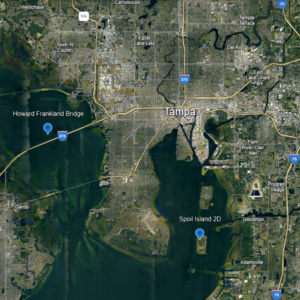

As giant cranes are building a new eight-lane span of the Howard Frankland bridge in Old Tampa Bay, an artificial island just east of the bridge in Hillsborough Bay is known globally as a significant bird nesting site.

Called 2D, it was originally built between 1978 and 1982 as a spoil island to store the soil and sand dredged from the bay bottom to create the shipping channel that accommodates the nearly 5,800 ships that traverse Tampa Bay every year. Surrounded by 29-foot containment dikes with a bowl-shaped interior where dredged materials can be pumped and stored, 2D is home to thousands of nesting birds including oystercatchers that are state-listed as a threatened species.

But like many of the coastal lands in Tampa Bay, ship wakes are severely eroding the western shoreline that’s adjacent to the shipping channel. Over the course of a year, these ship wakes generate roughly 100,000 joules per meter of cumulative wake energy, which is equivalent to the energy of a compact car traveling at 67 miles per hour slamming onto the shore. This destructive wave energy is washing away some of the critical habitats that beach-nesting birds depend upon, which is where the Howard Frankland construction comes in.

Once the new span is finished late next year, the original span – built in 1959 – will be demolished, leaving an estimated four million tons of concrete that will need to be disposed of. Port Tampa Bay has proposed barging 150-foot sections to build a series of breakwaters 500 feet off 2D that will minimize those damaging wakes on the island, creating calmer waters for seagrasses and a wider beach for nesting birds.

Questions still remain, including how the contractor hired to demolish the bridge will choose to dispose of the concrete as the price of recycled materials has risen significantly since the Covid pandemic, said Patrick Blair, vice president of engineering at Port Tampa Bay. “We’re hopeful that we’ll get those bridge sections for beneficial use,” he said.

“The Florida Department of Transportation (FDOT) encourages beneficial reuse,” adds Stephen Swingle, a consultant with Schneider Engineering who is working with the port. The Natural Resources/Environmental Impact Review Committee of the Tampa Bay Regional Planning Council’s Agency on Bay Management also supports the project, and will write a formal letter to FDOT asking that the material be provided for the port to enhance habitat.

“Fortifying the island against erosion has been a long-time, mostly losing, battle,” Blair said. Geotubes filled with dredged material are designed to hold the sand in place, but they didn’t work at 2D and the beach has been eroding for more than 35 years. But protecting the island’s dikes is critical to the port’s ability to maintain the 43-foot-deep channel that connects it to the mouth of Tampa Bay.

Every year, ongoing maintenance dredging generates over a million cubic yards of dredged material. The material that falls to the bottom of the shipping channel is too silty to use for beach renourishment and barging it to offshore sites would be very expensive. Other alternatives to protect the shoreline, like the WADS (wave-attenuating devices) used at the Alafia Banks Bird Sanctuary, “would get into the millions of dollars pretty quickly but we’ll need to look into other options if we don’t get the Howard Frankland concrete,” Blair said.

If the concrete can be used to protect 2D, Blair expects it to be the first phase of a longer-term habitat reconstruction that would take advantage of dredged material generated when the shipping channel is widened and deepened, estimated to begin in 2026. Unlike the silty material generated with maintenance dredging, material from the deepening projects is naturally occurring rock and sand, and will be suitable for further expanding the beach behind the protective breakwaters.