COVERING TAMPA BAY AND ITS WATERSHED |

Our subscribe page has moved! Please visit baysoundings.com/subscribe to submit your subscription request. |

||||||

|

By Mary Kelley Hoppe Doug Robison is eager to dig in on a cumulative impact study he hopes will help set the record straight on environmental impacts to the Peace River. But finding conclusive answers or convincing skeptics on both sides of the validity of those findings won't be easy.

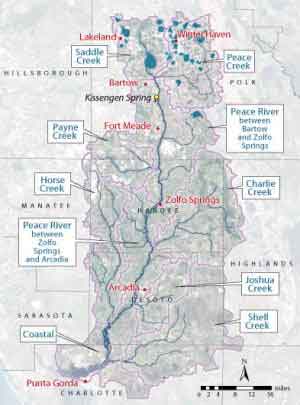

"Will we get it down to specific percentages due to this or that· probably not," says Robison, project manager for PBS&J, the firm hired to conduct the cumulative impact study mandated by the Legislature in December 2003. But the study should reveal what's having the most significant impact in each river sub-basin, Robison says. Most importantly, the study has been designed to tease out cumulative and incremental impacts from all watershed land uses, from urban development and mining to intensive agriculture. Results, due next March, will be used to develop a resource management plan. The $750,000, year-long study was commissioned by Florida Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) and the Southwest Florida Water Management District (SWFWMD). In addition to evaluating changes in land use going back to the 1940s, factors responsible for those changes and associated impacts on water resources, the final report also calls for an analysis of regulatory effectiveness over time - and attempts to correlate regulatory action or inaction to things like wetlands loss or reductions in river flows. While several studies have examined environmental conditions and causes in the Peace basin, this is the first cumulative impact assessment, says Robison, and the first attempt to bring all the data together in one place and analyze it. One of the most hotly debated issues is what's behind declining flows on the Peace River, which flows 105 miles from its headwaters near Lakeland to its terminus at Charlotte Harbor. Water from the Peace is vital to the health of the downstream estuary and its renowned sport fishery, and also supplies drinking water for tens of thousands of area residents. Peace River flows have declined steadily since the early 1960s. The causes are complex. While groundwater withdrawals for public supply, agriculture and mining have all contributed, SWFWMD Director Dave Moore says long-term rainfall may be responsible for as much as 90% of the reduction in river flows. "When you look at the Peace River at Arcadia from 1960 to the 1990s, the river declined by about 45%," says Moore. "We looked at every stream in Florida - the Withlacoochee was down 47%, for example. It turns out that there is a long-term rainfall signature not only through Central Florida but throughout much of the Atlantic basin. "What really makes that point is when you overlay the long-term average runoff from Joshua Creek, where there's been virtually no mining, with runoff from the Haynes Creek basin, which has been heavily mined. There's very little difference.

"That's not to say there haven't been impacts from all of our land uses, but you need to be able to factor out natural variables from manmade impacts," Moore says. "I don't buy it," says Charlotte County Commissioner Adam Cummings, who has led the fight against mining expansion in the region. For three years in a row, Cummings says, a section of the Peace River would run dry when water was flowing upstream and downstream. "They were giving walking tours - walking being the operative term because there was no floating. The water started where mining stopped. The only dry section was the section being mined. You don't dry up part of the river and chalk it up to lack of rainfall," Cummings says. "The answer is it's probably both things," says Tony Janicki, an expert in water quality modeling and assessment who has testified on the effect of mining on water quality and streams. "There's no doubt that the amount of rainfall is a factor. There's also no doubt that a lot of the watershed hasn't been put back as well as it should - and we're losing a lot more water than necessary." Cummings suspects that over-pumping the aquifer caused sinks to form, then when water flowed down the river it dropped through holes in the karst or underlying limestone.

"The scariest part of strip mining, the one thing they can't fix," Cummings says, "is when you mix up the soils, when you tear out the underground plumbing upon which everything else depends, you can't put it back." Historically, adds Janicki, there have been some very significant water quality impacts, but the ditch-and-berm system (used to capture runoff from the mine), if done correctly, can preclude problems during mining. Impacts are more likely to occur after mining when stream restoration is attempted. It comes down to the soils, he says. And so it goes with the ongoing search for answers. "Underneath it all - literally underneath it all - are the answers to all these questions," says Janicki. "If you don't get the soils right, the hydrology's not right, and the water quality's not right." |

|||||||

|

|||||||

|

© 2005 Bay Soundings

|

|||||||

Who's Disturbing the Peace?

Who's Disturbing the Peace?