the colored half-tone of a Florida-sunset appeared on the cover of his landmark book.

There’s no lost quite like Florida lost. Whether on land, on water, or somewhere in the many gradations between, our state, for all its extraordinary growth, is still rich in opportunities to get swamped, chomped, stuck, sunk, tangled, or just plain turned around.

By Amanda Hagood

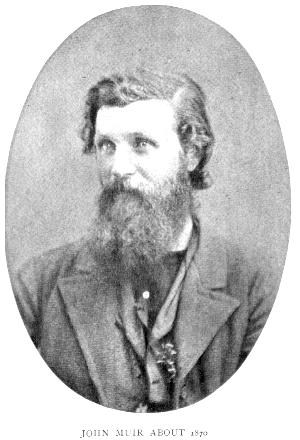

Anyone who has ventured off Florida’s beaten paths knows this, as much today as it was in the 1860s, when tourists first steamboated down the St. Johns and Ocklawaha rivers to Silver Springs in pursuit of a warm climate and healing waters. Though most of these early snowbirds took the water route, John Muir, a self-styled botanical pilgrim from Indiana, took to the trail (such as it was) in the fall of 1867, in search of what he called a “flowery Canaan” in Florida’s savannas and swamps. Picking his way along the path of David Yulee’s Florida Railroad, Muir walked 170 miles from Fernandina to Cedar Key, an epic tramp captured in his posthumously published A Thousand-Mile Walk to the Gulf (1916).

Years after his Florida journey, Muir would write of extraordinary treks in California’s High Sierra and among Southeast Alaska’s glaciers, as well as founding the Sierra Club — which was originally dedicated to mountain rambles. It is no overstatement to say he pioneered the modern concept of hiking.

But even this prodigious walker found Florida’s terrain a challenge. Snared in profusions of briars, haunted by visions of prowling gators and the echoing calls of owls, and caught in seemingly endless stretches of swamp, Muir suffered doubts along his Florida sojourn that were nothing short of existential. Reflecting, for instance, on the “creeping” progress of Florida’s rivers, so different from the well-defined “banks and braes” of his home terrain, he despairs in his journal of October 20: “No stream that I crossed to-day appeared to have the least idea where it was going!”

There may have been an element of introspection here. At this point, Muir had been walking for almost two months, having started his trek in Kentucky. His botanizing quest transformed into a survival march through an increasingly unforgiving country, as plagued by the ills of post-war poverty, violence, and disease as much as it was by creatures (and sometimes plants) that bite.

This uncertainty would come to a head when Muir finally reached Cedar Key, only to discover that he had come down with a case of malaria. As he recovered over the next few months in the home of a local sawmill owner, he abandoned his grand plans to extend his trek through South America.

But then again, who among us has not gone a bridge or a bend too far when it comes to hiking or paddling through Florida’s labyrinthine terrains? When I read Muir’s account, I find myself right back in the middle of many sweat-soaked moments when it was clear I was no match for wild Florida.

There was the broiling summer paddle through a preserve when we paused, mouths dry and everything else wet, under a snaky-looking tree for a drink—only to discover we were down to a single growler of very warm beer. There was the swim off Honeymoon Island—our first real experience with red tide—when we breezily ignored the posted signs about dead marine life and found ourselves surrounded by not one, not two, but dozens of fishy carcasses.

Then there was the sun-bleached Labor Day visit to Egmont Key, where we laughed at our ferry captain’s warnings about the lack of facilities, the heat, and how some foolish visitors end up “waiting under the dock” hours before the boat returns just to escape the powerful sun. After two hours of wandering the island in search of a beach not given over to bird sanctuaries or holiday boaters, can you guess where we ended up?

But even in our most disconsolate wanderings, we find moments of beauty and inspiration. This was certainly the case with Muir, whose account is sprinkled with ecstatic encounters with plants. My favorite is his “first palmetto,” which he encountered shortly after leaving Fernandina.

“This vegetable has a plain gray shaft, round as a broom-handle,” he notes, “and a crown of varnished channeled leaves. It is a plainer plant than the humblest of Wisconsin oaks; but, whether rocking and rustling in the wind or poised in thoughtful calm in the sunshine, it has a power of expression not excelled by any plant high or low that I have met in my whole walk thus far.”

Utterly fascinated by the play of “tropic light” reflecting off its fronds “in sparks and splinters and long-rayed stars,” Muir finds not only a new plant, but a deep sense of gratitude: “I thank the Lord with all my heart for his goodness in granting me admission to this magnificent realm.”

And even without such guiding stars, getting lost can be a positive experience that leads to growth or, as psychologist Alan Castel describes it, a “most rewarding form of deep discovery.” In a time when GPS technologies are literally at our fingertips, we have come to rely on a navigational strategy of piecing together landmarks and steps. This is certainly effective for getting from point A to point B, assuming point B has been plotted accurately—and I’m sure we all have stories about arriving in some rather surprising places thanks to our maps app. But following this strategy often provides us with little or no sense of what lies between origin and destination, leaving us disoriented when it comes to finding points nearby. To paraphrase Gertrude Stein: there is no where there.

An alternative strategy is creating the map ourselves through a cumulative exploration of an area. As we turn and return, trying new paths and encoding new spatial information into our brains all along, we begin to understand the relationship of landmarks and features in a field, eventually learning to navigate in new ways—those paths which become our shortcuts, detours and favorite scenic routes.

A recent study conducted by neuroscientist Eleanor Maguire at the University College London indicates that this kind of spatial problem-solving can quite literally be a growth experience: Maguire looked at the hippocampus (a small structure involved in the formation of new memories) in the brains of London taxi drivers who were studying to pass their licensing tests—a notoriously difficult feat which requires them to memorize about 25,000 streets, otherwise known as “the Knowledge.”

Amazingly, she found not only that taxi drivers tended to have significantly larger hippocampi than non-taxi drivers (including bus drivers), but also that their hippocampi actually grew during the four-year period during which they prepared for the test. This suggests that getting lost—and finding our way again—changes us, and our relationship to a place, in profound ways.

The journey through Florida was certainly a turning point for Muir, who left with a deeper, less anthropocentric conception of the relationship between humans and the natural world—one that would deeply influence his belief in wilderness preservation. I believe our own Florida rambles do the same for us.

As Rebecca Solnit writes, “I like walking because it is slow, and I suspect that the mind, like the feet, works at about three miles an hour. If this is so, then modern life is moving faster than the speed of thought or thoughtfulness.”

So, with all due respect, I say: go get lost, while there are still some places to get lost in. Maybe just bring some extra water along with you.

Amanda Hagood lives in Gulfport and teaches courses in environmental humanities at Eckerd College. Her work has been published in Interdisciplinary Studies in Literature and the Environment, Salt Creek Journal, and Environmental Humanities. Her favorite hike in Florida is still her first: a visit to Boyd Hill between appointments looking for a place to live. She and her partner were a little dispirited because none of the options were great. “But then we spent one hour walking the trails there and I said, ‘I don’t care where we sleep, can we just be sure to come here every day?’ And they ended up renting a lovely little house just a couple blocks away.

Image Caption:

Hagood and her son Jaime hiking a Florida trail.