By Joseph Bonasia, chair of the Florida Rights of Nature Network

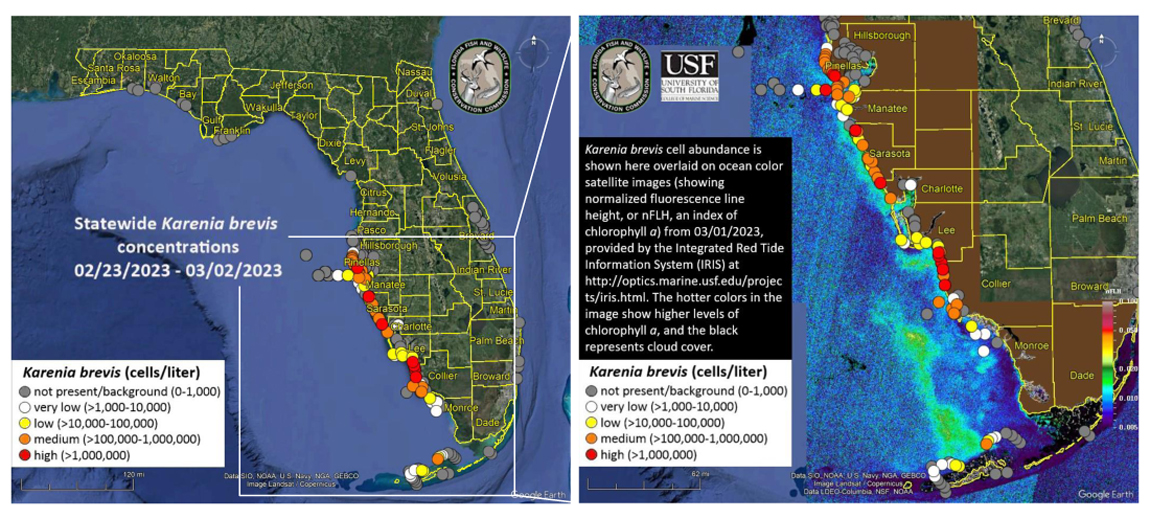

Red tide is again plaguing southwest Florida from Pinellas to Collier counties. No one should be surprised.

It’s a naturally occurring phenomenon, and from 1878 to 1994 there were 64 months of red tide documented in Florida. However, from 1994 to now – just 28 years – we’ve had over 200 months. Research shows that pollution is a significant part of the problem.

If this were Florida’s only water quality issue, maybe Florida wouldn’t need a constitutional “Right to Clean and Healthy Waters.” But even a partial list of facts demonstrates the broad failure of our environmental regulatory system:

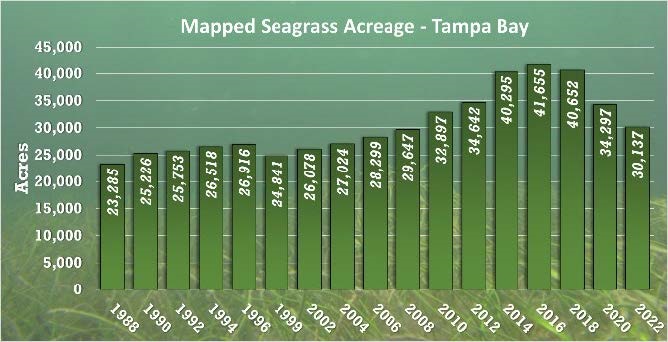

- The Indian River Lagoon has lost 58% of its seagrass, or 46,000 acres, since 2009. Tampa Bay has lost more than 30% of its seagrasses, or 11,599 acres, since 2016.

- Eighty percent of Florida’s 1,000 artesian springs are polluted.

- Nearly a million acres of estuaries and 9,000 miles of rivers and streams are contaminated with fecal bacteria.

- Blue-green algae blooms are increasingly common and are linked to neurodegenerative diseases.

- No state has more acres of polluted lake water than Florida.

- No state has lost more acres of wetlands than Florida, 9.3 million.

The way to solve our water problems, some people say, is not through a Florida constitutional amendment, but through the legislative process and through carefully crafted regulations by state and local agencies, where science determines environmental policy.

If only the system worked that way.

In 2015, water district managers in South Florida were ready to crack down on agricultural pollution when, at the last minute, they let a sugar lobbyist dictate edits to a report that paved the way for weaker regulations. The final policy took polluters at their word regarding environmental safeguards and held no one accountable if water quality suffered.

“The sugar lobbyist’s influence,” the TC Palm reported, “exceeded that of scientists, environmentalists and the general public, [and] affected changes to rules meant to protect Florida waterways from pollutants that feed toxic algae blooms.”

In 2020, 89% of Orange County voters passed a Right to Clean Water County Charter Amendment. The Florida Legislature, however, preempted the authority of local governments to pass laws that give rights to nature or citizens any rights to the natural environment. A single sentence, buried in line 2371 of the 2020 Clean Waterway Act, prohibits local governments from granting “any legal rights to a plant, an animal, a body of water, or any other part of the natural environment,” or granting any citizens “any specific rights relating to the natural environment not otherwise authorized in general law or specifically granted in the State Constitution.”

At the outset of his first term, Governor Ron DeSantis created the Blue-Green Algae Task Force comprised of nationally recognized scholars that would “ensure that objective and sound science informs Florida’s environmental decision-making process.” But after four years, only 13% of task force recommendations have been implemented by the legislature. Why?

Special interests too often have undue influence over environmental policy. This problem isn’t unique to Florida.

In 2012, Pennsylvania lawmakers passed Act 13. Under this law, a municipality would have had no authority to prevent fracking operations next to schools or in church parking lots, for example, and doctors couldn’t speak publicly about health impacts to their patients. Act 13 was written by industry lawyers, not the elected legislators who approved it, and Pennsylvania’s governor had received $1.7 million in industry contributions.

Several towns filed suit contesting the law, and in 2013, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court declared key provisions of Act 13 unconstitutional. Critical to that decision was the Environmental Rights Amendment to the Pennsylvania Constitution, which, among other things, states, “The people have the right to clean air, pure water, and to the preservation of the natural, scenic, historic, and aesthetic values of the environment.”

“It is not” the court said, “a historical accident that the Pennsylvania Constitution…places citizen’s environmental rights on par with their political rights.”

Floridians deserve a right to clean water on par with our fundamental political rights, such as the freedom of speech and the right to bear arms if we are to bring systemic change to a flawed regulatory system. With a fundamental “Right to Clean and Healthy Waters (RTCHW)” constitutional amendment, we can hold the state government accountable when its action or inaction permits pollution and degradation of our waters and aquatic ecosystems.

For example, red tides and blue-green algae blooms in Southwest Florida are greatly exacerbated by water releases into the Caloosahatchee River from polluted Lake Okeechobee. Spending billions of taxpayer dollars to clean polluted water after the fact is not the best solution to this problem. Commonsense says stopping pollution at its source is.

Thirty-two water basins surrounding Lake Okeechobee exceed state pollution limits. With a “Right to Clean and Healthy Waters,” we could hold the state accountable through the court system, which, informed by the science, could compel the FDEP to meet the water quality standards. As a judge recently ruled in New York’s first green amendment case, “Complying with the constitution is not optional for state agencies.”

In 2008, the Army Corp of Engineers, after scientific analysis, issued a report that predicted disaster if the FDEP allowed owners of the Piney Point phosphate plant in Manatee County to store dredged material from Port Manatee. Armed with that report and a right to clean water, the courts could have compelled better decision-making on the part of the state, thus avoiding the release of 212 million gallons of polluted water into Tampa Bay.

For the RTCHW to qualify for the 2024 ballot, 891,589 signed and verified petitions are needed by November 30, 2023. Before that, 223,000 are needed to trigger a Florida Supreme Court review. Our goal is to achieve that by April 22, Earth Day, but it won’t happen if Floridians don’t make it happen.

Registered Florida voters should print out, sign, and mail the petition and encourage their family and friends to do the same.

If you don’t feel any sense of urgency, HB 1197, “Land and Water Management,” and a companion bill, SB 1240, have been filed for the current legislative session by two Tampa Bay legislators, Danny Burgess of Zephyrhills and Randy Maggard of Dade City. If passed, the legislation would prohibit all counties and municipalities from adopting laws relating to “water quality, quantity, pollution control, pollution discharge prevention or removal, and wetlands.”

Floridians need a fundamental “Right to Clean and Healthy Waters” ASAP.

Joseph Bonasia is chair of the Florida Rights of Nature Network. The views and opinions expressed in this column are those of the author’s and do not necessarily reflect the views or positions of the Tampa Bay Regional Planning Council.

Some of the statements included in this article could not be hyperlinked, but the references are noted here:

- Page 93 of A Toxic Inconvenience, by Nicholas G. Penniman, published in 2019.