.