From a lab experiment gone wrong to a secret government operation, how forever chemicals went from revolutionary invention to pervasive menace.

By Jessica Sirois

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), also known as “forever chemicals,” have been making headlines as evidence of their health and environmental impact mounts. What many people don’t know is that their creation was a complete accident.

In the 1930s, a group of DuPont chemists trying to invent a new refrigerant instead created a mysterious white substance that could withstand high temperatures and corrosive acids, that was later named Teflon. Not knowing how to scale the product for use, it remained in their labs until the U.S. government invested heavily in its production as part of the Manhattan Project, developing the world’s first nuclear weapon during World War II. Teflon was essential to the project because it did not react with the caustic substances generated during the uranium enrichment process.

With the production infrastructure in place, after the war,Teflon was used to create innovative products like nonstick cookware and waterproof clothing. Seeing the demand for these substances, the company 3M began upscaling its production, leading to the class of PFAS substances we have today.

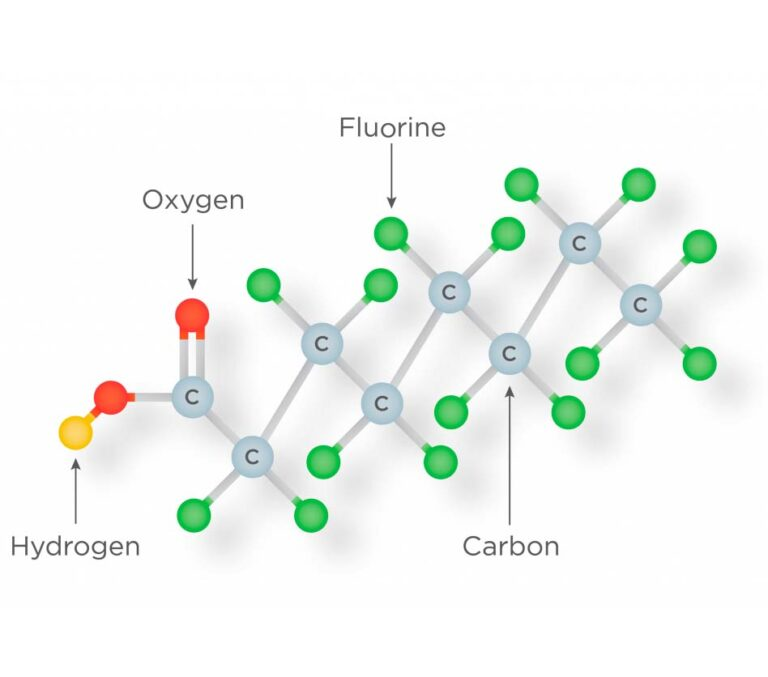

A class of synthetic fluorine-based compounds, PFAS have strong chemical bonds, making them resistant to environmental degradation, water- and oil-repellent, corrosion-resistant, and capable of withstanding high temperatures. Their “usefulness” led to the incorporation of PFAS in everything from fire-extinguishing foam and fertilizers to fast food wrappers, waterproof clothes, furniture and even makeup. PFASs do not break down and persist in the environment, hence their nickname “forever chemicals.” Researchers have detected PFAS in air, drinking water, food, blood, and even breast milk.

Health risks of PFAS exposure include increased cholesterol, reduced antibody response to vaccines, decreased fertility, developmental delays in children, and increased risk of cancers such as prostate, kidney, and testicular cancers. With over 14,000 chemicals in the PFAS class, scientists are only scratching the surface on the ways PFAS impact our health and the environment.

Of course, 3M and DuPont were aware of the health risks PFAS posed as late as the 1960s, and kept them a secret. Mariah Blake’s striking new book They Poisoned the World: Life and Death in the Age of Forever Chemicals details how their coverup was finally exposed thanks to everyday citizens who sued DuPont and, in the process, uncovered proof that DuPont and 3M had known about the toxicity of PFAS for decades.

Since then, lawsuits have skyrocketed. Recently, 3M and DuPont collectively reached a settlement to pay $13.6 billion for contaminating public water systems across the country. Tampa Bay Water, which supplies water to more than 2.6 million people in the Tampa Bay region, was awarded $21 million from this settlement. These funds can help public water utilities monitor and address PFAS contamination but they must have filed a claim by January 1, 2026.

Recently, European researchers developed a technique to detect the smallest class of PFAS in water, ultra-short-chainPFAS. The results were alarming. More than 98% of the PFAS present were ultra-short-chain PFAS with trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) the most common.

TFA is a byproduct of over 2,000 larger PFAS and is highly mobile and water-soluble, making it the most widespread and pervasive PFAS on Earth. It is more abundant than all the forever chemicals we are monitoring combined. Due to its small size, the water filtration systems currently being installed in communities for larger PFAS do not remove TFA. Preliminary studies have indicated adverse effects of TFA on liver function as well as potential reproductive toxicity.

Shockingly, the EPA does not define TFA as a PFAS because it has less than two adjoining fluorinated carbon atoms, a definition shared by industries rather than the scientific community, which defines PFAS as any chemical compound with one fluorinated carbon atom. This means TFA is not being tested for or regulated in the US, even though it spreads farther, builds up faster in crops, and passes through filters.

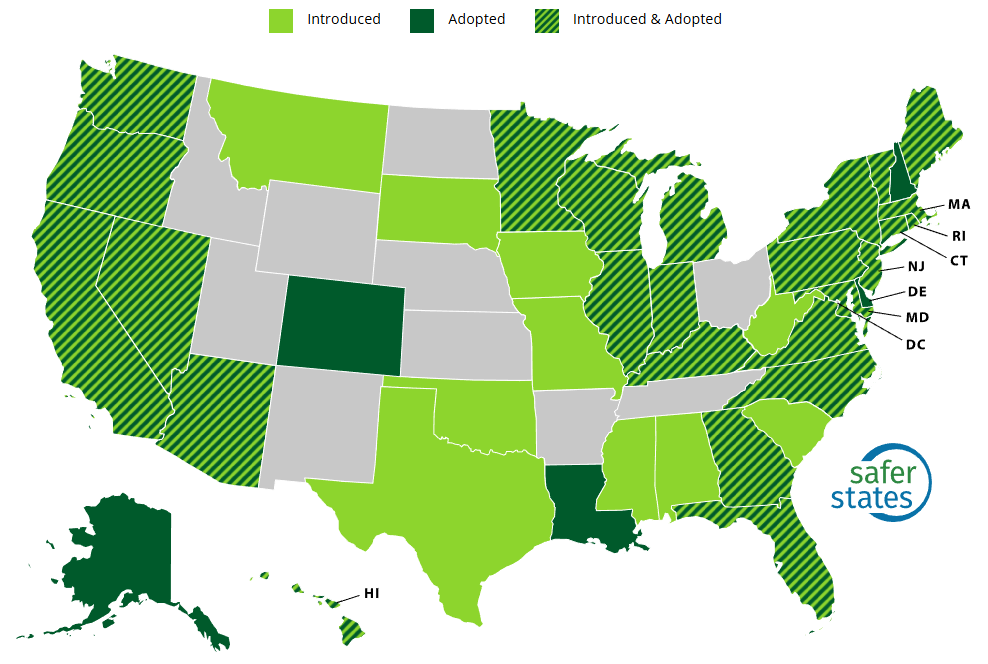

As federal regulations to manage PFAS stall, many states are adopting their own. So far, 30 states have adopted policies including prohibiting PFAS in firefighting foam, biosolids, children’s products, food packaging and cosmetics. In Florida, bills to regulate PFAS in firefighting foam and cosmetics failed to pass and were withdrawn from consideration. Current PFAS laws only provide funding for testing, remediation, and to homeowners with private wells contaminated by PFOA or PFOS.

The Safer States Bill Tracker has documented 30 states that have adopted policies regarding PFAS.

However, local governments are also stepping in. San Francisco passed an ordinance prohibiting PFAS in firefighter gear and Fort Worth, Texas passed one requiring industrial facilities to reduce PFAS levels in discharged wastewater within a year of detection.

Approaches at all levels are necessary to mitigate this global epidemic, and resources such as the EPA’s PFAS Analytical Tools, the Environmental Working Group’s PFAS Contamination Mapper, and Safer States’ Bill Tracker can help. They can provide public water utilities with data for filing claims to fund testing, and help local governments create tailored policies to reduce PFAS exposure within their own communities, as well as making that information accessible to private citizens.

As lawsuits mount and more PFAS like TFA inevitably come under scrutiny, coordinated testing and monitoring at a local level can make it easier to apply for funding as it becomes available when industries are held accountable for poisoning the world.

Jessica Sirois is a Science Policy Fellow through the National Academies’ Gulf Research Program, working with the Tampa Bay Regional Planning Council. She is passionate about working at the intersection of environmental and social studies to find community-led solutions to ecological challenges.

This is part one of a three-part series on PFAS. Part two will focus on PFAS found in the Tampa Bay region, and part three will include tips on how to avoid these very common but highly dangerous substances.

Originally published January 8, 2026