For most Tampa Bay residents, protecting our lakes, streams and bay from stormwater pollution means changing bad habits like over-fertilizing, blowing leaf and lawn litter into storm drains, or not scooping poop behind our pets. But some homeowners can take that commitment a step further and start capturing rain before it turns into stormwater, either with rain barrels or in rain gardens that thrive in wet spots.

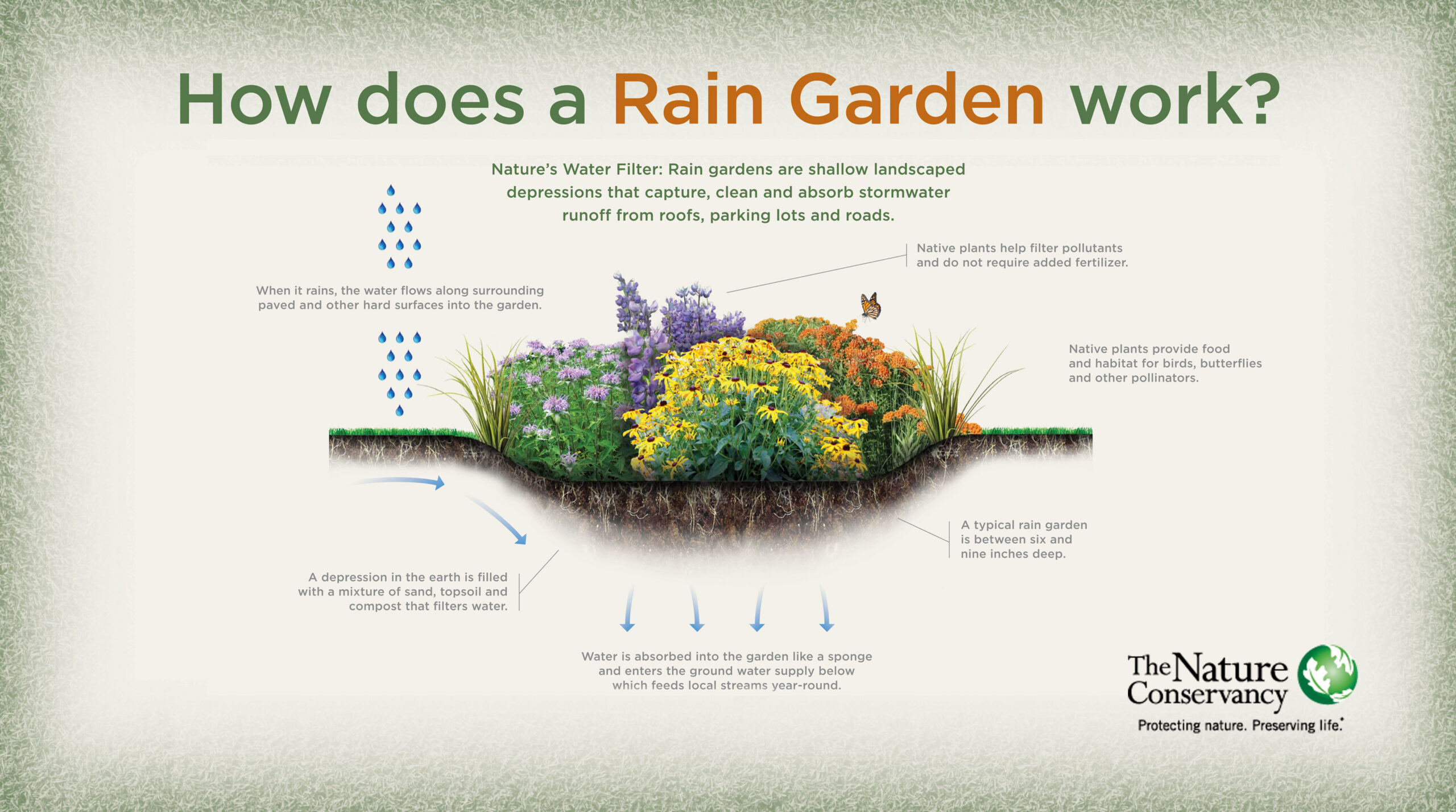

Stormwater is the largest single source of pollution in Tampa Bay. Rain that doesn’t absorb into the ground travels along paved surfaces into nearby storm drains before entering local waterways, picking up debris and other pollutants along the way. It carries nutrients that fuel the growth of algae, which block sunlight from reaching the bay bottom where seagrasses need it to survive. Stormwater can also fuel the growth of toxic algae like red tide or the Pyrodinium blooms that turn much of Old Tampa Bay rusty red nearly every summer.

Although most people don’t realize it, stormwater is seldom treated before it’s discharged into the nearest body of water, so it’s up to residents to capture what they can before it leaves our yards. One option is rain gardens that are low spots where rainwater has a chance to soak in before it washes away.

Ginny Stibolt, the author of many books on sustainable gardening in Florida including the Art of Maintaining a Native Landscape has planned and planted several rain gardens and has these tips:

The ideal size of a rain garden depends on how large an area will drain into it and how permeable the garden will be. Stibolt explains: “If you’re draining a 1000-square-foot roof, and the size of the rain garden is limited to 200 square feet, your rain garden should be five inches deep (1,000 divided by 200) to hold an inch of rain. But here in Florida, we can expect several inches of rain in a severe thunderstorm, so that rain garden should be designed to hold three or more inches of rain.”

If the soil is sandy, the rain will be absorbed more quickly. Also, plants with more leaves will soak up more water through transpiration than smaller plants or those with fewer leaves. For more capacity where there is no room to expand, rain gardens can be supplemented with dry wells.

“Plan the rain garden so that water soaks in, is absorbed by the rain garden plants, or can drain away in three days or less to keep the mosquitoes at bay,” she writes.

Sometimes, large rain garden projects are built around existing storm drains or swales. When this happens, dig out space for the rain garden so that most of the rain can collect below the level of the drain. This way, water will enter the storm drain only occasionally during severe storm events. If this project includes county or other municipal drain infrastructure, be sure to get the required permits before you start.

Designing a rain garden in Florida is challenging because plants need to tolerate both flooding and drought — some spots that are underwater during summer thunderstorms may be as dehydrated as a desert during a hot dry season.

Stibolt recommends choosing native plants to enhance the garden’s ability to support wildlife, particularly native bees and birds. Here’s her recommended list of rain garden plants with links to their Florida Native Plant Society plant profiles with more information, and to Stibolt’s articles on them if available:

Herbaceous Plants

Black-eyed Susan (Rudbeckia hirta)

Blue-eyed grass (Sisyrinchium angustifolium)

Climbing aster (Symphyotrichum carolinianum)

Dotted horsemint or spotted beebalm (Monarda punctata) Dotted Horsemint: An Appreciation

Fakahatchee grass or eastern gama grass (Tripsacum dactyloides)

Meadow beauty (Rhexia spp.)

Meadow garlic (Allium canadense) Chives and meadow garlic

Mistflower or blue mistflower (Conoclinium coelestinum)

Muhly grass (Muhlenbergia capillaris) An Appreciation of Muhly Grass

Netted Chain Fern (Woodwardia areolata) Netted chain ferns

Rain lily (Zephyranthes atamasca)

Starrush Whitetop or white-topped sedge (Rhynchospora colorata) White-Topped Sedge

Trees & shrubs

Arrowwood (Viburnum dentatum)

Bald cypress (Taxodium distichum)

Beautyberry (Callicarpa americana) For a more beautiful yard, plant more beautyberry

Cabbage palm (Sabal palmetto)

Dahoon holly (Ilex cassine) & inkberry (Ilex glabra)

Dwarf palmetto (Sabal minor) & Saw palmetto (Serenoa repens)

Elderberry (Sambucus nigra subsp. canadensis)

Wax myrtle (Morella cerifera) Wax myrtle: an under-used Florida native

Sweetbay magnolia (Magnolia virginiana)

Maples (Acer spp.) particularly the red maple (A. rubrum). Florida’s red maples.

Salt bush, Groundsel Tree, Sea Myrtle (Baccharis halimifolia)

Using native plants in Florida rain gardens doubles the benefits to our ecosystems by minimizing the impact of stormwater and providing critical habitat to wildlife. For the Stibolt’s full article on rain gardens, visit http://www.sky-bolt.com/garden/raingarden2.htm

By Vicki Parsons, originally published June 30, 2025