COVERING TAMPA BAY AND ITS WATERSHED |

Our subscribe page has moved! Please visit baysoundings.com/subscribe to submit your subscription request. |

||||||

|

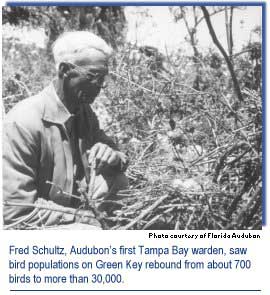

From 1934 to 1962, the Schultzes were charged with protecting a large bird colony located on Green Key, a place once described as "an enchanted isle... where trees bloom birds." By Victoria Parsons Just off the northern shore of the Fred and Idah Schultz Preserve, Whiskey Stump Key still stands, reminding visitors of the hardships the Schultzes endured living there while Fred served as the first warden of the National Audubon Society's Tampa Bay Sanctuaries. From 1934 to 1962, the Schultzes were charged with protecting a large bird colony located on Green Key, a place once described as "an enchanted isle... where trees bloom birds." They had a homestead near what is now Bloomingdale and cut down pine trees there to build at least three cabins on Whiskey Stump - one for themselves, one for visitors and yet another to replace one that had been destroyed by termites. "The fact that they were from the community made them very effective," notes Ann Paul, manager of Audubon's Florida Coastal Islands Sanctuaries. "They could talk to friends, neighbors and relatives without being perceived as carpetbaggers telling people what to do." Schultz was hired after Dr. Herbert Mills, the first pathologist on the west coast of Florida, donated funds to protect birds on Green Key. He visited the island in 1933 and described the devastation as "wanton destruction of life... with gun shells scattered around on the ground, young birds dead and alive on the ground, empty nests and other signs that birds had been killed and carried out by the sackful." By the time the Schultzes arrived on Whiskey Stump Key, the plume trade that had devastated bird populations across the country was declining, but pioneering families still hunted birds to eat and sell to fine restaurants in Tampa as "sea squab." Birds returning to their nests also were seen as ideal for target practice. "There's one story about a conversation Fred had with a friend who owned the local hardware store," Paul recalls. "The friend told Fred that they really appreciated what he and Idah were doing to protect the bids, even though sales of ammunition had dropped by 50%." Bird populations on Green Key soared, according to Mill's reports to Audubon. By 1939, he estimated populations of 30,000 individual birds - up from only about 700 in 1934. "After six years of Audubon wardenship, we proudly justify our protectorate of the Tampa Bay rookeries with an increase of 3000% in the birds of Green Key alone," Mills wrote. Shortly before Schultz was hired, dredging began on a channel to the Mosaic (formerly Cargill) phosphate facility. Fred Schultz worked with the company to protect the birds that flocked to the spoil islands and then helped set up the Alafia Banks Bird Sanctuary, said Rich Paul, former Audubon Sanctuaries manager. "At first it was just gulls, terns and skimmers but as vegetation grew, the colony at Green Key moved over to the spoil islands," he said. "The spoil islands are much larger and further offshore so it's more difficult for raccoons and other predators to reach them." At its peak, an estimated 40,000 nesting pairs of birds had colonized the Alafia Bank, helping it to become one of the state's most important nesting sites. "That's more birds than we have there now," Ann Paul notes. "The Tampa Bay sanctuaries really blossomed under Fred and Idah's care." |

|||||||

|

|||||||

|

© 2004 Bay Soundings

|

|||||||

Bird Sanctuaries Thrived Under Fred and Idah Schultz's Care

Bird Sanctuaries Thrived Under Fred and Idah Schultz's Care