When most people think of history in Tampa Bay, they envision Ponce de Leon searching for the fountain of youth, pirates burying treasures, and enormous cigar factories surrounded by neighborhoods of shotgun homes.

A new exhibit opening at the Tampa Bay History Center brings an innovative vision to that history – literally a bird’s eye view of wildlife and conservation in the region and around the world. Created in collaboration with the Audubon Florida’s Coastal Islands Sanctuaries, the exhibit highlights the ways birds have influenced human culture – within and beyond the Tampa Bay region.

Even prehistoric humans, ancient civilizations and western cultures were fascinated by birds and incorporated them into their lives. The exhibit provides glimpses of this and moves through artists to 19th-century John James Audubon’s work which captivated Europeans and Americans alike with the beauty of birds.

Even prehistoric humans, ancient civilizations and western cultures were fascinated by birds and incorporated them into their lives. The exhibit provides glimpses of this and moves through artists to 19th-century John James Audubon’s work which captivated Europeans and Americans alike with the beauty of birds.

“A lot of what changed the world actually happened right here,” said Ann Paul, Audubon’s regional coordinator for Tampa Bay. “W.E.D. Scott, the first curator of Princeton University’s ornithology department, visited Tampa Bay in 1880 to collect birds for the school’s collection and was astounded by the high large populations of wading birds. He came back in 1886 and found no birds – they’d all been killed for their plumes.”

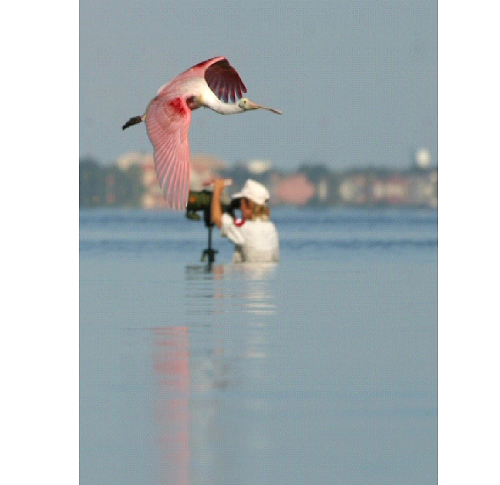

The region’s barrier islands – traditionally home to colonial nesting birds like the iconic roseate spoonbill, herons and egrets – were easily reachable by small craft. “The birds gathered to court and nest when their plumage was at its finest so it was easy to shoot them and then leave the eggs or chicks to die,” she said. “In those days, the feathers were more expensive than gold at $32 an ounce.”

The destruction caused as birds were killed for their beautiful fashionable plumes and eggs were collected and traded as a hobby raised a national alarm. Florida, and Tampa Bay in particular, were bellwethers of this impact and key to the rise of the conservation movement.

When Scott returned home to Princeton, he shared his discovery and that led to the creation of the Audubon Society in Massachusetts and then Florida and other states, which eventually led to the federal bans on selling bird plumes, indiscriminate shooting of native birds and egg collection.

When Scott returned home to Princeton, he shared his discovery and that led to the creation of the Audubon Society in Massachusetts and then Florida and other states, which eventually led to the federal bans on selling bird plumes, indiscriminate shooting of native birds and egg collection.

Tampa Bay also is home to one of the nation’s first national refuges – Passage Key designated by President Theodore Roosevelt in 1905 for nesting and migrating birds. Although it has eroded significantly, it still provides nesting habitat for terns, gulls, skimmers, and oystercatchers and critical wintering habitat for piping plovers and other shore and seabirds. Other federal refuges include the Pinellas NWR near Fort De Soto and Egmont Key NWR and State Park.”

Tampa Bay also is home to one of the nation’s first national refuges – Passage Key designated by President Theodore Roosevelt in 1905 for nesting and migrating birds. Although it has eroded significantly, it still provides nesting habitat for terns, gulls, skimmers, and oystercatchers and critical wintering habitat for piping plovers and other shore and seabirds. Other federal refuges include the Pinellas NWR near Fort De Soto and Egmont Key NWR and State Park.”

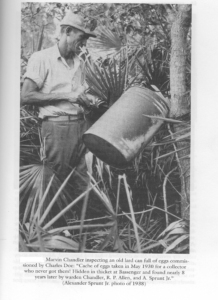

While the exhibit looks at the destruction of the past, it also focuses on the successes that have been achieved since then. One of Audubon’s first live-in wardens was housed at Green Key just north of the Alafia River that was once described as “an enchanted isle… where trees bloom birds.”

When Fred and Ida Schultz arrived in 1934, only about 700 birds populated the island. After just six years of protection, more than 30,000 birds were nesting on Green Key, Schultz wrote in a report to Audubon.

Today, Hillsborough Bay is recognized as a “globally important area” for bird nesting, along with Lower Tampa Bay, including parts of Fort De Soto Park and Egmont Key. Two other areas – Cockroach Bay/Tierra Ceia and Clearwater Harbor/St. Joseph’s Sound – also are recognized as important.

“The Audubon exhibit is a totally new topic for the Tampa Bay History Center but an exhibit on conservation, natural history and wildlife is definitely part of our mission,” notes Rodney Kite-Powell, Touchton Map Library director and Saunders Foundation curator of history. “It was a natural – excuse the pun – fit for us.”

Kite-Powell has been working with the sanctuary staff and volunteers for nearly four years to create the exhibit, he said. “It’s exciting to see what happened – and what’s going on – because I can look out my window and see the results.”

The exhibit includes a timeline of successful conservation initiatives in the Tampa Bay area and the various organizations and agencies responsible for the successes.

But while those efforts have been successful, there are still challenges remaining, Paul said. Initiatives like the Tampa Bay Estuary Program, Tampa Bay Watch and local Audubon societies all need volunteers to protect bird nesting areas from encroachment and to pick up trash – particularly monofilament line – when there is a major clean-up effort every October, she adds.

“There’s a niche for everyone in Tampa Bay to help protect our ecosystems and our birds. Hopefully, this exhibit will show people how their individual actions can make a significant difference.”

For those curious minds wanting to learn more about the plume trade, impacts and the ladies that brought about a cultural change check our our pinterest board!