While sports fans eagerly await results from the Super Bowl, the Stanley Cup or the World Series, the results of the 2022 seagrass survey are even more important to bay managers.

While sports fans eagerly await results from the Super Bowl, the Stanley Cup or the World Series, the results of the 2022 seagrass survey are even more important to bay managers.

With good winter weather, 90% of the images covering the 80,000 acres of seagrass habitat from Tampa Bay to Charlotte Harbor were captured by mid-January, said Chris Anastasiou, chief scientist and seagrass mapping program lead for the Southwest Florida Water Management District. And with environmentalists across the region focused on the loss of seagrasses in Tampa Bay between 2018 and 2020, the water management district is setting an aggressive schedule to release the 2022 data.

“We would typically target a release date for the 2022 maps in March 2023, but this year we’re pushing to complete draft maps for Tampa Bay in the summer of 2022,” Anastasiou said.

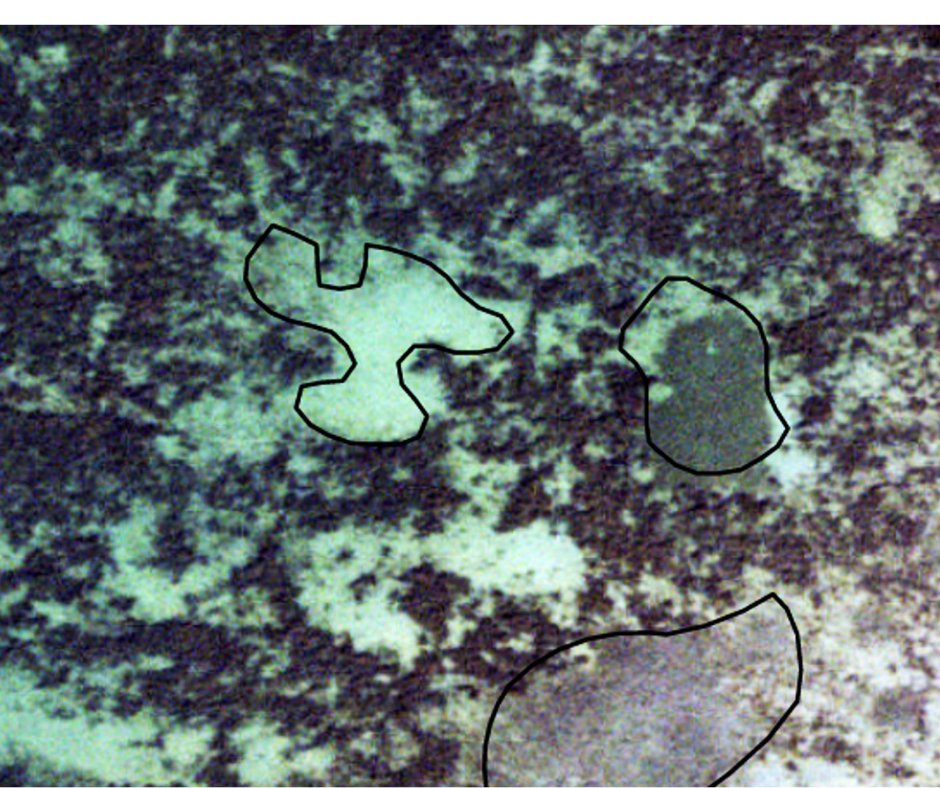

![]() Not only will the new maps be completed earlier, but they’ll also be significantly better. Seagrass habitat maps are created using specially collected aerial imagery. Previous maps used digital imagery with one Pixel Per Foot (PPF) resolution. In other words, each pixel or dot on the screen represents one square foot of bay bottom. This year, the imagery will have six-inch pixel resolution for a much clearer picture.

Not only will the new maps be completed earlier, but they’ll also be significantly better. Seagrass habitat maps are created using specially collected aerial imagery. Previous maps used digital imagery with one Pixel Per Foot (PPF) resolution. In other words, each pixel or dot on the screen represents one square foot of bay bottom. This year, the imagery will have six-inch pixel resolution for a much clearer picture.

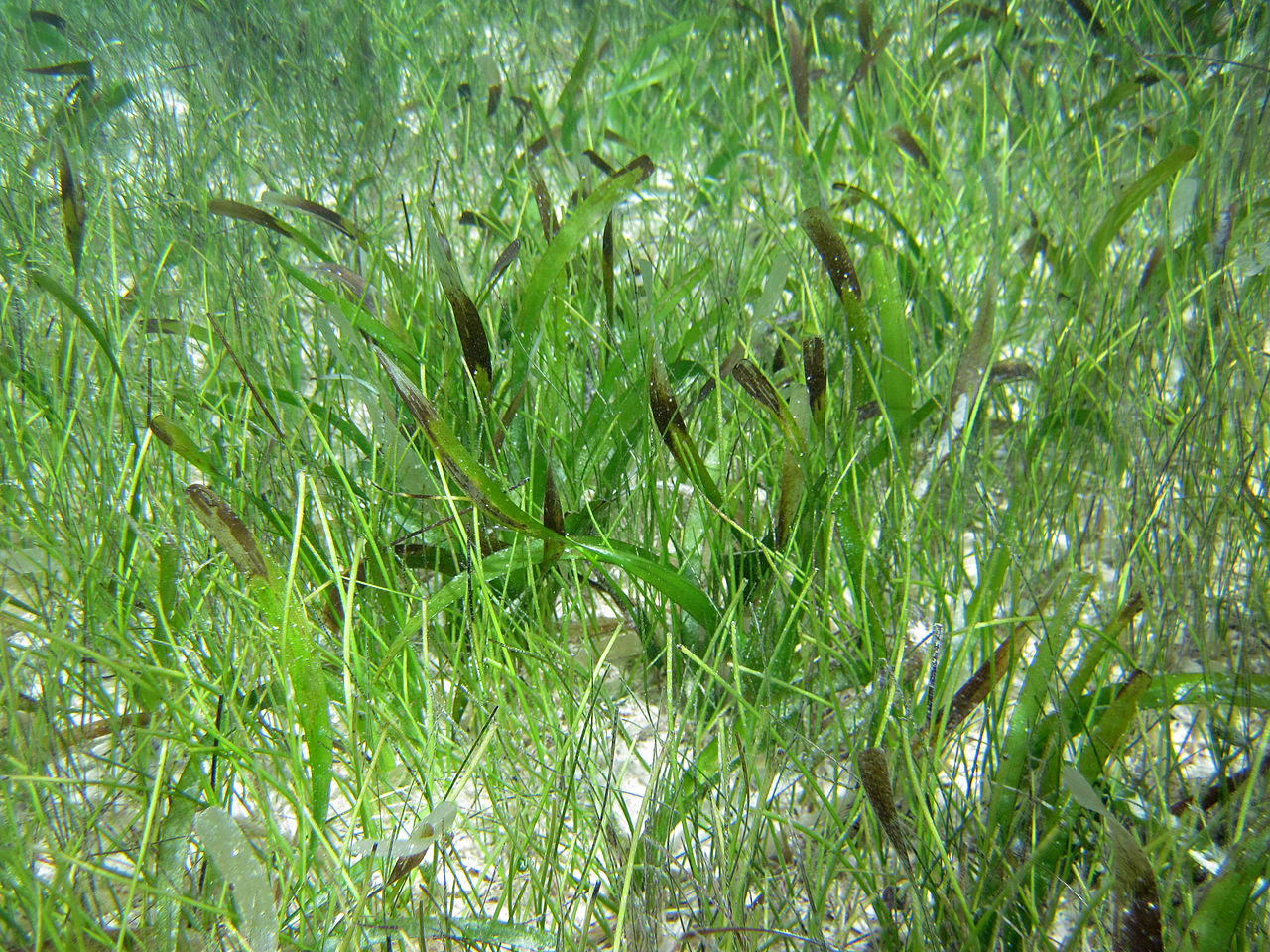

Underwater field verification also is benefitting from new technology. “We used to put a snorkeler in the water who would swim around and report their observations to personnel on a boat working frantically to write everything down on a clipboard,” Anastasiou said. “Now the use of high-definition video cameras and remotely operated vehicles (ROV) are making field verification much more efficient while providing some striking videos of the habitat.”

Seagrasses are critical habitat

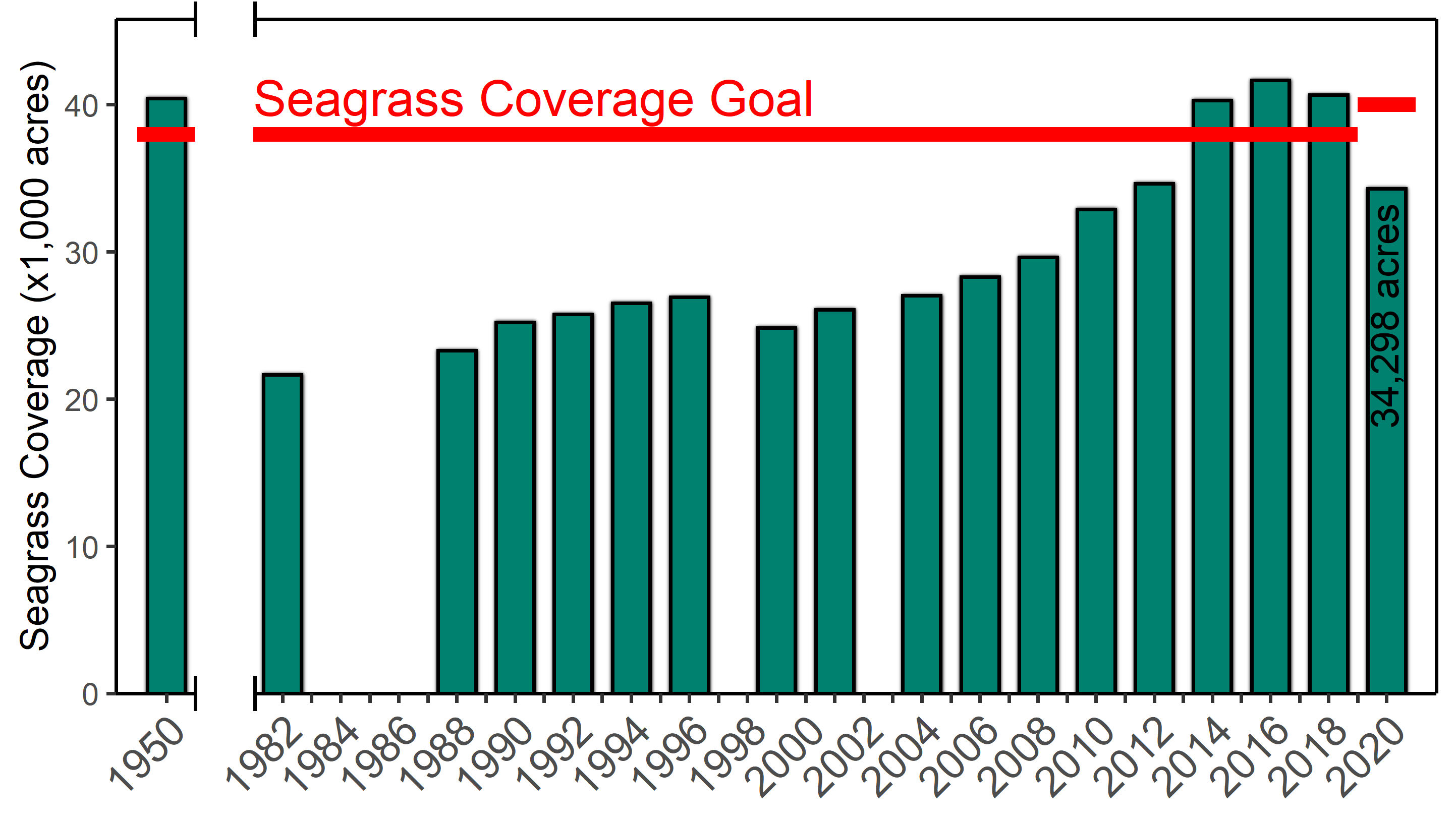

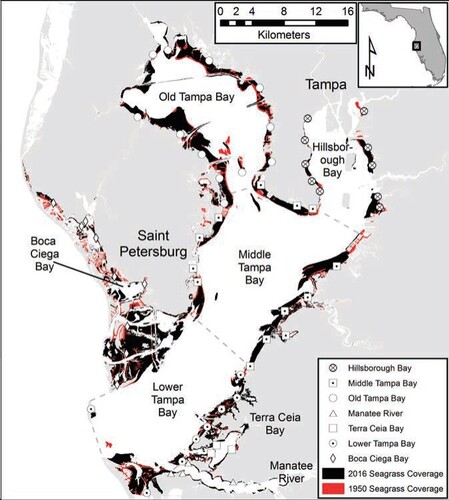

Along with providing food and shelter for many important species, seagrasses are important indicators of the bay’s overall health because they are sensitive to changes in water clarity and quality. Seagrass acreage rebounded dramatically over the past 40 years, surpassing the ambitious goal of 38,000 acres originally set in the 1990s. However, more recent surveys in 2018 and 2020 revealed significant seagrass loss in Tampa Bay, Sarasota Bay and Charlotte Harbor. In Tampa Bay, Old Tampa Bay and Hillsborough Bay saw the greatest seagrass losses of 38% and 43%, respectively.

Stormwater runoff, which carries fertilizers, pesticides, petroleum byproducts and animal wastes into the bay, is the largest source of the pollution which has been historically linked to seagrass losses in Tampa Bay. However, recent losses in places like Old Tampa Bay have occurred at a time when pollutant loads continue to decline.

“The research community, including the Tampa Bay Estuary Program and its partners, are working hard to understand the causes of this recent decline,” Anastasiou. “We’ve seen a significant increase in rainfall over the past 10 years or so when compared to historic averages and that could be having an impact.”

Photo courtesy Darian Photography

Climate change also may be playing a role, particularly in Old Tampa Bay where a toxic algae called Pyrodinium bahamense blooms every year in such abundance that the water turns rusty red and blocks the sunlight that seagrasses need to survive. The algae thrives in warmer water so the blooms may be getting longer and stronger as temperatures increase.

Seagrasses vs. Attached Algae

Along with seagrass losses in Old Tampa Bay, scientists are carefully tracking the growth of Caulerpa, an attached macroalgae that has replaced seagrasses in many areas of the bay. Seagrasses are plants that evolved on land and then returned to the sea; Caulerpa is a large green algae that attaches to bay bottom with “holdfasts” that are much less resilient than seagrass roots.

“Seagrasses derive most of their nutrients from the sediments via their root-like rhizomes,” Anastasiou said. “Attached algae like Caulerpa feed on nutrients in the water column, so when you have an excess of nutrients in the water column you tend to have more attached algae.”

The long-term implications of Caulerpa are still unknown, he adds. “They are more ephemeral than seagrasses because they don’t have roots, but they do function as habitat and they’re better than bare sediment.”

Caulerpa have less nutritional value, however, and are a key reason why record numbers of manatees are dying in the Indian River Lagoon, where nearly 60% of the seagrasses have been replaced by Caulerpa. “That’s not likely to be an issue in Tampa Bay where tidal waters flush most of the bay more often than in the Indian River Lagoon,” he adds.

The 2022 Tampa Bay survey will clearly distinguish seagrasses from Caulerpa so that scientists can determine how extensive they have become, particularly in Hillsborough and Old Tampa bays.