By Victoria Parsons – Bay Soundings 2004

The frog that goes jug-a-rum jug-a-rum in the night may be trying to tell you something.

The frog that goes jug-a-rum jug-a-rum in the night may be trying to tell you something.

In fact, trained listeners across the Tampa Bay region are learning to tell bullfrogs from cricket frogs so scientists can assess the health of local ecosystems.

“Frogs are very good indicators because they’re in tune with the water cycle and surrounding environments,” said Laura DeLise, director of the Hillsborough River Greenways Task Force, the organization that established the Frog Listening Network about five years ago. “They have very sensitive skin that’s also very permeable so high levels of pesticides and fertilizers impact them relatively quickly.”

While reports from around the nation indicate that up to 30% of frogs in some areas show deformities, that doesn’t appear to be happening in Tampa Bay, she adds. “The gopher frog, which lives in uplands that are being developed at a very fast pace, is designated as a species of special concern, but we don’t have any data to indicate that other frogs are near that point.”

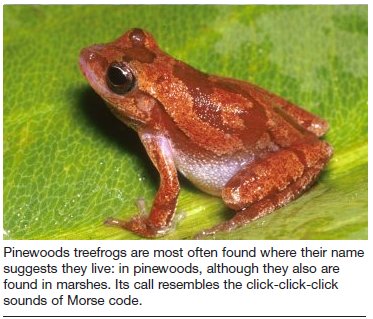

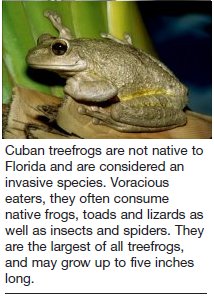

Nearly 30 species of frogs and toads are native to Florida, although most are tiny tree frogs that lay their eggs in ephemeral ponds – which kids probably recognize as mud puddles. After a good rain, when mud puddles are likely to appear, frogs start an intense sexual competition marked by calls with sounds that range from the bullfrog’s familiar jug-a-rum to noises that sound more like dogs, sheep and pigs or even fingers running across combs.

By identifying specific mating calls, the Frog Listening Network is helping to generate data that may be an early warning signal for other species in the region, she notes. Participants are asked to adopt an area like their backyard or a nearby park, listen to frog sounds for 30 minutes once a month and complete an easy on-line report.

By identifying specific mating calls, the Frog Listening Network is helping to generate data that may be an early warning signal for other species in the region, she notes. Participants are asked to adopt an area like their backyard or a nearby park, listen to frog sounds for 30 minutes once a month and complete an easy on-line report.

“Once a month is enough because once the frogs start calling you’ll hear just about everything that’s out there in 30 minutes,” she said. “We do ask that people monitor their ponds year-round because some frogs only call in the fall and winter.”

Most frogs have very specific habitat needs, but they typically stay close to wetlands that are less likely to be developed than uplands where the gopher frog lives. “Frogs typically don’t venture far from where they were hatched, and they usually go back to where they were hatched to mate if they possibly can,” she said.

Larger frogs typically need larger bodies of water for their tadpoles to survive. “It takes much longer for the larger frogs to metamorphose so they need more water and larger spots to hide,” she said. “Smaller frogs are fine in transient bodies of water, where their tadpoles are less likely to be eaten by fish.”

Even more than the data, however, the Frog Listening Network is an important educational initiative because it starts people thinking about habitat destruction and the damage caused by pesticides and high levels of fertilizers. “We train more than 1,000 people a year, but only about 10% regularly return data,” DeLise notes. “Our main purpose is education – we want to open people’s eyes to what’s happening in their back yard.”

Most people who take the training – including a 90-minute presentation and a packet of materials available for a donation – are amazed at how many frog calls they already recognize, she said. “They’ll say ‘I’ve heard that noise, it’s so nice to know what it is.’ Typically people pick up about 25 to 50% of the calls made by different Florida frogs in one session, then learn even more when they go out in the field and really listen.”

It’s a great program for kids too, because they typically have a good ear for the differences in frog calls. “A good ear is all you really need,” DeLise said.

It’s a great program for kids too, because they typically have a good ear for the differences in frog calls. “A good ear is all you really need,” DeLise said.

And summer is the best time to start listening for frogs because the rainy season brings on mating season for most species. “All the noises you hear on a night after a good thunderstorm are frogs looking for mates because their tadpoles have a better chance of survival after a rain.”

Good Frog, Bad Frog

Like bats, lizards and snakes, frogs don’t get credit for being the helpful neighbors most of them really are. They eat insects – including mosquitoes – plus they are critical components of the ecosystem. “They’re a source of food for a whole variety of animals, from fish that eat tadpoles to owls and hawks that eat larger frogs,” notes Mark Hostetler, an ecologist at the University of Florida.

And while many native toads excrete mild toxins, only the imported giant cane toad (Bufo marinus) is dangerous. Giant toads can grow to be more than nine inches long and weigh more than three pounds. Luckily for Tampa Bay residents, they’re sensitive to cold temperatures, so there are fewer cane toads here than in South Florida. Bufo toxins can be absorbed through skin but they’re most likely to harm dogs or cats. Toads are easily captured because they’re large and slow but they may be fatal, particularly to small dogs and cats. Along with profuse, frothy drooling, symptoms of toad poisoning include vigorous head shaking, pawing at the mouth, continuous attempts to vomit, lack of coordination and staggering.

If owners suspect a dog has caught a giant toad, they should immediately rinse the dog’s mouth — being careful to flush toxins out so they’re not swallowed — and call their vet.

Giant toads are most likely to be found near water bodies and typically don’t leave an aquatic environment except during summer rainy season. They’ll eat almost anything, so leaving pet food or water outside may attract them. Be sure it really is a giant toad, however, and not a southern toad.

Giant toads have large glands that angle downward behind their head to their shoulders and rough tan, dull green or black skin with many warts. The southern toad has smaller glands that are shaped like kidney beans and prominent knobs on its head that turn into crests that run down between its eyes. They are generally brown, black or red and have only one or two warts.

All photos courtesy of the Hillsborough River Greenways Task Force