Cameras whirred as Tonya Wiley directed the rescue of a seven-foot smalltooth sawfish from a pond off Bishop Harbor. However, saving that animal has been a long time coming for both the endangered species and the founder of Havenworth Coastal Conservation.

Like hundreds of today’s marine biologists, Wiley decided she wanted to work with sharks as a youngster, watching the 1975 film “Jaws.” After a circuitous route that took her through a stint in the Navy to earn GI Bill credits to be able to afford college, she drove from her native Texas to Sarasota in 2000 in hopes of getting a job at Mote Marine Laboratory working with blacktip sharks. That didn’t work out, but a couple of months later, she got a call from Colin Simpfendorfer at Mote asking her about a field position researching sawfish.

“I told him I didn’t know anything about sawfish – I didn’t even remember learning about them in any class,” Wiley recalls. “He said no one knows much about sawfish in the U.S. so they were starting this research from scratch. I loved that concept so I packed up and moved to Florida.

During her first year running Mote’s boat, they caught one sawfish. “And that was with me spending three weeks a month fishing,” she said.

By 2010, she’d moved back to Texas, returned to Florida, bought her own research boat and founded Havenworth Coastal Conservation. “I love being out on the water, and I love talking to people about sawfish and sharks.” Grants from the Tampa Bay Estuary Program, Save Our Seas Foundation, Disney Conservation Fund, Shark Conservation Fund, and the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission allowed her to research sawfish, sharks and rays, particularly their nurseries in Tampa Bay.

“We’re looking at the what, when and where newborn sharks are. We know they use the Manatee River, Terra Ceia Bay, and lower Tampa Bay as nurseries, but we needed to know more. For instance, we know bull sharks are born in the Manatee River around I-75, so when they started building a new bridge right through the middle of the nursery, we put a lot of equipment in the water and transmitters on sharks to see if it affected their habitat use.” The data are still being analyzed but it appears that there was minimal impact, she adds.

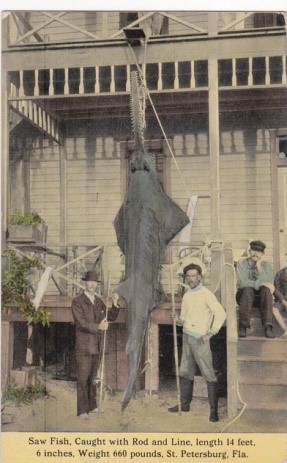

All along, she was watching for sawfish as their population appeared to be making a comeback and expanding their nursery area beyond the Ten Thousand Islands and Everglades National Park. With blade-like snouts studded with teeth on both sides (known scientifically as rostrums), sawfish could grow up to 16 feet long and made for an iconic catch for fishermen from Texas around to North Carolina.

Overfishing, combined with habitat loss, reduced their range to southwest Florida and the Keys. Things seemed to be improving for sawfish in 2021 when two juvenile sawfish were captured off Redington Beach, followed by the catch and release of three juveniles off Rattlesnake Key in 2023, and an adult male tagged off Longboat Key in 2024.

More recently, sawfish have been in the news for a mysterious spinning disease that killed at least 50 different fish species in the Florida Keys last winter after record-breaking heat the summer before. It’s still unclear what causes the fatal disease, but some experts believe it is an algal species that usually lives in coral reefs. Record heat allowed the algae to thrive on the seafloor, growing on dead corals, seaweeds and macroalgae. Fish low on the food chain inadvertently eat the toxic algae, and the toxins accumulate in predators, including sawfish

“We’re not sure what the long-term impact will be,” Wiley said. “We’ll be carefully watching populations, particularly newborns in Charlotte Harbor.” The losses in the Florida Keys make every fish even that much more valuable, particularly if climate change means that they are forced into habitats further north.

When Kane Mcree, a young fisherman participating in the Fire Charity Fishing Tournament, first caught the Bishop Harbor sawfish – and had pictures to verify it – Wiley rushed to the pond. “When I got there, I thought ‘how is there a sawfish in here?’ It’s completely isolated from Tampa Bay and it’s separated by a grated culvert to keep manatees out.”

She didn’t see the sawfish, but couldn’t discount the report. “So when we got another call from Kane saying he’d caught it again, we knew we needed to get it out of the pond before it got any bigger and the water got colder.”

She went back with a team on June 25, setting nets to capture it with no luck. On July 3, they returned again, this time with nets, kayaks, and rods and reels. “It’s a pretty good-sized pond so we were trying to find a needle in a haystack.”

Finally, on August 9, they returned with a drone, a bottom longline and fishermen in six kayaks.“We found it with the drone, moved all the gear to a back corner of the pond, as far from the road as you can possibly get, caught her on one of the longline hooks baited with ladyfish, then walked her across the road for release at the Bishop Harbor boat ramp.”

Wiley will be back at Bishop Harbor again soon, visually surveying the area, hoping to see the fish before she leaves Tampa Bay for the winter. Like the other six sawfish seen in Tampa Bay, she’s been tagged with an acoustic transmitter that will ping a vast system of receivers across the bay and its passes. “Nothing with a transmitter will get in or out of Tampa Bay without us knowing about it,” she quipped.

Data from the acoustic receivers is downloaded twice a year – in fall and spring. While the transmitters on the younger fish only lasted about 18 months and were detected around Rattlesnake Key for about a year, the bigger fish are wearing larger tags that last up to ten years. Judging by her size, the Bishop Harbor female is only about seven or eight years old, and won’t begin reproducing until she’s 11 or 12 feet long.

Being able to track her as she grows older will allow Wiley to follow her movements, habitat use, and migrations to see if she returns to Tampa Bay to give birth to her offspring, which could be in about four years. In the meantime, blood taken when she was captured may provide insights into the spinning disease that is killing so many adults in the Keys, and DNA samples will reveal her relation to the other sawfish tagged in Tampa Bay and throughout Florida.

“I’ve been working on sawfish for over 24 years now, and to finally see them in Tampa Bay was a very promising sign that the population was improving under the protections of ESA (Endangered Species Act). But that was before they started dying in alarming numbers in the Keys,” Wiley said.

Researchers are very concerned about the long-term viability of smalltooth sawfish and their ability to fend off extinction, particularly considering that the last largetooth sawfish was seen in the 1960s and is considered extinct, Wiley said. Even with protection under the ESA, they face multiple threats, including incidental catch in fishing gear (particularly mortality in shrimp trawls), the ongoing destruction of essential habitat, and the lethal spinning fish phenomenon in South Florida.

“The smalltooth sawfish population is in a seriously precarious state, making it vital to maximize the chance of survival for each and every sawfish – and I’m just so glad we got to put her in open water where she can go be a sawfish now.”

Learn more:

Sign up for Wiley’s monthly newsletter at https://lp.constantcontactpages.com/sl/eRXX8df

The Bishop Harbor sawfish was saved because Mccree knew to call for help. Wiley encourages all fishermen to report any sightings through www.SawfishRecovery.org, 1-844-4SAWFISH, sawfish@myfwc.com, and/or the FWC Reporter app.

To make a tax-deductible donation to sawfish research, visit https://oceanfdn.org/projects/friends-of-havenworth-coastal-conservation/

By Vicki Parsons, originally published Sept. 15, 2025