Established in 1985, its members include representatives from recreational and commercial fisheries, industrial, regulatory, academic and scientific sectors, local, regional, state and federal governments, and legislators. It serves as a broad-based forum for open discussion of the myriad issues involving the estuary, and as a voice for protection, restoration and wise use of the bay by the entire region.

Its meetings, held on the second Thursdays of most months, are open to the public. Learn more at http://www.tbrpc.org/abm/abm_agendas.shtml or email maya@TBRPC.org to be notified when agendas are finalized.

[su_divider top=”no”]

Bay Waters Reflect Great Progress

By Tom Ash, Assistant director/water management division

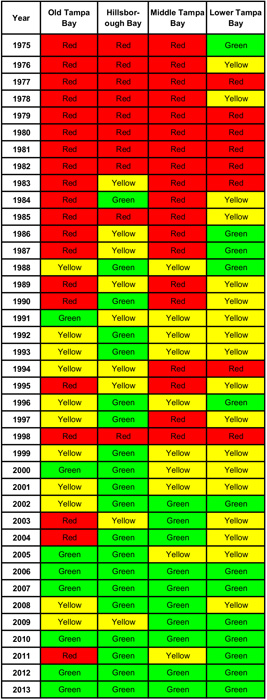

The Environmental Protection Commission of Hillsborough County monitors over 260 water quality stations throughout Tampa Bay and its tributaries. The vast majority of these stations have been monitored monthly for over 40 years. Of the dozens of various water quality parameters that are analyzed each month, none are as simple to perform – or as important to the average citizen – as water clarity.

Clear water is the one goal that gets us to every other goal. It is the key to our amazing success story with seagrass recovery. It tells us whether microscopic algae blooms, measured via the photosynthetic pigment chlorophyll-a, are under control. This, in turn, is an indicator of how successful we are in managing nutrient inputs into the bay — which, in turn, is a reflection of how a community can tackle problems together and form public and private partnerships that make hard choices based on science and a common goal of protecting our most valued natural resource, Tampa Bay.

We have experienced outstanding water clarity in much of the bay over the last couple of years. Fishermen know this. Boaters know this. Kayakers know this. Anyone who enjoys spending time on the water has noticed this and they are happy to share their stories with anyone who is willing to listen. Our own scientists at EPC – the very people who day-in and day-out traverse the bay to collect this data and their colleagues in Pinellas and Manatee – are all talking about how great the bay looks.

Let me give you some idea of what a big deal this is. If you draw a straight line from the Little Manatee River to roughly the St. Pete Pier, everything south of that line would comprise most of Middle Tampa Bay and all of Lower Tampa Bay. EPC has 17 evenly distributed water quality monitoring stations within that segment. In 2013, at times, every single one of those stations had what we call “visible bottom” all on the same day. That is to say that you could see the bottom of the bay from the boat in water that, in several places, was more than 30 feet deep!

This is an incredible achievement for a bay that, just 20 years ago, was struggling to meet many of our water quality management goals. We have certainly come a long way. While there is still work to be done and we must remain ever vigilant, let’s take a moment every once in a while to look into the water and reflect on the progress that has been made.

[su_divider top=”no”]Tampa Bay Estuary Program Celebrates “Green Lights”

By Nanette O’Hara, public outreach coordinator

The Tampa Bay Estuary Program capped off a successful 2013 with a second consecutive year in which all the major bay segments met water quality goals. In fact, scientists collecting water quality data in the bay reported exceptional visibility in many areas, despite a very rainy summer followed by a wetter-than-normal winter.

TBEP continued to work with its local government partners, key industries and regulatory agencies to ensure that levels of nitrogen – the bay’s primary pollutant — are reduced over time, to provide “reasonable assurance” that water quality targets can be met, and seagrasses can continue to expand.

We also continued a comprehensive, multi-faceted research initiative in Old Tampa Bay to address ongoing concerns over water quality and seagrass growth in this large bay segment bisected by three major bridges. Among the research and restoration efforts in this area:

- Development of an integrated computer model incorporating circulation, nutrient inputs, and other factors, analyzing how various management options affect those elements. This model will allow bay managers to assess which restoration activities could provide the most cost-effective environmental benefits.

- Ongoing restoration and enhancement of tidal wetlands in the Feather Sound area to naturally cleanse stormwater runoff, improve water quality, restore natural hydrology, enhance habitat value and facilitate seagrass recovery. Volunteers were enlisted to help remove invasive species and install native plants as well.

- Initiation of an innovative project to completely or partially remove a concrete weir on Channel 5, a channelized bay tributary in Pinellas County, to improve water flow and provide habitat for snook and other fish.

Other important accomplishments for TBEP during 2013 include:

- The launch of a long-term monitoring plan to track over time the impact of climate change on critical coastal habitats such as mangroves, salt marshes, salt barrens, freshwater wetlands and coastal uplands in the bay watershed.

- Establishment of restoration targets for freshwater wetlands that seek to restore the historic balance of these important but significantly impacted habitats, including cypress swamps and grassy marshes.

- Creation of a traveling exhibit of photos taken locally and around the world that illustrate the impact of extreme high, or “king tides,” on shorelines and structures. The traveling exhibit, displayed at libraries, museums, and education centers throughout the bay’s watershed, visually depicts how rising seas might affect natural resources and community infrastructure.

- Provided ongoing support for local fertilizer ordinances through a “Be Floridian” campaign that uses social media, digital ads and community outreach to encourage residents of Tampa, Manatee and Pinellas to “skip the fertilizer” during summer months and protect the waterways that are our major source of fun.

MacDill Restorations Win National Award

before it enters Tampa Bay.

Ongoing restorations at MacDill Air Force Base, including a 111-acre project completed last year (see Bay Soundings, Fall 2013), have been recognized by the National Military Fish & Wildlife Association at a joint conference with Wildlife Management Institute/North American Wildlife and Natural Resources.

The project was completed in a partnership between Southwest Florida Water Management District’s SWIM (Surface Water Improvement and Management) program and the U.S. Air Force. With more than seven miles of shoreline, including a golf course and surrounding mangrove forests at the southern tip of the densely populated Interbay Peninsula, MacDill is home to 16 listed species including two bald eagle nests.

Ongoing initiatives at the base include restoration of mangrove forests by flattening mounds created when mosquito ditches were dug decades ago. Rather than moving heavy equipment through sensitive habitat, hydroblasts will knock down the mounds with minimum impact.

A second project planned for later this year will fill in low areas near the airfields to make them less attractive to birds – which can collide with planes and cause significant damage. To mitigate for those wetland losses, an old spoil area will be excavated and replanted with marsh grass.

[su_divider]

SWIM Restorations Make a Difference in Tampa Bay

Over the last two decades, the Southwest Florida Water Management District’s SWIM (Surface Water Improvement & Management) program, in partnership with local governments, has completed more than 75 water quality improvement projects providing treatment for nearly 69,000 acres of Tampa Bay’s watershed.

In addition to its restoration and water quality improvement projects, SWIM held events to install 31,600 marsh plugs at three coastal restoration sites, including the commemorative installation of the one millionth marsh grass plug harvested from the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission’s marsh grow-out pond, originally funded by SWIM.

SWIM also was recognized with four awards in the 2013 Tampa Bay Regional Planning Council’s Future of the Region program including first place for the Clam Bayou Ecosystem Restoration and Stormwater Treatment Project; (see Bay Soundings, Summer 2011), second place for the South Bayshore Water Quality Improvement Project, honorable mention for the Bayhead Stormwater Harvesting Park Project and the first place award in the cultural/sports/recreation category for the Bradenton Riverwalk Park.

[su_divider]Slowed Population Growth Limits Need for New Water Sources

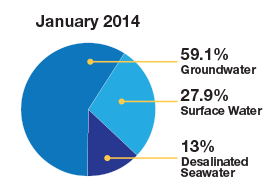

Fifteen years ago, two million people in the Tampa Bay region depended upon the Floridan aquifer for their drinking water. “Water wars” had broken out as governments fought over drinking water for growing populations and landowners pointed out shrinking lakes, vanishing wetlands, dried-up wells, and a surplus of sinkholes.

The creation of Tampa Bay Water in 1998 consolidated drilling permits and moved the region forward to alternative uses, including a desal plant and a 15-billion-gallon reservoir as well as an increased focus on conservation. A long-term master plan for water supply now being completed does not call for additional construction over the next five years and nearly 40% of potable water now comes from sources other than the aquifer.

[su_divider]Tampa Bay Nitrogen Management Consortium – A Partnership for Progress

By Ed Sherwood, Tampa Bay Estuary Program

The Tampa Bay estuary is probably the world’s most recognized success story in terms of ecosystem recovery even as the population within its watershed continues to grow. Part of this success is due to the collective efforts of a public-private partnership forged in the mid-1990s by government and business leaders in Tampa Bay.

The Tampa Bay Nitrogen Management Consortium (NMC), an alliance of local governments, agencies and key industries bordering the bay, has invested more than $430 million since the 1990s to help clean up the bay. Their investment has reduced nitrogen in Tampa Bay to 400 tons per year. Nitrogen is the bay’s prime pollutant of concern because it can fuel algae blooms that cloud the bay’s water and prevent underwater seagrasses from growing.

has reduced nitrogen loading to the bay by 400 tons per year.

The NMC is a unique model for ecosystem restoration partnerships. Early on, the group decided to share responsibility to help clean up Tampa Bay. Members voluntarily developed nitrogen load reduction targets for the major bay segments to help promote seagrass recovery. Their efforts, combined with state regulations to improve wastewater treatment plants, have cut nitrogen loads to Tampa Bay by half since the 1970s.

Rob Brown, NMC government co-chair and environmental protection manager for Manatee County’s Natural Resources Department sums it up well: “The Tampa Bay partners realized that we needed to include the bay area industries, agribusinesses and other stakeholders if we wanted to reach our nitrogen reduction goals. The local governments could not do it alone.”

The NMC is now focused on maintaining the bay’s health through a formal agreement limiting the amount of nitrogen that individual communities or industries are permitted to discharge. These individual allocations were first developed proactively by NMC participants in 2009 and “reasonable assurance” that the limits are being met must be provided to state and federal regulators every five years.

The NMC is one of the few public-private partnerships in the nation to routinely report its progress in meeting community restoration goals for a waterway. The next update is scheduled for 2017 – about the time the bay is expected to reach the critically important goal of restoring or protecting 38,000 acres of seagrass in Tampa Bay.

[su_divider]Audubon’s Coastal Islands Sanctuaries Celebrates 80th Anniversary

This Spring, Florida Coastal Islands Sanctuaries (FCIS) celebrates its 80th anniversary. It all began in 1933 when Dr. Herbert R. Mills traveled from Tampa to a bird colony “in the wilderness of Hillsborough Bay” and found that nesting herons and ibis on Green Key had been shot and chicks were dying in their nests. A member of the Florida Audubon Society, he funded a bird warden through the National Association of Audubon Societies. Fred Schultz was on duty by early spring 1934, a role he served for 29 years.

Originally called the “Tampa Bay Sanctuaries,” the name was changed to “Florida Coastal Islands Sanctuaries” in the late 1990s to include work outside of Tampa Bay. This year, FCIS staff and volunteers worked in concert to post, patrol and manage bird habitat on 29 islands, from St. Joseph Sound in northern Pinellas County to White Pelican Island in northern Charlotte County, mostly in protected bays and estuaries. FCIS also collaborated with the agencies responsible for nesting sites at another 46 colonies in the region, conducting surveys and assisting with management issues.

Over 53,000 pairs of colonial waterbirds of 30 species, including some of Florida’s rarest birds (gull-billed terns, roseate spoonbills, reddish egrets, American oystercatchers) and some of our most iconic (brown pelicans and great egrets) nested regionally this year. FCIS managed about 20% of the islands where they nested, plus assisted agencies, companies and private individuals responsible for managing other bird habitat islands, for a total of nearly 90% of the regionally nesting colonial waterbirds.

Habitat management has included a broad range of initiatives. We have been monitoring installed breakwater projects at the Alafia Bank Bird Sanctuary as required by the permitting agencies while also seeking additional funding and developing the engineering plans and permits to add more erosion control/oyster habitat. We continue our successional vegetation control efforts at Port Manatee’s Manbirtee Key to facilitate beach-nesting bird (terns and plovers) colonies on top of the spoil dike. The mangrove thicket on the southeast side hosted a small heronry for the past three years. We surveyed oystercatchers across the region to determine if nesting was successful and to assess productivity.

Seasonal activities included weekend and holiday patrols in Hillsborough Bay and daily monitoring of dredge material placement on spoil islands by the Army Corps of Engineers to ensure that nesting birds were not impacted. And for the 20th year in a row, we coordinated the Tampa Bay Fishing Line Cleanup with Tampa Bay Watch, where 50 boat captains and their crews removed dangerous line from nesting and foraging island habitats in Tampa Bay.

[su_divider]Tampa Bay Watch Celebrates 20 Years of Community-Based Habitat Restoration & Education

By Rachel Arndt, communications coordinator

Tampa Bay Watch has come a long way since a small group of bay managers and community volunteers founded the organization 20 years ago.

Through the decades, oyster reef restoration has been an important focus for TBW. Since 2001, 2,841 volunteers committed 9,364 hours to installing 694 tons of shell that created 8,267 feet of reef. Since 2000, over 11,000 oyster domes have been built and installed in Tampa Bay. More than 8,000 were installed at MacDill Air Force Base in a comprehensive shoreline stabilization project to help reduce nearshore wave energy and provide critical habitat for fish and wildlife.

Tampa Bay Watch conducts derelict crab trap removals two times throughout the year: in the winter months to coincide with the extreme low tides for easiest identification of traps and during the semi-annual closure of the blue crab fishery that occurs in July of odd numbered years (See Bay Soundings, Fall 2004). Each event is coordinated with the Florida Fish and Wildlife Commission as well as the Florida Airboat Association which provides airboats during the winter events that allow access to shallow waters. More than 1,200 “ghost traps” have been removed since 2007 in 25 events.

Tampa Bay is one of the only estuaries in the nation to have seen significant water quality improvements due in part to the efforts of community habitat restoration projects. A great strength of Tampa Bay Watch is the support the organization receives from the community. Personal experience with nature builds the desire to protect nature, which is why we offer multiple opportunities for residents of all ages to experience the amazing Tampa Bay.

[su_divider]

Tampa Port Authority Completes Restoration Project

Projects that mitigate for two new berths at Port Tampa Bay have made one of the bay’s most developed segments friendlier for wildlife.

Three major initiatives – completed in a partnership between the Tampa Port Authority, the Southwest Florida Water Management District’s SWIM (Surface Water Improvement & Management) program and the Florida Department of Transportation – have created 19 acres of wetlands, filled a 56-acre dredge hole and restored 50 acres of shoreline by removing invasive plants, creating intertidal pools and restoring freshwater uplands.

The dredge hole, identified as having the poorest habitat quality in Tampa Bay, required the equivalent of two football stadiums full of fill material. Dredging the berths and then creating the wetlands provided more than 300,000 cubic yards of fill for the project. Even in its degraded state, McKay Bay attracted a large number of birds. Wildlife, including the spectacular roseate spoonbill, began moving into restored habitat even as work continued nearby.

[su_divider]Water Atlas Provides Detailed Data on Water Quality in Region

The State of the Bay is much easier to track using the Water Atlas, an online resource that compiles water quality data from across the region. Developed by the Florida Center for Design + Research at the University of South Florida, the Water Alas includes both historic information and real-time data on water quality in Hillsborough, Pinellas, Manatee and Sarasota counties as well as Polk, Lake, Orange and Seminole.

A recent addition to coastal Water Atlases is a new webpage with the results of tidal stream assessments performed for National Estuary Programs in Tampa Bay, Sarasota and Charlotte Harbor. Water quality in estuaries is affected by tidal streams, which carry sediments and pollutants from coastal watersheds. The assessments were performed as part of a larger project funded by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency that studied nutrient regimes of tidal creeks prior to developing appropriate regulatory criteria for them.

Another new project being developed by the Water Atlas staff is a metadata catalog which will have information about all water monitoring going on in the state of Florida. The “Water-Cat” – or Catalog of Florida Monitoring Programs – is coordinated by the Florida Water Resources Monitoring Council, a network of stakeholders from many disciplines and organizations that participate in water resource monitoring and management. The website is scheduled to be completed by Fall 2014.

Learn more at www.wateratlas.usf.edu.

[su_divider]