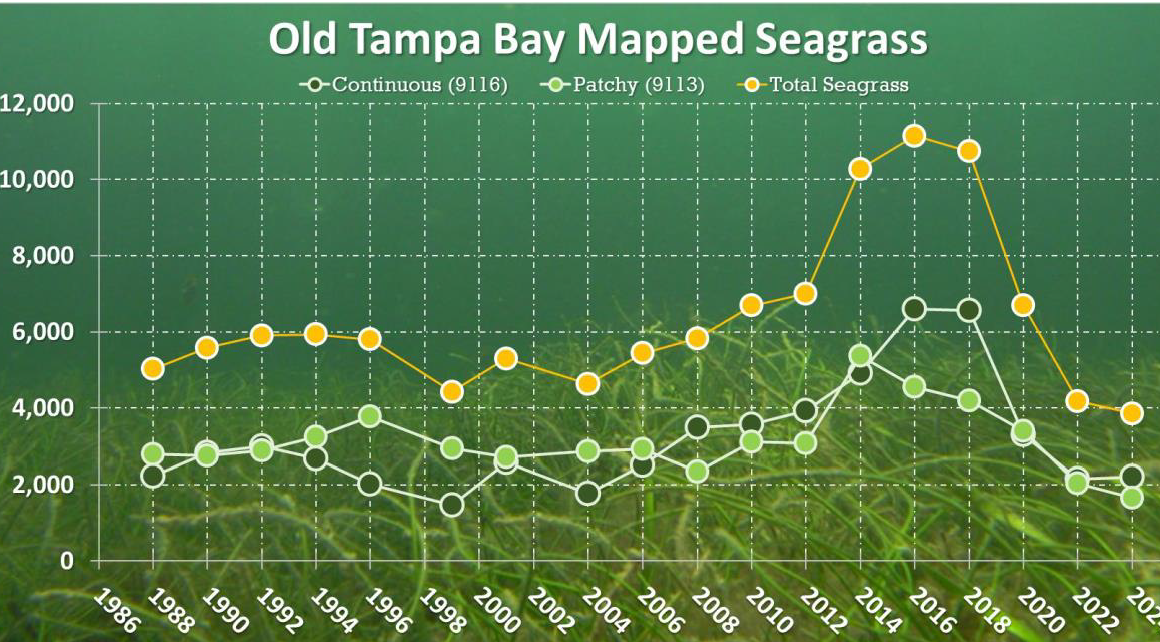

Old Tampa Bay, the segment north of the Gandy Bridge between Pinellas and Hillsborough counties, has long been the region’s “problem child.” More than half of the seagrasses lost across Tampa Bay since 2016 vanished from Old Tampa Bay, and the latest report shows that seagrass acreage is at its lowest level in more than 30 years.

The original management strategy for the bay’s recovery, created in the 1990s, recognized that restricting nutrients would limit the growth of algae, allowing enough sunlight to reach the bay bottom for seagrasses to grow where they had been in the 1950s. Until 2016, that effort made Tampa Bay an international success story.

“The original paradigm was intentionally simplified,” said Maya Burke, assistant director of the Tampa Bay Estuary Program. “We need to reconsider the way we measure nutrient loading, and it will have real consequences for local governments.”

Updating that paradigm to reflect current realities and scientific advances starts by recognizing that rainfall has significantly increased since the historic reference period in the early 1990s. The original regulatory threshold for hydrologically adjusted nitrogen loadings has been met for the last 10 years. However, significantly higher levels of rainfall meant that excess nitrogen was discharged into Old Tampa Bay for seven of those years..

Looking back, changing that threshold to measure total nitrogen loadings would mean that local governments would have needed to reduce nitrogen by an average of 83 tons per year between 2012 and 2021, but up to 150 tons in rainy years. “That’s a heck of a lot of nitrogen and it requires significant investments to capture,” Burke said.

An assimilative capacity study now underway will help determine which management actions would bring Old Tampa Bay back from what could be a tipping point. TBEP’s Tampa Bay Nutrient Management Consortium and its Technical Advisory Committee, the Tampa Bay Regional Planning Council’s Agency on Bay and Coastal Management, and state and federal regulators are currently working together to determine which management actions will be needed.

The consortium, which includes businesses, industries, and local governments, is committed to bringing Old Tampa Bay back to health. “We’ve had one-on-one meetings with the entities discharging into Old Tampa Bay, mainly local governments like cities and counties,” Burke said. “They all agree that the marginal condition of Old Tampa Bay is not acceptable, and many think that regulatory requirements will be needed to generate the political will for the necessary investments.”

While the total nitrogen loadings to Tampa Bay – 486 tons per year – hasn’t changed, permit holders must meet those thresholds in order to stay in compliance “We can’t predict rainy years, and it is very likely that permittees may be out of compliance during wet years,” Burke said. “That will make it even more important for them to report on load reduction projects that demonstrate reasonable assurance to state regulators.”

With an average 83 tons of nitrogen – or 11% to 63% of total loadings depending upon rainfall in the 2012 to 2021 period – to be removed from Old Tampa Bay, there’s no silver bullet, and managers are considering a wide range of options:

· State regulations will require that all non-beneficial wastewater discharges to surface waters must be eliminated by 2032. If fully implemented, it would remove about 92 tons of nitrogen every year, but the legislation does provide some loopholes, including the expanded use of reclaimed water that could potentially be released as it is used.

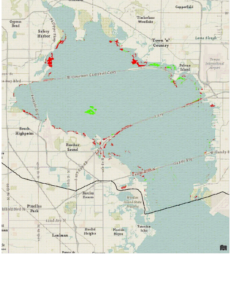

· A multi-jurisdictional study to identify and implement improvements to stormwater flowing into Old Tampa Bay is currently underway with funding through the RESTORE Act.

· Tampa Bay Water (TBW) has proposed building a reservoir near the Lake Tarpon outfall for use as potable water that would reduce freshwater inflow into Old Tampa Bay. TBEP supports that proposal, noting that TBW’s withdrawals from the Alafia River are among the most significant nitrogen load reduction projects in the region.

· The three causeways spanning Old Tampa Bay – Courtney Campell to the north, Howard Frankland across the center, and Gandy at the segment’s southern border – all significantly impede tidal flow, but significant revisions to those causeways are not planned. They could be helpful in the future, based on a 2018 project that improved water quality by increasing flow.

· Oyster restoration projects hold some promise, particularly in reducing the negative impacts of the annual Pyrodinium blooms that have occurred annually since 2000, although large-scale testing is still years away.

“What we’ve seen in the Old Tampa Bay segment is an insufficient number of projects that can remedy the loss of seagrasses,” Burke said. “The problem is that, from a nitrogen loading perspective, we are meeting state regulatory thresholds because compliance is assessed based upon a hydrologically normalized load that was established using rainfall measured 30 years ago. We are periodically out of compliance with the chlorophyll-a standard and the assimilative capacity assessment project suggests that chlorophyl-al is responding to actual loads more strongly than normalized ones.”

As bay managers work toward solutions, Burke stresses that none of the projects – or their costs to local governments – have been finalized. “There are no done deals – they’re all decisions that the Nitrogen Management Consortium and the community more broadly will need to weigh in on.”