Local Conservation Hero Retires from Audubon after 31 Years of Service

By Mary Kelley Hoppe

Bay Soundings 2004

Rich Paul retired in December after 31 years of service to the National Audubon Society, including two decades as guardian of Tampa Bay’s coastal island sanctuaries, which host some 50,000 pairs of nesting birds each spring. Bay Soundings pays tribute to this local conservation hero as he embarks on new adventures.

Rich Paul retired in December after 31 years of service to the National Audubon Society, including two decades as guardian of Tampa Bay’s coastal island sanctuaries, which host some 50,000 pairs of nesting birds each spring. Bay Soundings pays tribute to this local conservation hero as he embarks on new adventures.

Rich Paul is immersed, focused and devoted, a steady voice in a sometimes contentious sea of debate on matters concerning Tampa Bay, a statesman for the birds who has left an indelible mark while earning the respect and admiration of countless individuals.

“Rich is a consensus builder,” says Pinellas County Assistant Administrator Jake Stowers. “He doesn’t have to shout to be heard. He speaks with authority and people listen.”

That’s unlikely to change even after his retirement from the National Audubon Society after 31 years, including two decades advocating for protection of Tampa Bay’s bird colonies, among the most productive in Florida and the Southeastern U.S.

Long-time bay advocate Robin Lewis recalls one of Paul’s defining moments on the job. “It was 1989 and Rich had been documenting the number of seabirds nesting on 2D and 3D,” man-made spoil islands in Hillsborough Bay owned and operated by the Tampa Port Authority. The islands had inadvertently become important nesting grounds for birds crowded out of their native habitat by throngs of beachgoers.

Paul warned bay managers about the dangers of depositing new material on the islands during nesting season and lobbied for changes to keep the birds out of harm’s way. Ignoring warnings, the Army Corps of Engineers – later to become an ally in the effort – commenced dumping on the islands and flushed out out several nests, a tragic blunder that ultimately landed them on the front page of the Tampa Tribune.

State and federal wildlife agencies stepped in and halted the project until after nesting season.

Paul’s efforts and the Corps’ own remorse led to landmark policy changes in the early 1990s that made nesting birds a priority consideration in all future dredge material management plans in Florida. Today, Island 3D is one of the most important nesting sites in Florida for laughing gulls, black skimmers, Caspian terns and other ground-nesting species.

“Rich got religion and went up against the Corps,” said Lewis, who worked with Paul’s predecessors at Audubon. “It was a test under fire, and reflected well on his ability to pick up the torch and run with it.”

It also marked the beginning of a win-win partnership with the Corps and Port Authority that continues today, and the creation of a migratory bird protection committee co-chaired by the two agencies.

A decade earlier, Paul banded and monitored white-crowned pigeons in Florida Bay and the Bahamas, where intensive hunting threatened survival of the game birds. “They were taking them out at the worst possible time and place,” says Paul, describing how hunters picked them off, one by one, like sitting ducks during nesting season. Oris Russell, then Bahamian Minister of Agriculture, and Paul’s boss, Sandy Sprunt, “literally sketched out on a napkin in a bar the first bag limits in the Bahamas and set the first hunting season dates.” The hunting season was adjusted after Paul’s monitoring of breeding populations showed further changes were needed to protect the species.

Peers say his passion for birds is matched only by a passion for preserving the Audubon legacy. “Rich is probably one of the greatest historians we have,” says Walker Golder, deputy director of Audubon North Carolina. “He knows and cherishes Audubon history, he understands how this organization got started, and he’s great at making sure people carry that legacy into the field.”

“The thing that always struck me about Rich is no matter what Audubon is talking about, Rich is always focused on the birds and the habitat,” adds Norm Brunswig, Director of South Carolina Audubon. “He has always been the steady voice that said ‘don’t forget the resource, don’t lose sight of the primary mission, don’t forget what we’re here to do.’”

Brunswig likens Paul to a modern-day Guy Bradley, an embodiment of the American Audubon movement. Bradley was Audubon’s first warden, hired in 1902 to patrol the backwaters of the Everglades, protecting magnificent plume birds like the snowy egret from poachers who were once his friends. He was murdered three years later, presumably at the hands of hunters.

“One of the things that always amazed me about the Tampa Bay sanctuaries was the juxtaposition with so many people,” Brunswig says. “You look out from a bird colony and see Cargill (fertilizer company) or a bridge ferrying people across the bay. And there are as many birds nesting in Rich’s colonies as in the Everglades.”

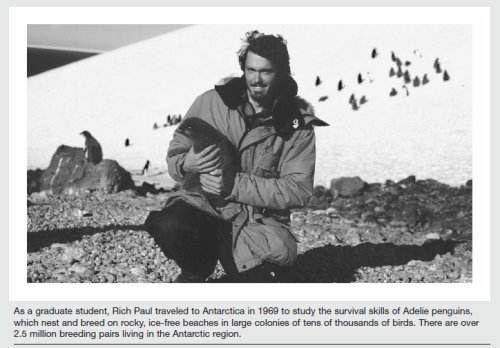

A graduate of Haverford College in Pennsylvania, Paul earned his master’s degree in wildlife ecology from Utah State University. A chance meeting with a professor there led to a four-month expedition to Antarctica in 1969 to study the survival skills of Adelie penguins. Paul recalls “a world of black and white, with very little ground between life and death.

“We devised models of predators — mostly leopard seals and skuas (gull-like birds) — then rigged up portable lines over the nesting penguins to document ‘fight or flight’ responses,” says Paul. “Mostly the penguins slept through it. We learned what bad research was.”

Fast forward to 1994, when Paul was named Wildlife Conservationist of the Year by the Florida Wildlife Federation; a year later he received the Golden Egret Award, Audubon’s highest career service award. In 2001, the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation honored him with the Chuck Yeager Award for action and achievement.

When Paul arrived in Tampa Bay in 1980, there were 10 islands and three active bird colonies under Audubon watch. Today, there are 50 colonies and 50,000 breeding pairs in the coastal sanctuaries, which stretch from Tarpon Springs to Midnight Pass in Sarasota.

Full circle

These days you’re likely to find the tall, lanky wildlife biologist out in the field, among the birds, where we found him on a recent sun-drenched Saturday in April – keeping tabs on a flock of American oystercatchers on a spoil island in Tampa Bay, as the Corps of Engineers waits in the wings to resume work at the close of another bird nesting season.

“Here’s a bird literally living on the edge, on beach nesting habitat only a few dozen yards wide, which happens to be the most popular habitat around,” he says. “Watching them struggle to successfully raise a baby oystercatcher, against all odds – in an area with 125,000 registered boats and three million people – is hugely exciting, hugely suspenseful.”

Rich on Reds

Among the world’s foremost authority on reddish egrets, Rich Paul’s love of reds was fueled in the 1970s with an intensive, six-year study of the rare crimson-hued bird in Texas and Florida. Reddish egrets were all but eliminated from Florida in the late 1800s, hunted for their exquisite plumes which were sold to milliners to adorn ladies’ hats. The species rallied in the 1940s but didn’t come back to Tampa Bay until the mid 1970s. Paul documented the first colony of reds at the Alafia Banks. Today, there are 50 to 60 breeding pairs in Tampa Bay.

As part of the study for the National Audubon Society, Paul examined some 200 historical specimens, while reviewing original literature on the birds at some of America’s finest libraries and museums. “I was handling specimens that were 142 years old, including some collected by John James Audubon himself. It was a pure thrill to see these birds.”

Rich Trivia

“Friends of Rich” who think they know this birding luminary well may be in for a few surprises. Test your Rich IQ with this short quiz.

1. As a graduate student at Utah State University, Rich studied:

a) The rise and fall of bald and golden eagles

b) The social behavior of Uinta ground squirrels

c) Courtship rituals of the elusive mangrove cuckoo.

2. Which of the following birding luminaries shares a birthday with Rich Paul?

a) W.E.D. Scott

b) Roger Tory Peterson

c) John James Audubon

Answers:

1 (b), 2 (c) – John James Audubon and Rich Paul were born 161 years apart on April 26.