Although often invisible to the naked eye and frequently vilified for the problems they cause, algae may be the most important critters in the world.

“The oxygen in every second breath we take comes from algae,” says Alina Corcoran, head of the harmful algal blooms research subsection at the Florida Fish and Wildlife Research Institute. “Algae use carbon dioxide and release oxygen — if it weren’t for algae, the world as we know it wouldn’t exist.”

Algae range from single-cell phytoplankton to giant kelp that grow to more than 100 feet. Like plants that grow on land, algae use photosynthesis to turn sunlight and carbon dioxide into energy and become the base of a food web that supports the entire aquatic ecosystem.

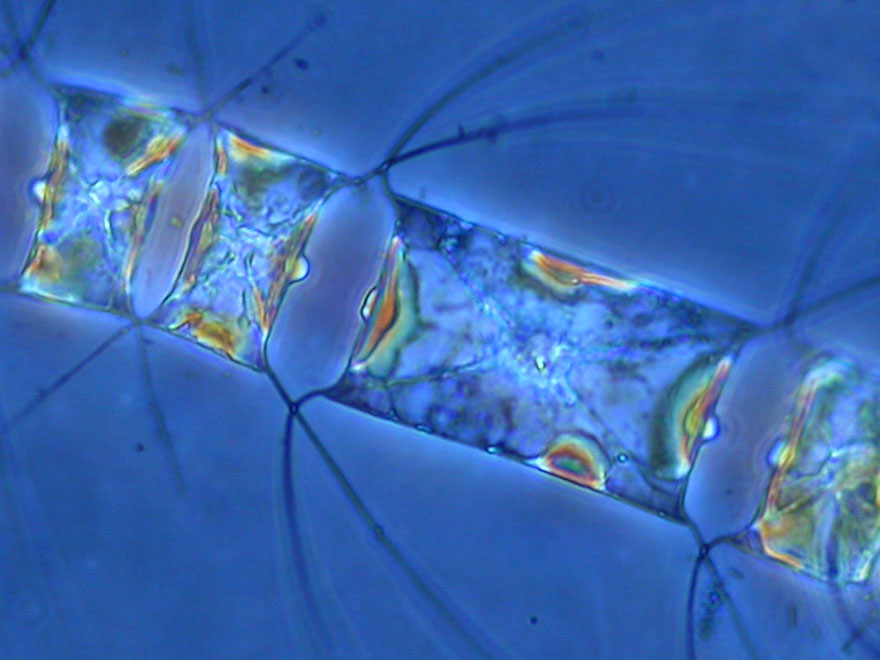

And like land plants, they’re incredibly diverse, having evolved over billions of years to take advantage of niches in the ecosystem. Some need saltwater, others won’t survive in it. Even in the same environment, different algae absorb different frequencies of sunlight so they can all grow successfully together. Some drift wherever currents take them, while others can swim short distances. Algae have different growth patterns as well – some grow so fast they need few defenses against predators but others, like certain diatoms, use glass houses built out of silica they absorb from water as protection.

Algal Blooms Create World-Wide Problems

[easy-media med=”274″ size=”250,250″ align=”right”]While most algae are either beneficial or benign, there are always some problem children in a large family. Although about 50 species that form “harmful algal blooms,” or HABs, are known to live in Florida, Karenia brevis – aka Red Tide – is the poster child for HABs. Scientists still know little about its lifecycle. What they do know is that during blooms, K. brevis releases toxins that make humans ill and kill fish, shellfish, manatees and dolphins.

Red tide is probably not caused by human action because it originates far offshore, but increased levels of nutrients in coastal ecosystems have been implicated in increasing the length and duration of red tides in Florida, Corcoran notes.

Nutrient pollution can fuel other HABs directly. Those HABs don’t always release toxic substances, but still cause significant damage. As the algae and organisms fueled by excess nutrients die, their decaying bodies consume large amounts of oxygen, creating zones where nothing else can live.

More than 400 so-called “dead zones” exist around the world. The dead zone in the Gulf of Mexico – an area where oxygen levels are so low that nothing can survive – is caused primarily by fertilizer that flows down the Mississippi River from the nation’s breadbasket states.

Low oxygen events regularly occur in Old Tampa Bay, often during or after blooms of the alga Pyrodinium bahamense, an organism that can live as a cyst for years, then spring into life when nutrient levels and temperatures increase. Blooms typically start during the warm summer months and are directly fueled by stormwater runoff, including lawn fertilizer and animal feces, according to University of South Florida researchers.

Across the state, in the pristine Indian River Lagoon, nearly 50,000 acres of seagrasses have been killed recently in a series of algal blooms that began in 2011. While the blooms – caused by an alga known as Aureoumbra lagunensis – is not toxic to humans, it can affect shellfish. It has also killed record numbers of manatees, dolphins and pelicans, but scientists are not clear about what caused those deaths because they all eat different food and the symptoms are not similar.

Back to the Future?

Prior to joining FWRI where she focuses on HABS, Corcoran had a totally different take on algae. She was working to design algal biofields in the deserts of New Mexico. Algae are the basis of most fossil fuel used in the world today, and may become the fuel of the future as well.

“Because algae don’t need arable land to grow, producing algal biofuel does not require that we stop growing food,” she notes. “The biggest challenge we’re facing is making algal biofuels cost-efficient.”

Their billion-years’ worth of experience in exploiting different nutrients and spectrums of sunlight may be the answer. “A lot of times, something happens and all the algae die because they’d been growing in a monoculture,” she said. “I was able to show that multiple algae living together created a much more stable ecosystem.”

Similar work, she adds, is now part of a four-year project led by Bradley Cardinale at the University of Michigan. His team is working to find the ideal combination of freshwater algae to become part of the next generation of biofuels.

Fast Facts:

- While seagrasses in Tampa Bay may be confused with marine macroalgae, or seaweed, they are very different species. Seagrasses actually evolved from land plants and have similar features including leaves, roots, flowers and seeds.

- Karenia brevis may be the “problem child” in Florida but it’s much less toxic than HABs found in in other parts of the world. Researchers are concerned that more toxic algae could invade Florida waters in ships’ ballast (see baysoundings.com/legacy-archives/winter2012/Stories/New-Rules-Invasive-Species-Ballast-Water.php).

- In China and Japan, where aquaculture is a significant economic engine, HABs are controlled with clay that adsorbs algae as it settles on the seafloor. That hasn’t been tried here because U.S. officials are concerned about potential harm to bottom-dwelling benthos.

- See more algae images at the Harmful Algae and Other Plankton Species gallery on the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission Research Flickr page.