News reports earlier this summer predicted that Florida’s beaches would be overwhelmed by a stinky rotten mass of seaweed as a 5,000-mile floating bloom of sargassum macroalgae appeared to be headed to our shores. Luckily, the massive bloom dissipated for unknown reasons.

But tracking sargassum is critical to Florida’s tourism, and scientists at the USF College of Marine Science (CMS) will lead that effort with a five-year, $3.2-million grant from the NOAA Monitoring and Event Response for Harmful Algae Blooms program.

“The goal is to be able to put a single beach on alert when a sargassum inundation is imminent, instead of alerting the entire Caribbean,” said Brian Barnes, assistant research professor and physical oceanographer at CMS and the project’s principal investigator. “Up until this point, we have been using very coarse resolution satellite data to observe sargassum. This grant will help us look at sargassum at a finer spatial scale, and this capability will eventually allow the scientific community to provide real-time monitoring and forecasting.”

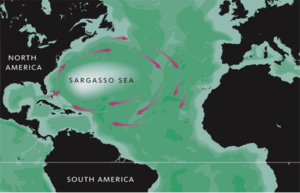

At sea, sargassum provides critical habitat for marine animals, including threatened loggerhead and hawksbill turtles, and serves as a nursery for a variety of fish. It forms in the Atlantic Ocean in an area known as the Sargasso Sea, which is bound by four circulating ocean currents. It’s typically present on Florida beaches during summer months where it provides vital nutrients as it decays.

But over the past decade, sargassum blooms have expanded and when the large masses wash ashore, the decomposing macroalgae can emit a mixture of dangerous gases, including hydrogen sulfide, that adversely affect the environment and human health. Cleaning up those mounds of rotten seaweed can cost millions of dollars.

The new monitoring system will allow researchers to observe smaller, but distinct patches of sargassum and give coastal resource managers more time to prepare for the inundation events. The team will also work directly with managers and other impacted groups to ensure that the new sargassum monitoring systems are accurate and advantageous.

Sargassum first became an issue in 2011 when researchers noticed a huge uptick in its abundance. This was shown to be partially caused by nutrient enrichment as detailed in a recent report co-authored by Chuanmin Hu, professor and director of the CMS Optical Oceanography Lab, who is also part of the sargassum-forecasting project team.

The abundance of sargassum has generally increased every year since, wreaking havoc on tourism industries and local economies when it washes ashore. By helping researchers better understand sargassum’s impact on water quality, NOAA’s funding may lead to more effective management plans.

“We want to know what happens to those areas that are subject to huge influxes of sargassum,” Barnes said. “This grant allows those areas most impacted by sargassum, such as Puerto Rico and the United States Virgin Islands, to better prepare for potential inundation events and, with appropriate intervention, lessen devastating effects to their communities.”