From cattle to caviar: Things aren’t what they used to be down on the Florida farm.

On a 200-acre ranch not far from the asphalt ribbon of I-75 in Sarasota, Mote Marine Laboratory is preparing to harvest crops of caviar from farm-bred sturgeon. Banking on a steady stream of technological advances, Mote hopes to show that aquaculture can move inland and the U.S. can finally become a player in worldwide seafood production.

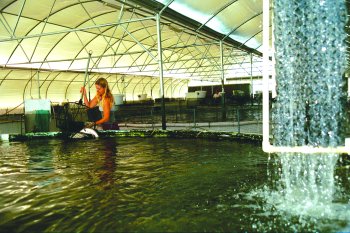

The venerable marine research facility is plowing big bucks into its new aquaculture park in eastern Sarasota County, where it is designing and testing technology to make aquaculture more affordable and environmentally sustainable. Cost-effective water recycling technology is the lynchpin; it would eliminate the need for aquaculture outfits to operate on the coast where land is costly and environmental impacts are greater.

So far, Mote has poured more than $3 million into the research park, which includes freshwater grow-out facilities for Siberian sturgeon, a sturgeon hatchery, grow-out facilities for saltwater species including snook, a marine hatchery and nursery, and research and development units.

A commercial sturgeon processing plant is under construction. Workers will eventually pluck caviar eggs from reproductive female fish, and ready the pricy delicacy and sturgeon meat for market.

Siberian sturgeon are excellent candidates for culturing in land-based recirculating systems, according to Dr. Kevan Main, director of Mote’s Center for Aquaculture Research and Development. “They’re really hardy fish – easily adapted to recirculating tanks,” as opposed to fish that require a pond or lake.

While the same technology could be used to farm native sturgeon for stock enhancement, culturing native sturgeon is illegal in Florida. The prohibition stems from concerns that hatchery-bred sturgeon might genetically taint wild stocks.

Mote’s foray into commercial sturgeon production supports the park’s overall research mission, Main says. “We have two major focuses. One is the production of snook and other animals for stock enhancement. In that arena, we’re developing culture methods as similar to nature as possible.”

The other major focus is on the design of water filtration and recycling systems that will make it cost effective for aquaculture to move inland and result in fewer environmental impacts.”

Sturgeon is the pelagic cash cow that’s expected to make it all possible. “Once that project is generating revenue,” says Main, “the end goal is to have an income stream that will support the 200-acre operation, but we’re many years from that.”

At build-out, the facility should support 200 metric tons of sturgeon. Of that about 88 metric tons will be harvested annually for food, yielding another 4.5 metric tons of caviar.

Mote is also receiving state funding to develop technology that would help Florida farmers grow high-value marine fish like pompano. The facility will be engaged in everything from producing eggs and larval techniques to grow-out of fish and production of pompano brood stocks.

Taming the trade deficit

After oil, seafood imports are the second highest contributor to the national trade deficit.

In fact, the U.S. produces less than one-third of the $10 billion worth of seafood it consumes each year.

Commercial and recreational fishing already capture the maximum they can from the sea, and many fisheries are severely exploited or depleted. And worldwide demand is growing. Over the next 12 years, annual seafood demand is expected to almost double to an estimated 60 million metric tons of fish a year.

Simply put, if we want to eat fish, we have to farm fish.

That presents its own challenges. Around the world, aquaculture farms are traditionally located on coasts. They take in sea water and discharge wastewater back into the ocean.

Recycling technology can change that and free up operations to move inland where land is cheaper and more abundant. But the technology and process of fish domestication is still relatively new.

Bringing up baby

Currently, Mote purchases fertilized sturgeon eggs from farms in Europe, hatching them on-site in tanks chilled to 50 to 60 degrees Fahrenheit. Eventually, the research park will produce its own brood stock.

Currently, Mote purchases fertilized sturgeon eggs from farms in Europe, hatching them on-site in tanks chilled to 50 to 60 degrees Fahrenheit. Eventually, the research park will produce its own brood stock.

The sturgeon are grown out in 25-foot diameter indoor tanks each six feet deep. Over the course of several months, the fish are gradually acclimated to ambient temperatures.

Males are harvested at two to three years of age at an average of 12 to 20 pounds. Females reach reproductive age after five to eight years, when they are harvested for caviar and meat. Adult sturgeon can grow anywhere from 50 to 100 pounds.

Filtering Finesse

Using gravity, process water from the facility is scrubbed of solids in a series of tanks filled with plastic media resembling pasta wheels. After removing ammonia and nitrates, ultraviolet lights are used to sterilize the water before it is fed back into the fish tanks.

For freshwater processing, Mote’s goal is to recycle up to 90 percent of its fish water; for marine fish, 90 to 95 percent.

For freshwater processing, Mote’s goal is to recycle up to 90 percent of its fish water; for marine fish, 90 to 95 percent.

Florida farmers can come here to see what we’re doing and take it to the next step, says Main.

“The majority of marine fishes now are either imported from third-world countries or caught from a dwindling commercial fishery,” she says.

“We have to get away from the hunter-gatherer mentality. I want the U.S. to be a player in producing the seafood we eat.”