But There’s Danger On The Ground

Even their names invoke romance: great blue herons, snowy egrets, glossy ibis and roseate spoonbills. And as the weather warms, approximately 50,000 pairs of shore and wading birds are expected to find love in the air near Tampa Bay. Once they mate and build a nest, though, they’ll face increasing danger on the ground.

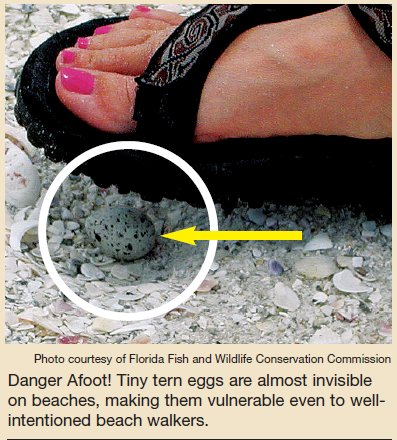

As Tampa Bay’s water quality and habitat rebounds, the region has become one of the state’s most important nesting sites. Still, birds must share their habitat with predators like raccoons, hawks and ospreys. Human intervention, even by well-intentioned people, may cause adults to abandon their nests, leaving chicks to perish in the heat or vulnerable to a fast-flying hawk.

As Tampa Bay’s water quality and habitat rebounds, the region has become one of the state’s most important nesting sites. Still, birds must share their habitat with predators like raccoons, hawks and ospreys. Human intervention, even by well-intentioned people, may cause adults to abandon their nests, leaving chicks to perish in the heat or vulnerable to a fast-flying hawk.

Education is critical, say bay managers, for both people who enjoy the bay and the limited number of on-water law enforcement officials who patrol it. A day-long workshop in March — just prior to nesting season — brought bay managers and law enforcement officers together to discuss mutual concerns.

“There are 30 species of birds that nest here – including 12 listed (as endangered, threatened or special concern) species,” noted Ann Paul, Tampa Bay regional coordinator for Audubon of Florida. “Tampa Bay is one of the most important areas in the state — at least as important as the Everglades — to these birds.”

But from a law enforcement perspective, it’s not easy for an officer charged with multiple duties to tell the difference between an endangered snowy plover and a more-common laughing gull, notes Lt. Grady Caffin of the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission’s law enforcement division. The differences, however, can be critical: while most non-game birds are protected under federal law, penalties for species listed as threatened or endangered are much stricter.

In fact, it is illegal to trespass on just one Tampa Bay site – the Alafia Banks sanctuary which is owned by Cargill and leased to Audubon of Florida. Other sanctuaries, including spoil islands in Hillsborough Bay that host more than 6000 pairs of birds every summer, aren’t strictly off-limits.

“The signs warn people that if they trespass and harm a bird or a nest, they will be breaking the law, but we can’t stop people from walking past them,” notes Nancy Douglass, regional wildlife biologist for the FWC.

“The tough part is proving harassment, because if they walk in a posted area and scare off a bird, it’s technically a violation,” adds Caffin. “But no reasonable police officer is going to court and try to articulate that point to a judge.”

In fact, it’s difficult to prosecute even when endangered birds are harassed, said Ed Lewis, special agent for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in Fort Myers. “To prove harassment, you have to prove that there was significant alteration in the normal feeding, breeding and sheltering activities. We’ll need a statement from an expert biologist that those activities were significantly altered, plus witnesses – and it would be nice to have videotape.”

Officers also must prioritize their cases, recognizing that they will be presenting them to prosecutors more accustomed to building cases against bank robbers and drug dealers, Lewis adds.

Part of the decision to prosecute involves the level of violation, adds Mary Sumner, who coordinates training for FWC law enforcement officers in southwest Florida. “It’s one thing when people pull a boat up on an island and their dog chases off nesting birds, and another to have two juveniles on dirt bikes racing over dunes after birds.”

The latter was an actual case eventually settled in pre-trial intervention. Recognizing that the boys’ fathers would have paid fines but it might not have taught the teenagers anything, “They had to maintain good grades, write a paper on why it’s important to obey wildlife laws, and spend 40 hours picking up trash in a community service program.”