As the highly pathogenic avian influenza – also known as bird flu – sweeps through Florida, experts aren’t yet recommending that backyard birders pull in their feeders to prevent the spread of the dread disease among their beloved songbirds.

“There’s no official recommendation to take down feeders,” said Mark Cunningham, diagnostic veterinarian manager for the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission. They do suggest that feeders and bird baths are cleaned and disinfected every week to 10 days, but that’s a long-standing recommendation to prevent salmonellosis and other diseases, not a new recommendation to prevent bird flu.

The important exception to that rule is for people with backyard poultry like chickens or quail, Cunningham adds. “You don’t want to attract wild birds if you have backyard poultry, and you should keep bird feeders and baths far away from them.”

The virus spreads through saliva, nasal secretions and feces, with feces considered the primary mode of infection. Mortality rates range from 90% to 100% in chickens, but it is probably much lower in wild birds.

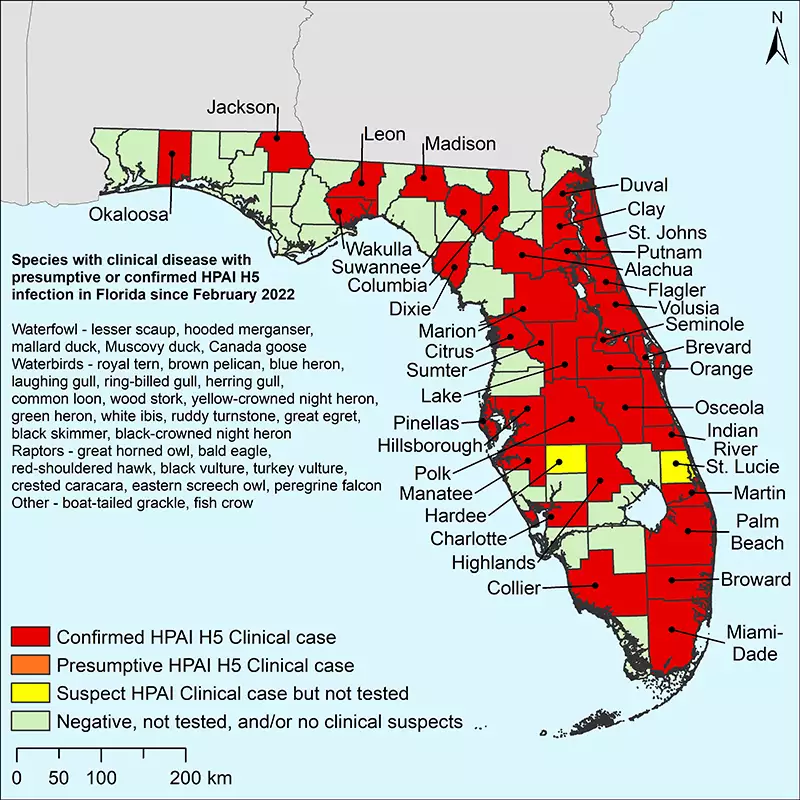

The Eurasian strain of bird flu – officially known as H5N1 – was documented in Europe in early 2021, then spread to the U.S. over the fall and winter. The first Florida cases were documented in January 2022 in hunter-harvested blue-winged teal in Palm Beach County. Since then, bird flu has been confirmed in 35 of the state’s 67 counties including Hillsborough, Pinellas, Polk and Manatee. To date, it has only been confirmed in one species of songbird – the boat-tailed grackle – although it has been seen in songbirds in other parts of the country, and could potentially become an issue here. “This disease is pretty rare in songbirds but it does occur,” Cunningham notes.

Some cases are totally asymptomatic, but concerned birdwatchers should look for birds with neurological problems such as a lack of coordination, seizures or twisting their heads from side to side. Dead birds, with no signs of trauma, should be reported to https://myfwc.com/research/wildlife/health/avian/influenza/

Sick or dying birds should be handled carefully. Human infections of avian influenza are very rare but they can happen when the virus gets into a person’s eyes, nose or throat, according to the Centers for Disease Control. Your pets, including dogs and cats, can be infected if they eat diseased birds, although it is not a common occurrence.

Wild Birds at Risk

The birds most likely to be infected include black vultures and Muscovy ducks, although raptors like bald eagles and peregrine falcons as well as some other ducks can be infected. “It’s birds that eat and poop in the same place, along with birds that eat those diseased birds,” said Nancy Murrah, president of the Raptor Center of Tampa Bay who has been dealing with the impact since early this year.

“Every black vulture we’ve sent in to be tested came back positive,” she says. “And we had a peregrine falcon test positive because those birds eat ducks.”

The nearly-inevitable death is awful, she said. “Their heads are hanging and they’re having seizures that are horrible to watch – it’s even worse than rat poison.”

Additional Resources:

Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission: MyFWC.com/AvianInfluenza

Florida Department of Health: floridahealth.gov/diseases-and-conditions/influenza/index.html

Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services: fdacs.gov/Consumer-Resources/Animals/Animal-Diseases/Avian-Influenza