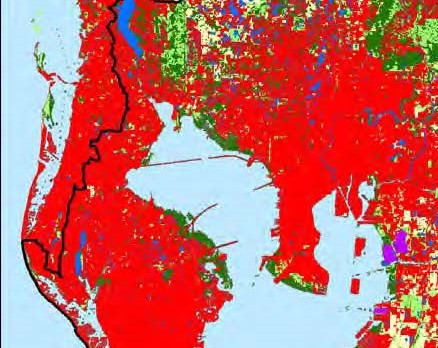

Old Tampa Bay – the bay segment north of the Gandy Bridge where tidal circulation is restricted – has long been considered “the problem child.”

Old Tampa Bay – the bay segment north of the Gandy Bridge where tidal circulation is restricted – has long been considered “the problem child.”

While seagrass acreage declined throughout southwest Florida, the most significant losses in Tampa Bay were in Old Tampa Bay. More than 4,041 acres were lost in Old Tampa Bay between 2018 and 2020 — a 38% drop. For the sixth consecutive year, Old Tampa Bay has failed to meet chlorophyll a targets, in part due to persistent blooms of a toxic dinoflagellate that block sunlight from reaching the bay bottom.

Old Tampa Bay’s watershed is surrounded by suburban neighborhoods in northwestern Hillsborough and central Pinellas County. It receives stormwater from a 160,000-acre watershed, including drainage from Lake Tarpon, which initially emptied into the Anclote River or the Gulf of Mexico before it was redirected for flood control in the 1960s.

As bay managers develop actionable plans to address the problems, consultants working with the Florida Department of Transportation (FDOT) are demonstrating that a bridge cut into the Courtney Campbell Causeway has improved water quality to the point where persistent seagrass beds can be expected to thrive in an area north of the project in Old Tampa Bay where they have historically been ephemeral.

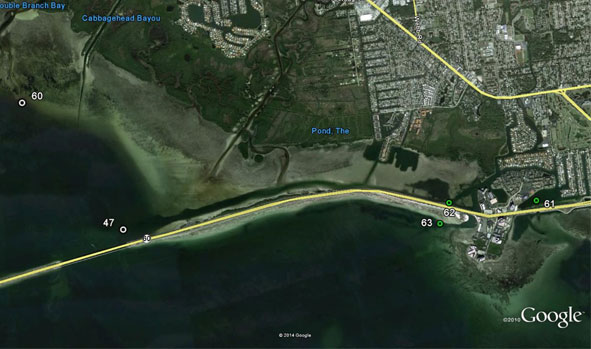

The 239-foot bridge cut in the causeway just west of the Ben T. Davis Beach improved tidal flow to the bay section north of the Courtney Campbell Causeway. “We finished two years’ worth of monitoring and we exceeded the targets – targets we thought were pretty aggressive,” said Shayne Paynter, water resources technical manager at Atkins.

Rather than track actual seagrass acreage, the monitoring effort focused on the chemical parameters that would enable the growth of seagrasses on approximately 300 acres near the eastern edge of the causeway. “Our focus was on improving water quality to the extent that it would allow seagrass to grow instead of tracking seagrass acreage that can be mercurial and ephemeral from season to season,” Paynter said.

Before the new bridge was built, scientists reported that seagrasses were more abundant the closer they were to the original bridge where tidal circulation improved, he said. “We also saw more shoal grass and widgeon grass north of the causeway – both less resilient species – than the turtle grass and manatee grass that dominate the area south of the causeway.”

Researchers also reported that chlorophyll a concentrations were 43% higher north of the causeway when compared to areas south of it, and total nitrogen concentrations were 23% higher in the northern sections before the bridge was built.

With the completion of the bridge in December 2018, the parameters had all met their targets, including tidal flux, salinity, chlorophyll a, and total nitrogen. “In fact, we modeled a 50% improvement, then all of the measured parameters improved by over 50%. Chlorophyll a, the key measurement in the health of bay waters, was reduced by over 82%,” Paynter said.

Bridge is a win-win for the environment, taxpayers and boaters

The new bridge was built following a new state law that encouraged FDOT to consider options besides traditional stormwater ponds to mitigate for water quality impacts from the project, which would have required “literally buying office buildings to build ponds,” said Dave Kramer, surface water regulation manager for the Southwest Florida Water Management District.

The new bridge was built following a new state law that encouraged FDOT to consider options besides traditional stormwater ponds to mitigate for water quality impacts from the project, which would have required “literally buying office buildings to build ponds,” said Dave Kramer, surface water regulation manager for the Southwest Florida Water Management District.

Paynter estimates that the bridge is as effective as 200 stormwater ponds in removing nitrogen, and internal FDOT cost analyses indicated that it was $100 million less expensive than building ponds that would achieve the same goal.

“It’s a win-win for everyone,” he said. “It improves water quality and ecological habitat far more than what we would have seen with much more expensive ponds, saves money for taxpayers both in construction costs and ongoing maintenance, and local residents, boaters, and water enthusiasts receive the direct benefit of cleaner, clearer water.”

Larger Impact Less Clear

While the new bridge has improved water quality in a 300-acre section, Old Tampa Bay has much larger problems that still need to be addressed, probably employing a range of actions. “There is no silver bullet – or one smoking gun – for Old Tampa Bay,” said Ed Sherwood, executive director of the Tampa Bay Estuary Program (TBEP).

Along with the potential for alterations to other causeways, researchers are looking at using oysters and clams to potentially filter the Pyrodinium quickly enough to stop blooms from persistently developing each summer – if the shellfish are abundant enough and able to handle the toxic substances created by the algae.

A recent workshop reviewed actionable management and research plans for bringing Old Tampa Bay into compliance with the Florida Department of Environmental Protection’s Reasonable Assurance (RA) determination for Tampa Bay. An updated RA Plan comes due in two years.

“We’re in limbo on the RA,” Sherwood said. “We missed some sampling opportunities last year because of the Covid shutdown, but we still have another year of testing to understand long-term water quality issues in Old Tampa Bay.”