When more than 15 inches of rain fell on the Tampa Bay region over a two-week period last summer, the entire three-county area was inundated. Roads flooded, creeks and ponds overflowed, and wastewater backed up into streets and was ultimately released into surface waters.

When more than 15 inches of rain fell on the Tampa Bay region over a two-week period last summer, the entire three-county area was inundated. Roads flooded, creeks and ponds overflowed, and wastewater backed up into streets and was ultimately released into surface waters.

The wastewater releases made headlines and angered citizens, but the images conjured of untreated sewage in Tampa Bay weren’t the whole story. The real issue was stormwater entering the wastewater treatment collection system and then overwhelming sewage treatment plants or overflowing from manholes.

The city of St. Petersburg Southwest plant, which also serves St. Pete Beach, Treasure Island and Gulfport, typically treats 20 million gallons per day (mgd) of sewage, but during the August rain event, was actually treating up to 40 mgd. Tampa’s Howard F. Curran Advanced Wastewater Treatment Facility, rated to treat 96 mgd, was successfully moving nearly 200 mgd through its system.

“You can’t tell me that just because it was raining that hard, residents across the region created that much extra domestic wastewater,” said Mary Yeargan, district director of the Florida Department of Environmental Protection and the person charged with ensuring compliance of environmental regulations.

The industry calls it the “I/I problem” — inflow and infiltration. In some cases, residents actually have tied their storm gutters into the sanitary sewer system, intentionally putting stormwater in the wastewater collection systems. “Of course, it’s not allowed — but it happens,” Yeargan said. “People don’t want water standing in their yard, so they connect to the sanitary sewer pipes to drain it off.”

Other times, people set up hoses to pump water from their streets, pools or backyards into manholes or wastewater cleanouts, where it becomes part of the wastewater system instead of simply running off with the rest of the stormwater. That, of course, makes it more likely that the manhole will back up and allow wastewater to escape into flooded streets.

Infiltration occurs when sewer pipes – particularly the old red clay or orangeburg pipe made of wood pulp and asphalt that no longer meet code – are below water level or the water table in heavy rains. The older pipe is more permeable, so stormwater can make its way into the sewer line and significantly increase the volume of water delivered to the wastewater treatment plant.

Some of that older pipe belongs to utilities – most of which have aggressive replacement programs — but many of the leaking pipes are the responsibility of individual homeowners. Replacing them with newer, less permeable pipe can cost thousands of dollars per household, but wastewater treatment demands can drop dramatically.

“People don’t understand the connection between wastewater and stormwater,” Yeargan said. “Anytime the water level rises in heavy rains, stormwater is going to infiltrate the sanitary sewer system, causing loads at nearby lift stations and the wastewater treatment plants to increase – sometimes to the point where the plant can no longer handle the increases.

“People don’t understand the connection between wastewater and stormwater,” Yeargan said. “Anytime the water level rises in heavy rains, stormwater is going to infiltrate the sanitary sewer system, causing loads at nearby lift stations and the wastewater treatment plants to increase – sometimes to the point where the plant can no longer handle the increases.

“There wasn’t a good choice, but releasing the untreated or partially treated wastewater may have actually prevented sewage from backing up into homes,” she adds.

Utilities look to the future

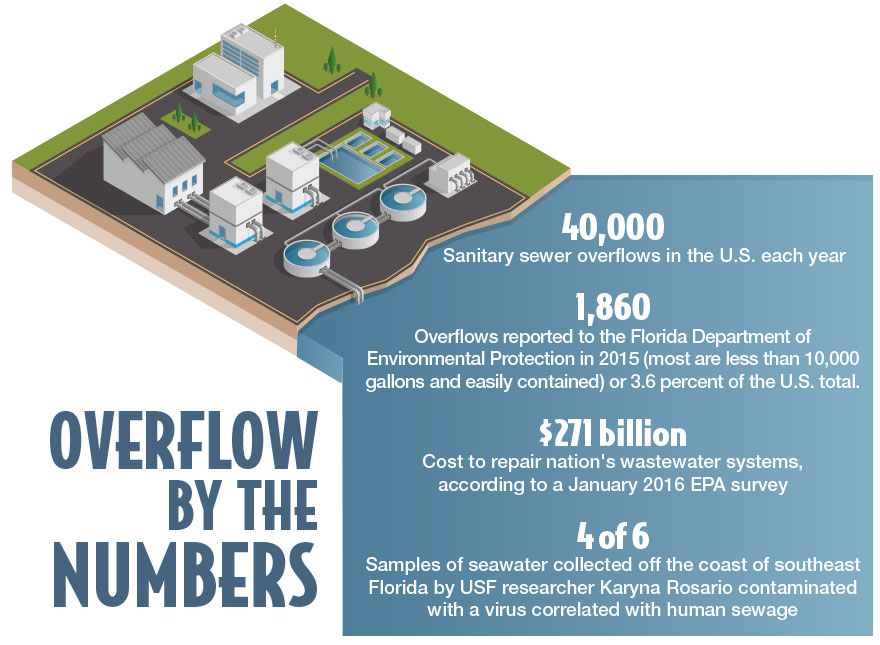

The Tampa Bay region is actually ahead of much of the state and nation in terms of collecting and treating wastewater, notes Jim Tully, a registered engineer and geologist who runs Florida Water Daily (www.floridawaterdaily.com) a website that tracks news about water and wastewater across the state.

“It would be difficult, if not impossible, to treat 100-year flows,” he said. “There are dozens of emergency discharges to surface waters in Florida every year – it’s normal even if it doesn’t make the news and it’s a national problem, not just something happening here.”

Recognizing that some wastewater pipes are more than 50 years old, most utilities already have replacement programs for their pipes in place. Funding is an issue, however. In much of the region, fees for treating wastewater are actually higher than the cost of water.

Technology is helping tackle the problem, Tully said. Flow testing blocks some pipes and then measures remaining water to see where inputs or infiltration may be occurring. In other situations, pipes are filled with smoke – where the smoke leaks out, water could leak in. Underground video cameras can find weak or broken piping.

Other technologies make it easier – and less expensive — to repair pipes than digging up streets and yards. “Sleeves” can be inserted into pipes, making them slightly smaller in diameter but much less permeable. In some cases, a spray sealer can be used. Some manholes in the region are so old that they are made of bricks; they can be made more impervious with “top hats” that drop in to resist infiltration.

And it’s not just heavy rainfall causing the problems over the long term, adds Maya Burke, senior environmental planner at the Tampa Bay Regional Planning Council. Sea level rise may also be increasing the potential for infiltration into the wastewater treatment systems.

FDEP also is setting up regular meetings of utility directors from across the region to share best practices in an informal setting, Yeargan said. “Most of them are pretty isolated (from each other) so this is an opportunity for round-table chats where they can talk about what happened and learn from each other.”

Funding remains an issue

Even as resident complaints about wastewater releases and flooding increased exponentially, not every local government has been willing to spend the money necessary to repair the long-standing problems. In Hillsborough County, stormwater fees increased from $12 to $30 for most homeowners in early 2015. The additional funding – more than $9 million per year – will help address an estimated $200 million backlog in stormwater projects and repairs. Pinellas County increased its stormwater fees in 2013 to raise an additional $18 million a year to spend on stormwater pipe maintenance and nutrient reduction. Pasco County also raised its stormwater fee to $57 per household this year, a $10 increase, although commissioners turned down a staff request to raise fees in the most-impacted watersheds after the heavy summer rains.

But the cities of Tampa and St. Petersburg have been less supportive of raising fees. In Tampa, the city council recently increased stormwater fees, but not enough to cover all improvements city staff had recommended. St. Petersburg is still considering its options, including borrowing money or using part of their proceeds from the BP oil settlement.

Funding is typically available from the state DEP, as part of a $4 billion revolving loan fund that offers local governments low-interest loans to repair or rebuild wastewater treatment facilities that are usually repaid from user fees. “We typically lend out $200 to $250 million per year, beginning with funding for feasibility studies and going through construction loans,” said Tim Banks, who manages the program.

“Over the past 30 years, regional partners have addressed many of the bay’s most pressing and visible challenges. Over the next 30 years, managers will have to tackle ‘wicked problems’ like non-point source pollution and climate change,” Burke notes. “Ensuring adequate resources are in place to protect Tampa Bay in light of these challenges is critical for both human health and the health of the bay which is directly tied to the region’s economy.”

By Vicki Parsons, originally published Winter 2016