At less than an eighth of an inch, microplastics are practically invisible to the naked eye – but have been found in every water sample analyzed for microplastics in Tampa Bay over the last two years.

The most recent data (not yet published in a peer-reviewed journal) also shows that nine of 10 manatees who died in Tampa Bay had either plastic or microplastics in their digestive tracts. Additionally one of every 82 copepods – tiny filter-feeding crustaceans near the bottom of the food web – had microplastics in their guts.

The study by Eckerd College professors and students is the first step in what bay managers hope will become a long-term monitoring process. The goal is to document when and where microplastics are found by collecting samples from various sites.

Over time, researchers want to identify both the primary sources of microplastics and the potential impacts to the health of wildlife and humans. Microplastics are typically broken down into three categories:

- beads from personal care products and nurdles

- fragments that have broken down from larger pieces of plastic

- fibers from plastic-based clothing or recreational equipment.

First funded by a Bay Mini-Grant from the Tampa Bay Estuary Program with ongoing funding from the Tampa Bay Environmental Restoration Fund, This study is among the first of its kind in the nation with funding through an estuary program, according to Nancy Laurson, national estuary program coordinator for the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. “I don’t know of any other national estuary program that has this baseline when it comes to microplastics,” she said. “It’s impressive.”

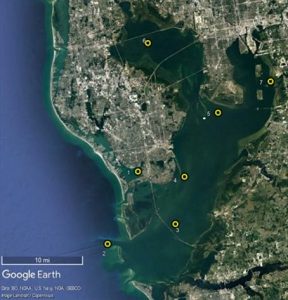

The data includes bi-monthly sampling of seven locations in the bay (including one at the mouth) taken with buckets from surface waters. They also include net tows that filter thousands of gallons of water at the surface to collect plastic and microplastic pieces.

“Surprisingly, the individual samples show little difference in concentration of microplastics between areas of the bay with limited circulation and highly developed watersheds, including Boca Ciega and Old Tampa Bays, and areas near the Gulf of Mexico,” said Amy Siuda, assistant professor of marine science. “We did expect to see more differences because of the surrounding watersheds, but that’s not what happened,” she said.

The main difference was how many plastic particles were found during the dry winter and spring compared to the wet summer. “In hindsight, this pattern was predictable based on larger quantities of stormwater carrying plastic debris into the bay during the summer storm season,” she added.

“The net tows also show significant differences, probably based upon whether they were run through one of the floating mats of shedding seagrasses that collect intermittently in the bay,” said Shannon Gowans, professor of marine science and biology. “We don’t know if it’s because of the conditions that cause the seagrass to collect or if the plastics are actually accumulating in the seagrasses before they are uprooted.”

The tows, she adds, are straight one-third mile runs with no deviation from the planned track to avoid or go through seagrass mats.

Once samples are collected, they are split and stained with a fluorescent dye so students can view them microscopically. “Without the stain,” Siuda adds, “it would be almost impossible to discern plastics from the more-numerous plankton or suspended sediments.”

That challenge — combined with less precise sampling methods — is why earlier studies likely overestimated the amount of microplastic fibers in the bay. “Fibers are much easier to see than microplastic fragments,” said Siuda.

The latest study also looks at the potential for wildlife to ingest microplastic pieces. Copepods, or small crustaceans that serve a critical role in the estuarine food web, were collected from the water samples, “digested” and stained. “The results here were different than what had been seen in previous studies elsewhere,” Gowans said. “There were higher counts in other places but that’s probably because they were looking at larger copepods – smaller copepods like the ones we see in Tampa Bay would only be able to feed on smaller pieces of plastic.”

Researchers also were able to partner with the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission to measure the consumption of microplastic particles in manatees, using the carcasses of animals that have died from, in many cases, unrelated causes. Eckerd received samples from five sections of the digestive tract ranging from the stomach to the colon.

One manatee, which tested clean for microplastics, was actually found with a big ball of fishing line. “FWC reported that 10 or 11 percent of manatees were found with pieces of plastic big enough to feel and see over the past 20 years,” Gowans said.

“While there weren’t a lot of microplastics pieces discovered in each individual, these tiny plastics were probably ingested as the manatees grazed, either in the water or attached to seagrasses,” Gowans said. “We still don’t know what potential toxicity microplastics may have on manatees, other wildlife or even human beings.”

The study will continue at least through the end of this academic year with the goal of creating a long-term monitoring program, although a specific source of funding has not been identified.